Some time back, I plunged headfirst into the rabbit hole that is systemic game design. It’s turned out to be what I’ve been looking for my whole career and I feel like an idiot for not having discovered it as clearly much earlier.

Under this banner, I’ve already covered the First–Person 3Cs, how to make guns, and the conceptual relationships we can construct between objects. I’ve also talked about what a system is.

But what can a system do?

There’s of course no simple or consistent way to define what systems can do, so instead of trying to define it, I’ll give you a bunch of practical examples.

Manipulation

The first thing I’ll mention is the types of object relationships covered in the last article. Imagine an effect of any kind: damage, fire, dialogue speech, explisions; anything. We can call them properties, just to have something to refer to. An object is then something that has properties.

A property in this model describes how an interaction is allowed to happen. Each property is a kind of interface defining how the object can be manipulated but leaving the implementation of this manipulation to the object itself. For example, a steel door with the Flammable property may heat up and turn red, while a wooden door with the Flammable property catches fire. The same interface (“Flammable”) is responsible for this, but the respective doors have their own functional implementations.

What happens in the simulation is mostly about the relationships between objects as defined by their properties. In other words, how and when these interfaces are triggered. We’ll refer to this as manipulation of properties.

Add

The activity of adding properties to objects. Say, adding the Flammable property to an object because you doused it in gasoline, or maybe adding Shatterable because you froze it solid. Adding properties may fundamentally alter an object’s behavior and appearance.

Remove

Of course, dousing a flammable object in water may remove Flammable from it, and heating it may melt the ice and remove Shatterable. Removing is the opposite of adding, naturally, and will affect behavior and appearance accordingly.

Verify

You will often want to know if an object has a certain property. Sometimes to qualify addition or removal, for example checking if an object can ever be flammable before making it so. At other times, this can tie into AI behaviours or other functions that can trigger reactions. For example, if you see something flammable you may want to set it on fire. Verification can be as simple as line of sight or as complicated as a deep dynamic dialogue tree or utility system.

Obfuscate

The opposite of verifying something is to obfuscate it. This is less obvious, but if something needs line of sight to verify then obfuscation is what will make sure said line of sight never happens. The desirable state of not allowing things to be verified. Codename 47 donning a chef’s hat, or a Prey mimic pretending to be a chair are examples of obfuscation of properties.

Creation

Manipulating properties is the heart of this whole thing, but things must be created before they can be manipulated, so we’ll go on a quick sidequest into the land of object creation.

In games we tend to speak of spawning things and then despawning them once they’re dead or have done their thing. This applies to both objects and properties, but when we speak of spawning it’s usually objects we’re talking about.

One thing that’s conceptually important is that you shouldn’t put objects directly into your level–you should use some kind of abstraction for them, and let runtime systems spawn them for you as needed. In other words, you should separate the concept of a spawner from its spawn points. The first is usually in the realm of programming and the second in the realm of level design.

Spawners

This is the system side of your game’s object creation. It needs to keep track of currently spawned objects, spawn new ones as needed, respect the rules of spawning set up by the game’s designers, and may also communicate information to spawned objects. For example, where the player is located, or which specific spawn points are currently unavailable because of player proximity.

For the first-person games I’ve worked on, it’s rarely been very complicated. Spawn points are placed as objects in a level and the spawning is triggered from a script, usually a trigger box or door. The spawner’s only “job” will then be to allocate and deallocate memory the spawned enemy needs and to keep track of shared resources like the pathfinder in use or the level’s navmesh.

It will also manage global restrictions like the maximum number of enemies that are allowed to spawn at any given moment.

Wave Spawners

A popular way to spawn things in action games is to do so in waves. Think of the Gears of War horde mode, or Halo 3: O.D.S.T.‘s Firefight. A wave can be given a budget that is spent per wave, and then each wave gets a larger budget. Or it can be predefined exactly which enemies are combined into which wave.

To illustrate what I mean with a budget, picture that a wave gets 100 points to “spend” on spawns. Spawning one shootery enemy with a handgun may cost 5 points from that budget, while a rocket launcher enemy might cost 15 points. You would then randomise spawns until the 100 points has been spent or the lowest cost is too high for the remaining budget–then you have your wave defined and you send it to the spawner. Budget-based spawning can also provide room for rewards, for example by having them add more points to the budget. So if you spawn a rocket launcher the players can pick up, this may add another +10 points to the spawning budget.

Do note that budget-based spawning is just an example. As you can imagine, there are countless ways to generate a list of obects to spawn.

Regardless of where the list is coming from, spawning system will make use of the spawn points available, usually by spawning new waves completely at random or as far away from the players as possible, and once a predetermined number of waves has been survived the level ends and you get some score. Or it just keeps going until you die, Geometry Wars-style.

