The object-rich world is crucial for making systemic games. Similarly, the state-space of your game can be used to describe the entirety of your design and to facilitate more holistic game development.

But it’s about time that we talked about data, since it keeps coming up. How to describe the smallest pieces of your simulation and the effects of this choice on your game.

This nicely rounds out the design space for systemic games.

State and Context

One of the key things I have long wanted to solve is how to handle data as an external element to a project to facilitate both modularity and extensibility. The engine will have to interface with the data, but you shouldn’t have to chase down specific objects in a level to modify them.

To better understand why this matters, let’s establish some terminology.

Data

We’ve defined data as almost everything a computer is operating on, and something we tend to bundle up and package as content using various tools. At this level, all data is more or less the same.

- Everything in a game is data.

- Data is often bundled up as content.

State

A person’s state of being or state of mind define data in the moment: how you are right now and what you are thinking about or feeling. In computer science, state is remembered data; things that are stored and can be referenced.

- State is data that is stored and can be referenced.

- Something’s ‘state’ is its value when checked in the moment.

Context

Context, in computing, is the minimum amount of state that needs to be saved to be able to restore the same state at a later point (where “context-switching” comes from). But for this post’s purposes, it’s more literal.

The local context is an object’s local state at a given moment in the simulation.

- Local context is an object’s local state at a given moment.

Once we start introducing more objects to the simulation, their relationships will result in relative context: object-relative state in a given moment. Comparisons expressed as state. For example, whether one object is moving faster or slower than another.

- Relative context is an object’s state in comparison to other objects.

State Properties

When you plan out your state, it’s also relevant to consider how and by who it will be used. If you change a value that only exists for a single-player game it’s probably fine to treat it more carelessly. If players decide to go in and change it, this will not amount to cheating since it’ll only change their local gameplay experience. It’ll functionally be modding.

But if you are building a multiplayer game with server-side authority and a network backend, you need to make different considerations and plan your data much more carefully.

- Hard-coded. Data is “hard-coded” when it’s written directly into program code and compiled, making it impossible to iterate on the data while the game is running and complicating knowledge sharing and tweaking. Initial test data, like move speeds or jump heights, can sometimes be hard-coded to make sure something works.

- Constant. A named variable that is available throughout a given scope. Pi and the gravitational constant, or your game’s easy mode damage baseline (see later) can be constants.

- Variable. A variable is a name for data that changes at runtime, or at least can change at runtime. Move speeds, jump heights, and other classics are examples of variables that may be manipulated during play.

- Tweakable. A number that developers can access readily and that may need several rounds of tweaking. This type of number benefits from templating (see later) and from being externalized from the object(s) it is affecting. Individual values for long lists of items, like the Damage value for all of your 250 guns, or the gold costs for your 1,000 items.

- Metric. A metric is something that gets sent to a backend and can be used to analyze how players engage with your game. It’s rarely a variable or even a tweakable that gets sent this way. May be something as simple as telling the backend which level is started or the duration of a challenge the player played.

- Optional. This is data, typically a variable, that is accessed directly by the player. The font scale, color of the UI, music volume, etc.; but it can also go deeper, as with the many customization options you have in a game like Civilization.

- Persistent. Data is ‘persistent’ when it needs to live across multiple game sessions. You don’t need to make constants persistent, for example, or really anything that is represented by content, but anything that should stay the same between play sessions will have to be persistent. Current health, current level, location of character in the game world, optional settings (like volume), etc., will usually be expected to be persistent.

- Visible. Whether a number or other point of data is player-facing is a crucial consideration. Anything that is player-facing will usually require filtering (e.g., Imperial vs Metric, or other localization), and needs to be more carefully designed than data that only exists in the simulation. Damage and health numbers, character names, dialogue subtitles, etc.

- Content. Usually when a game is referred to as data-driven, it’s because files on disk are defining how things get set up. Tweaking this data is about changing it, sometimes through an external tool or suite of tools. A premade level, an enemy with all its key data assigned through a registry file, or a 3D asset.

- Global. Data that is accessible everywhere in the game is global. This is generally the only scope consideration you need to do when you are designing your state space, since individual scopes are not as relevant or even automatic to the context you are working in. Quest facts, like if you have met Character Y before can be global, and optional and player-facing data is often global.

- Input. Data that comes from hardware input is a bit different, since you rarely want your game to access it directly. Rather, it’s good practice to use some kind of abstraction between the input and the gameplay action triggered by it. Analogue X/Y stick movement axes, touch gesture events, button presses and releases, etc.

- Replicated. Data that gets sent to clients across a network to simulate the same game state is said to be replicated. Which data a game replicates is an extremely important design consideration for multiplayer games and is therefore an important property to consider. Input sent to a server, timed events sent across peers in peer-to-peer networking, etc.

- Fuzzified. Data sets that has variable degrees of membership are referred to as “fuzzified” data, and we get into that later in this post. It’s a technique that can be used to turn tricky numbers into human-readable form and to allow computers to communicate in a way that somewhat resembles human conversation. How ‘warm’ a temperature is, how ‘damaged’ a character is, etc.

- Partial. If merely to track connections between pieces of data, it can be relevant to flag something as only part of a larger whole. If you separate data into base, attribute, and modifier, for example, noting that the data is partial and how can be very relevant. Any data that needs other data to be functional; maybe Strength is added to Damage and then multiplied by HitLocation; these three are then all partial pieces of data from the damage function.

- Temporary. Data that has a start and end time during the simulation and that isn’t technically variables. They can still be parts of key functions, but are not something that the developer is actively tweaking. Match points that are tossed out after tallying, score multipliers that are accumulated for just a single second, etc.

State Representation

All games represent state in some way, even if we may not think of it or plan it as such. There will be health numbers, speeds, and all manner of things to represent, and sometimes this grows organically from implementing the features we want.

“Eh,” the designer says to the programmer, “we need to add a Headshot Damage Multiplier to each enemy now that we have the helmeted one.” Additional state gets added, and often to every single object in the game, and not just to the ones that need it.

How we represent this state in our logic is what this section is about. It can be just a flat number in a spreadsheet somewhere; what Michael Sellers would call the “spreadsheet specific” layer of your data. But it can also use one of many existing ways for easy or efficient data representation.

Conceptual Separation

When you work with numbers in games the only thing that is certain is uncertainty. You will change the numbers down the line. But the great risk of any numeric system that changes it that you get cascading effects if you don’t plan for which levers you need beforehand.

To do this, you can separate the numbers up front into Baseline, Attributes, Modifiers, and Functions. You can read more about this in a previous post on gamification.

Spreadsheet Specific

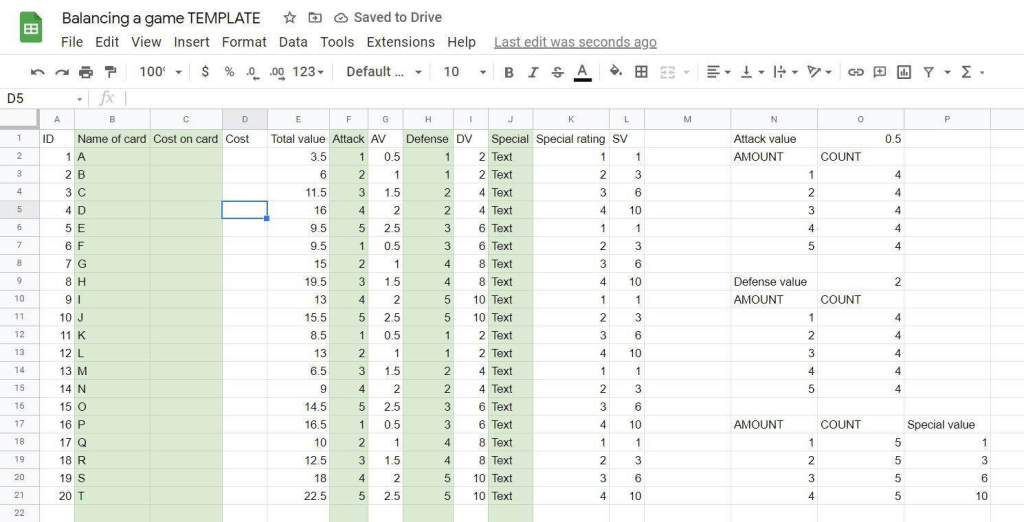

King Arthur may have his Excalibur; as system designers we wield Excel! For many game designers it’s natural to gravitate towards spreadsheet tools for data management. To separate things into rows and columns and make any relevant changes as needed.