Directors

A director is an entity that keeps track of global game state, like the number of enemies spawned, total health of players, and whatever other data it may need. It also has access to all the spawners in your system and can make use of them as it sees fit.

You can liken a director to a game AI. But unlike enemy AI, it’s not geared for animating, moving and playing sounds, but to create objects and maintain a certain level of pacing. This means you can absolutely have state machines, behavior trees, planners, or utility systems that determine how and when something should spawn. You can go as far down this rabbit hole as time permits.

A primitive way to implement a director is to use the same type of budget mentioned before, but combine this with a curve or function that caps the budget dynamically. You can then affect this curve when players take damage or die, or when players defeat a boss, and you scale the spawning budget accordingly to create ups and downs in the game’s pacing.

Another interesting way is to use a metronome and pace the beat based on how you want the game to feel at certain points. A line of thinking that ties the pace of a game to music the same way some film makers like to think of dialogue.

Spawn Points

A spawn point is a typically hand-placed location in the game’s world space. It’ll usually have some qualifiers, like which game modes it’ll be active in or which missions it’s used for, but it’s really just a way to specify a location in world space.

Also remember that the spawn point itself is an object. In an ECS architecture, it’d be an Entity, and a SpawningSystem would be handling the spawning. In Unreal it’d usually be derived from AActor, and in Unity it’d be a GameObject with a MonoBehaviour doing spawny things.

Typical information you will have in a spawn point and allow designers to tweak:

- Transform. Location, rotation, scale. (It’s usually enough with location and facing direction, or location only, you rarely need a full transformation matrix.)

- Spawn Type. A class or object reference, potentially an array of references, that determines what should spawn at this spawn point.

- Some flags you can set, based on the behavior you want. If the spawner should destroy itself after activating, whether it should activate immediately as the game starts, etc. Your specific game will of course determine what kinds of flags you have.

- Radius. A radius within the spawn point inside of which the spawn will occur, usually at a randomly generated spot.

- Spawn Count. How many spawns can occur from this spawn point.

- Delay. How long you must wait after each spawn to have it trigger a new spawn.

class SpawnPoint : public Spawner<Entity*>

{

public:

Array<Entity*> EntityTemplates;

float Radius;

ESpawnFlags Flags = AutomaticSpawn | SpawnOnce;

void Spawn() override

{

FVector2D RandVector = Random.UnitCircle * Radius;

RandomPosition = SpawnerTransform.Position + FVector3D(RandVector .X, RandVector.Y, SpawnerTransform.Z);

SpawnEntity(RandomPosition );

};

void PostSpawn(Entity* SpawnedEntity) override

{

SpawnedEntity->SetForwardVector(SpawnerTransform.ForwardVector);

};

}Spawn Shapes

When you want to spawn multiple entities in a shape or volume, it’s handy to use a spawn shape of some kind. It’s really the same thing as a spawn point but it uses a more defined shape and not just a radius. Squares, cubes, even mesh shapes can be used for when you need very specific spawns to occur.

A common variant is the concept of a room. Say, a square spawner on the floor of the kitchen, or inside the elevator, and you can then refer to this as “kitchen” or “elevator” when you spawn enemies in your scripts instead of referring to the spawnpoints spawnpoint_321, spawnpoint_45, spawnpoint_932, and spawnpoint_322 (because, let’s face it, objects with automatic incrementation in naming are never grouped together).

Monster Closets

Spawning enemies into games where enemies have a short survival timer is extremely tricky. Some games simply don’t bother at all and have enemies spawn from the ground or out of thin air with a magical visual effect. Others use elaborate animations, like enemies rappelling down from the rooftops getting dropped off by dropships.

A “monster closet” is another alternative. A kind of one-way door that the player can’t enter at all, but that enemies can exit from. Not much more to it.

Spawn Trees

There are many algorithmic ways to generate branching structures, such as Lindenmayer systems, but here we’ll just provide a very primitive one that demonstrates the line of thinking.

Let’s say that you have a room, and inside this room you have furniture, and on the furniture there are props. These follow the same structure as a tree, with the room as the trunk, the furniture the branches, and the props as the leaves. The trunk has branch children, each branch can have leaf children, and leaves have no children at all. You may want to extend this so that branches can have their own branches and some leaf nodes may have multiple leaves. But all of the many permutations we’ll simply leave to your imagination.

Let’s just spec the three types lazily:

enum ETreeNodeType

{

Trunk,

Branch,

Leaf

};This enum is the only thing we’d need to identify something as a trunk, branch, or leaf (or room, furniture, and prop; or something else). We can make these assets on disk and then plug them in as candidates into the spawner itself. A spawner that is simply another version of the standard spawner we also used before.