Because of this, you will find variations on spreadsheet support for most game engines. It’s quite common to use the comma-separated values (CSV) format to export them from spreadsheets and pull them directly into your game engine.

I use spreadsheets for a lot of things but very rarely for direct authoring of data. This is a preference, of course, but also comes from how spreadsheets represent data. Since it’s natural to simply add another column to represent a new feature for an object, even if it means that there’ll be an additional “0” in that column for every object that doesn’t use it. The risk for bloat is very high.

Some of the procedural implementations of features described in the post on building a systemic gun come from a spreadsheet specific line of thinking and is far more common than you’d expect.

XML

The Extensible Markup Language (XML) is sometimes used for registry files that can be compiled into game data, and sometimes in portable formats where the XML remains accessible for developers or players to change the values if they want. Variants of XML were extremely common in the past but is something I haven’t personally seen as much in recent years except in its XAML format for UI construction.

XML has a very readable and extensible format, with tags and closing tags that tell the parser what to expect. It can also be generated easily using custom tools.

<gameobject type="Character">

<name>Goblin</name>

<class>Fighter</class>

<str>10</str>

<hp>4</hp>

<equipment>

<item>Dagger</item>

<item>Letter to home</item>

</equipment>

</gameobject>JSON

Probably more common today than XML, the JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) has pretty much the same benefits but is maybe slightly more readable. Which one you prefer, if any, is mostly down to preferences.

JSON is used extensively in web development and database formats, which is probably one of the reasons it’s become more and more common.

{

"type": "Character",

"name": "Goblin",

"str": 10,

"hp": 4,

"equipment": [

"Dagger",

"Letter to home"

]

}Lookup Tables

A lookup table is an array that contains all potential instances of some piece of data and allows it to be referenced by index. In any situation where you end up copying the same data over and over, potentially into hundreds or even thousands of instances of identical values, this can be a big way to save yourself from headaches (and memory waste).

Imagine a flow field, for example. A space that represents the vector force you’d apply to any unit walking a grid based on which grid cell it’s currently occupying. This could have each cell use its own Vector3D, with three separate floating point numbers per cell, or it could store a single byte with a lookup table index. The Vector3Ds would only be stored in a single place. This shrinks the amount of data you need to use by a lot and makes it easier to plan the data from a design perspective.

Since many types of state will repeat, lookup tables are a good way to represent them and can also provide a single location for developers to tweak values. For example, the damage modifier added from difficulty could live in a difficulty lookup table.

Array<Vector3D> FlowfieldVectors =

{

Vector3D::Zero, // 0

Vector3D::Up, // 1

Vector3D::Down, // 2

Vector3D::Left, // 3

Vector3D::Right, // 4

Vector3D::Normalize(Vector3D::Up + Vector3D::Right), // 5

Vector3D::Normalize(Vector3D::Up + Vector3D::Left), // 6

Vector3D::Normalize(Vector3D::Down + Vector3D::Right), // 7

Vector3D::Normalize(Vector3D::Down + Vector3D::Left), // 8

};Scripting Language

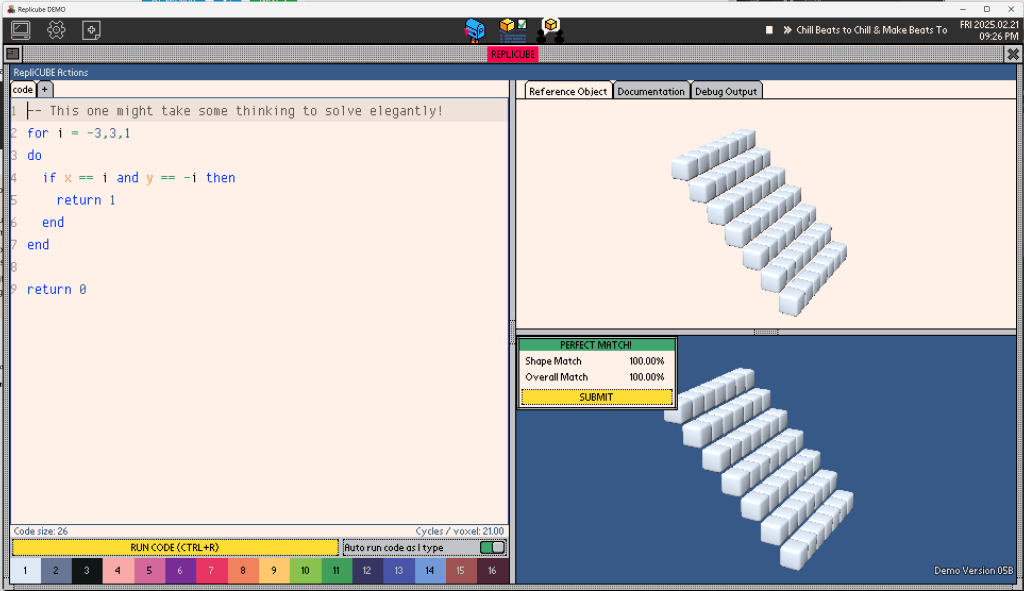

If you want more than just object representation in a serialised format, a good way to achieve it is by using an external scripting language. Where spreadsheets and object notation allow you to populate your game with data, a scripting language allows you to provide logic along with the data.

The below example is taken from the excellent book Programming Game AI by Example, by Mat Buckland, and shows a small Lua script defining a state (State_GoHome) for a state machine. A good example of what you can turn into data-driven parts of your game with a scripting language.

This is often within the realm of what a technical designer would be working with, since it allows behavior to be constructed outside the compiled game client and therefore makes iteration a lot faster.

State_GoHome = {}

State_GoHome["Enter"] = function(miner)

print ("Walkin home in the hot n' thusty heat of the desert")

end

State_GoHome["Execute"] = function(miner)

print ("Back at the shack. yer siree!")

if miner:Fatigued() then

miner:GetFSM():ChangeState(State_Sleep)

else

miner:GetFSM():ChangeState(State_GoToMine)

end

end

State_GoHome["Exit"] = function(miner)

print ("Puttin' mah boots on n' gettin' ready for a day at the mine")

endIf you push it even further, you can even make the scripting language a player-facing element, but then you’re obviously going into a different realm than data handling.

Key-Value Pairs

Context the way I refer to it in this post is inspired by Elan Ruskin’s approach to dialog on Left 4 Dead. In his own words (from the book Procedural Storytelling in Games), “A context is a single key-value pair such as PlayerHealth:72 or CurrentMap:Village5. For performance reasons it’s best to use numeric values as much as possible, so for string values such as names, consider internally replacing then with unique symbols or hashes.”

A key-value pair can be represented in many different ways in code and is often used in data structures like maps and dictionaries. You’ve probably already made use of them many times before.

template <typename KEY, typename VALUE>

struct KeyValuePair

{

KEY key;

VALUE value;

};World Properties

Inspired by Jeff Orkin’s world state representation, one way you can represent state is by using a union in C++ or explicit memory layout in C#. Each piece of state will always take up the same amount of memory, you can pool it easily, and you can use it across your game to describe the state of individual objects.

In the case of Goal-Oriented Action Planning (GOAP), this state is used to represent the current setup of the world so that enemy AI can make up a plan to execute. The state is handled as nodes in a graph with the edges represent actions. A goal-first A* algorithm handles the planning.

This way of representing runtime state has other benefits too. One of them is that it can be decoupled from the objects that the data represents and can then be used for other intermediary operations as well.

How it looks in the paper:

struct SWorldProperty

{

GAME_OBJECT_ID hSubjectID;

WORLD_PROP_KEY eKey;

union value

{

bool bValue;

float fValue;

int nValue;

...

};

};And here is how the paper demonstrates the use of a world property:

SWorldProperty Prop;

Prop.hSubjectID = hShooterID;

Prop.eKey = kTargetIsDead;

Prop.bValue = true; “If the planner is trying to satisfy the KillEnemy goal,” writes Jeff Orkin, “it does not need to know the shooter’s health, current location, or anything else. The planner does not even need to know whom the shooter is trying to kill! It just needs to find a sequence of actions that will lead to this shooter’s target getting killed, whomever that target may be.”

In other words, it’s enough to store exactly what you need right now as world properties, and not treat game state as a runtime database.

Tags

Tags have a lot in common with keywords in card and board game design. It’s the use of a single word or few-word sentence as shorthand for a game rule or exception. Some creatures in Magic: The Gathering deal their damage before other creatures get to deal theirs, for example. A rule effect referred to consistently as “First strike.”

This same principle can be applied to game state too. As a descriptor (“Elf”), for conditional reasons (“Immunity.Fire”), or as a modifier (“Burning”). Consider a concept such as damage types for example. Just a damage number is fine, but you may want to qualify certain types of damage. Maybe a Piercing weapon does less damage to skeletons, or is better protected against by a chainmail armor. Then Piercing can be a tag applied to all three: weapons, enemies, and armor.

Most game engines use tags in one way or another. They may be developer-facing strings that get hashed at compile-time or they can be sent as a stream. Some engines do none of this automatically, however, and may expect you as the developer to not do unnecessary string comparisons or other expensive things at runtime. (As a general rule you should always avoid comparing strings to each other: compare their hash, length, or other cheaper thing instead.)

struct Tag

{

// A hash of the original string, used for fast comparisons.

int32 Hash;

// An index into a single array where all the strings can be found.

#ifdef _DEBUG

int32 StringIndex;

#endif

};With a tag specified, and the developer-facing strings present somewhere, you can then create a structure for comparing groups of tags against each other and to test if specific tags are present. Of course, you may want to make the strings player-facing too and expose it completely to the game, but that’s not a requirement.

struct TagCollection

{

Array<Tag> Tags;

void AddTags(Array<Tag>& NewTags);

// Has this specific tag.

bool HasTag(Tag& Tag);

// Has any of the tags in the other collection.

bool Any(TagCollection* Other);

// Has all of the tags in the other collection.

bool All(TagCollection* Other);

// Has exactly the same tags as another collection.

bool Exact(TagCollection* Other);

};Maybe you want to do additive trait-matching, and check if an armor has Resistance.Piercing before you deal damage with a sword that has Damage.Piercing. Or you want to collect tags as context before you do fuzzy pattern-matching.

Simply put: tags are extremely useful.

Data Assets and Fuzzy Sets

Many struggle to remember the exact number 9.80665. But if we refer to it as Gravity we don’t have to use the number. We can also change it down the line in a single place if we suddenly want things to behave differently across our game. When we do this, we fuzzify the data. We use words to describe it, as with variables in code.

This can be done in a template (or C# generic), for example:

template <typename T>

class DataAsset

{

T value;

public:

DataAsset(T new_value) : value(new_value) {}

T GetValue() const { return value; }

void SetValue(T new_value) { value = new_value; }

// Serialization and other fun stuff!

};With a template like this, you can easily add saving and loading, comparison checks, and other handy ways of reusing the concept of data across your game. It’ll all just be added to the DataAsset class and you can make all of them live in a single place in memory, on disk, or whatever you want.

DataAsset<float> Gravity = DataAsset<float>(9.80665f);It’s straightforward to use, even if this variant would still rely on hard-coded numbers, and it’s generally a better idea to use external JSON or other scripting methods that can be changed without having to recompile your code.

The real power of fuzzification is that you can start referring to numbers conceptually and not just as plain numbers. This doesn’t just simplify the conversation, it also means you don’t have to painstakingly change that price point for a gazillion individual items.

struct Prices

{

DataAsset<int> cheap = DataAsset<int>(5);

DataAsset<int> ok = DataAsset<int>(150);

DataAsset<int> costly = DataAsset<int>(2200);

DataAsset<int> expensive = DataAsset<int>(17000);

};This same principle can be applied to sets with more than just one point of data. We will then want to define fuzzy sets where your input will have a degree of membership with each value in the set.

struct FuzzyKeyValue

{

float key;

float value;

FuzzyKeyValue(float _key, float _value)

{ key = _key; value = _value; }

};

template <typename T>

class FuzzySet

{

T object;

Array<FuzzyKeyValue> keys;

public:

FuzzySet(T _object, Array<FuzzyKeyValue> _keys)

{

object = _object;

keys = _keys;

}

T GetObject() { return object; }

float Evaluate(float t)

{

// Assert that there are at least two keys; pointless if not

for(auto i = 1; i < Keys.Num(); i++)

{

auto a = Keys[i-1];

auto b = Keys[i];

if(t >= a.Key && t <= b.Key)

{

// Return the 'degree of membership' of the supplied t

return Lerp(a.Value, b.Value, (t-a.Key) / (b.Key-a.Key));

}

}

}

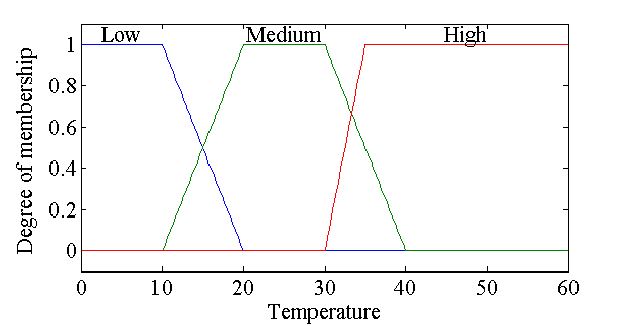

};Let’s grab an example of something fuzzified from the Internet. In this case temperature:

To represent this in the simple code from before, it’d look something like this:

// Low

keys_low = {

new FuzzyKeyValue(1f, 0),

new FuzzyKeyValue(1f, 10),

new FuzzyKeyValue(0f, 20)

};

FuzzySet<string>("Low", keys_low);

// Medium

keys_medium = {

new FuzzyKeyValue(0f, 10),

new FuzzyKeyValue(1f, 20),

new FuzzyKeyValue(1f, 30),

new FuzzyKeyValue(0f, 40),

};

FuzzySet<string>("Medium", keys_medium);

// High

keys_high = {

new FuzzyKeyValue(0f, 30),

new FuzzyKeyValue(1f, 35),

new FuzzyKeyValue(1f, 60)

};

FuzzySet<string>("High", keys_high);To finally make practical use of this data, we can wrap a number of sets together, like the example below, to find out how warm a certain temperature is.

struct FuzzyTemperature

{

FuzzySet<string>[] Temperatures =

{

FuzzySet<string>("Low", keys_low),

FuzzySet<string>("Medium", keys_medium),

FuzzySet<string>("High", keys_high)

};

string Evaluate(float t)

{

string returnString = "";

auto evaluation = 0.f;

for(auto set : Temperatures)

{

auto eval = set.Evaluate(t);

if(eval > evaluation)

{

evaluation = eval;

returnString = set.GetObject();

}

}

return returnString;

}

};Predicate functions

A predicate function is a function that returns a single boolean true or false from supplied parameters. It’s an excellent way to test the validity of different situations at runtime and graduates state into its relational equivalent, which we can call context.

Many world property unions will effectively do the same thing, such as the kTargetIsDead property example illustrating a desire for the target to be dead. A predicate function is where we learn what is true at runtime.

This can be simple and effectively reusable, for example if you have a resource object that can be reused for any number of resources:

bool ResourceCheck::ResourceBelowThreshold(const float Threshold) const

{

return PlayerData.ResourcePercentage < Threshold;

}Since predicates can be used for almost anything it can make a lot of sense to keep a bunch of them around in a gameplay-scope helper library. For the following examples, I was a bit lazy, but you can see how quickly this becomes useful. For example, if InFront and FacingSame are both true at the same time, it would be the contextual requirements for a classic video game stealth takedown.

static bool InFront(Transform* Self, Vector& TargetLocation)

{

return Self->InverseTransformPosition(TargetLocation).Z > 0.f;

}

static bool Behind(Transform* Self, Vector& TargetLocation)

{

return Self->InverseTransformPosition(TargetLocation).Z < 0.f;

}

static bool Left(Transform* Self, Vector& TargetLocation)

{

return Self->InverseTransformPosition(TargetLocation).X < 0.f;

}

static bool Right(Transform* Self, Vector& TargetLocation)

{

return Self->InverseTransformPosition(TargetLocation).X > 0.f;

}

static bool FacingSame(Transform* Self, Transform* Target)

{

auto FacingDot = Vector::Dot(Self->Forward(), Target->Forward());

return FacingDot > .9f;

}Once you have these helper functions, you can use them in code to generate tags, populate bitmasks or lookup tables, or determine what happens when objects hit each other. You can use them to generate context queries for dialogue or to qualify gameplay interactions.

Bitmasks

A bitmask means using a variable’s individual memory bits as flags. With a byte, you can store 8 bits. With a 32-bit integer, you can surprisingly enough store 32 bits. Many tutorials you’ll find will become shock-full of boolean flags faster than you can blink. A “bool,” though it stores the equivalent of a bit, is still one byte of memory due to the smallest addressable thing in memory having that size. A bitmask is therefore a way to not fill your memory with unnecessary waste while only recording bits anyway.

For the purposes of data, it’s also a convenient way to bundle related information together. A good example is spawn points and spawning in general. If you have, say, five different game modes and you want to be able to support all five using different spawn points, you can use a bitmask to store this information for each spawn point.

enum GameMode

{

assassinate = 1 << 1,

infiltrate = 1 << 2,

steal = 1 << 3,

defend = 1 << 4,

horde = 1 << 5

};

int32 CurrentState = assassinate | infiltrate | steal;

// Set a bit

CurrentState |= 1 << defend;

// Clear a bit

CurrentState &= ~(1 << defend);

// Toggle a bit

CurrentState ^= 1 << defend;

if((CurrentState & GameMode.assassinate) == GameMode.assassinate)

{

// 'assassinate' mode is supported.

}Asset Data

Last, but certainly not least, there are many ingenious ways to use asset data to store information. I will mention just a few, to give you some pointers, but suffice it to say that one reason technical artists are in high demand is that clever solutions to pipeline problems can save considerable amounts of time and money even for small projects.

The same principles can be used in many different ways to store systemic data and state.

Keyframes

Animation keyframes are used to store the positions, rotations, and scales of bones that are weighted to skinned meshes. This doesn’t have to be an animated character but can just as easily be a piece of cloth or parchment, or even a whole level.

The latter was a way for Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver to represent the two different worlds that the player could shift between. One keyframe per world (out of two).

Vertex Colors

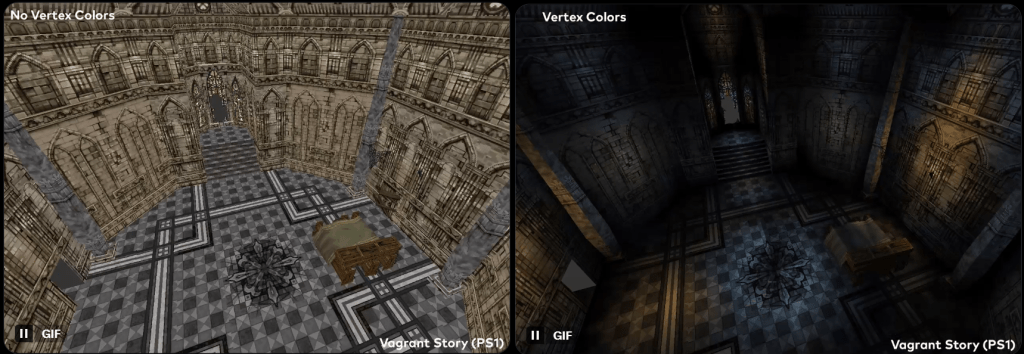

Using vertex colors to paint objects is tried and true, but when you texture your objects you may no longer need it for this purpose. This opens up countless other opportunities to store data in your mesh objects. For example, Vagrant Story used vertex colors to store its baked lighting. A technique that worked quite well at the resolutions for that game.

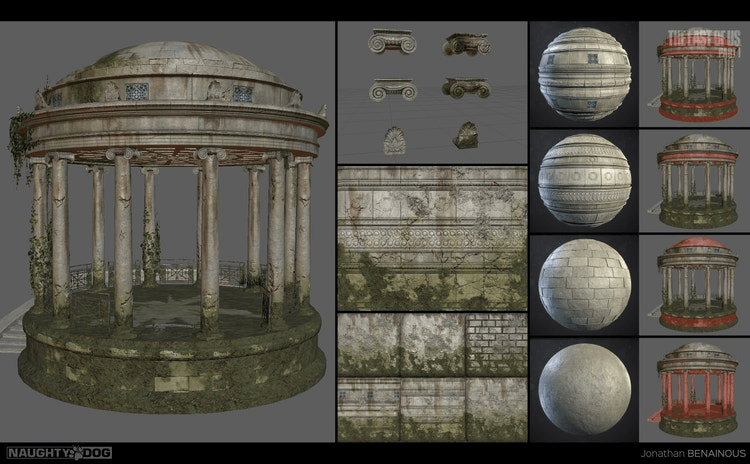

Most game engines have support for one full RGB vertex color per vertex. It’s possible to store more than one vertex color per vertex too, such as is the case in The Last of Us Part 1, where the different vertex color channels are used as mask values for things like mould, dirt, and cracks.

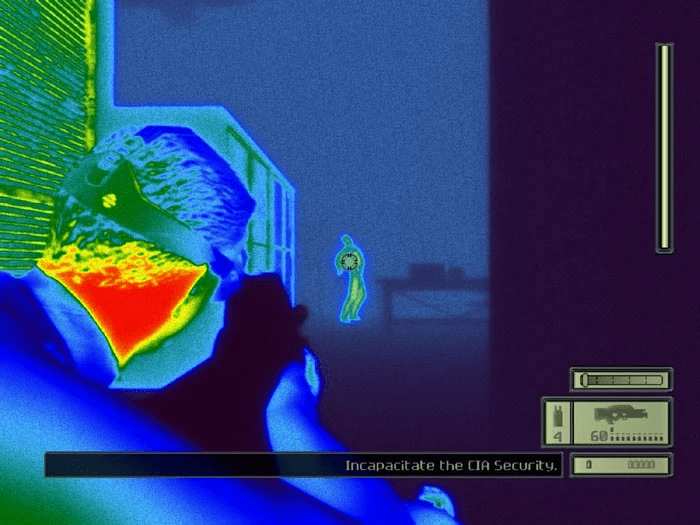

Furthermore, vertex colors can be accessed at runtime as well, and can then be used for updated live information. Say, the heat or magnetism generated by an object. I don’t know that this is how Splinter Cell does its heat vision, but it could be.

U-Dimensions

Something that has been mentioned before is how Neon Giant used the “U-dimension” (UDim) workflow not as a means to map more textures to an object but as a way to create masks simply by the act of UV-mapping a mesh.

This technique is quite clever and relies on mesh UVs (which are simply coordinates; “XY” was taken) using normalised values as a standard. I.e., values between 0 and 1. So by storing coordinates at higher values, like 1-2 or 2-3, you can map more than one set of UVs to the same object.

You can use this for anything where you’d use a mask or map more than one texture to the same object. It could be the albedo and metallic of a PBR material, as for Neon Giant, or you could map it to other properties such as bounciness or Resistance.Piercing.

Which One?

When you pick which way to represent your data, you need to consider four factors:

- Which tools pipeline you are already familiar with. Using UDims and other mesh techniques only make sense if you feel at home in a 3D suite, working with meshes. Similarly, you should only use CSVs and spreadsheets if you’re already comfortable with them or want to learn.

- Which problems you are solving. If your game is tied to a backend, JSON makes a lot of practical sense since it’s already speaking the language of the web. But if you want players to customize your game, it may make more sense to use a scripting language.

- Which levers you will need for testing and balancing. This is the most important, and the one that requires most design and planning. If you need to go back to an external tool every time something must be changed, whether that’s Excel or Blender, some changes may become too cumbersome to test.

- How the data will be communicated. Both internally, between objects in your game, and towards the player. Some things will be developer-facing only, others will be player-facing. Making sure to have one source of truth is extremely important.

Hopefully those pointers can help you at least consider how to represent your data. There are many ways that these things are tied together ultimately. Objects, data, state-spaces, etc., and there are more ways than can ever be summarised in a post like this.

I will come back to this post to extend it when new things crop up. So if you have any suggestions for clever data representations, please send them to annander@gmail.com and I’ll consider adding them along with a thank you.

2 thoughts on “A State-Rich Simulation”