We don’t necessarily need more than one room. That could just be a tile in a generator. But having a chair, table, treasure chest, and some other pieces of furniture to place could be nice. Then some leaves. Plates, candles, whatever you may want. A chair could also be a kind of leaf, that could only be added to a table for example. There are many different ways to approach these simple definitions.

struct Furniture : public TreeNode

{

ETreeNodeType NodeType = Branch;

};Finally, all the spawner really needs to do is call the Spawn method one layer at a time to populate first branches and then leaf nodes.

class TreeSpawner : public Spawner<TreeNode>

{

public:

Array<TreeNode*> NodeTemplates;

void Spawn() override

{

// Spawn the trunk instance

auto TrunkCandidate = GetRoomByType(TreeNodeType.Trunk);

Spawn(SpawnerTransform.Position);

}

void PostSpawn(TreeNode* Instance) override

{

// Collect all branches. Branches will do the same for leafs.

auto BranchNodes = GetChildren<TreeNode>();

for(auto Node : BranchNodes)

{

if (instance.NodeType == Node.NodeType)

{

continue;

}

else

{

auto NewInstance = GetRoomByType(Node.NodeType);

Spawn(Node.Position);

}

}

}

private TreeNode GetRoomByType(ETreeNodeType Type)

{

auto Candidates = Array<TreeNode*>();

for(auto Room : NodeTemplates)

{

if (Room.NodeType == Type)

Candidates.Add(Room);

}

if (Candidates.Num() > 0)

{

auto Index = Random::Range(0, Candidates.Num() - 1);

return Candidates[Index];

}

return nullptr;

}

}Spawn Groups

A spawn group is a predefined group of spawns that are always spawned together. It can be a squad with their leader, a boss with its entourage, or the bandits and the caravan they are currently raiding. A spawn group will often contain more logic than just who should spawn, such as sounds to play or animations to start from, but this isn’t necessary.

In a budget-based situation, a group of rocket launcher soldiers with a named leader could simply cost a set amount of points and then be handled as a unique spawn that can only happen once.

A spawn group can also be the specific set of enemeis allowed to spawn in a certain game mode. Maybe the patrolling stealth group, or the assaulting super-soldier group.

Off-Screen Spawners

Rather than using any manual spawn points or other work-intensive spawning models, you can simply find any location outside the viewport bounds or screen edges and spawn your enemies there.

For 3D games with simulated worlds, this may feel cheap if it’s not done carefully, but for most 2D games it’s tried and true.

Activation

We have objects in our scene now! But before we can manipulate them, we need ways to affect them at a higher level. Rotating what needs rotation, opening what needs opening; spawning what needs spawning.

The first way we do this is by listening to events at various stages of the game engine’s resource management. Object was created. Game level finished loading. Loading of new level was triggered. This ties directly into standard software engineering practices and the style of lifetime management we need to do for memory reasons anyway.

The second way is that we listen for changes in game state at runtime. When something is spotted by an AI, after a cutscene ends, an object is damaged by the combat system, or when an object in a physics simulation collides with another. These types of events can be varied. A collision can cause an effect as simple as pushing another object, or it can serve to propagate its properties to the colliding object.

Thirdly, we can use messages. Either as general broadcasts to everyone everywhere that are only processed by those that care. Or using a more carefully designed subscription model, where a dispatcher sends messages to registered observers, and observers are themselves required to register interest.

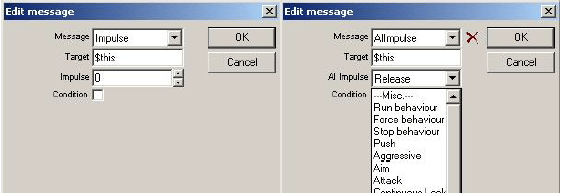

Fourth, and now we get into the work-intensive bespoke side of activation, we can send direct scripted impulses to objects we want to activate. This may be what we do in the other stages too, structurally, but the difference now is that we are starting to make connections by hand. When a player does X, I want this specific script to impulse this other specific object. Level designers will typically do this, and it’s usually what we talk about when we talk about “scripted” gameplay. Hard-coded logical gates, often using triggers activating when the player enters them.

Fifth, we can use timers to send impulses. Picture how a NASA shuttle would go through its many detailed course changes, rocket stage separations, and so on, with no direct input from the crew. All of it carefully timed based on the launch. Maybe one entry could be T+0.13: begin flap unfolding (no idea if there is such as a thing as a flap or whether it unfolds at any point; just an example). This way of triggering object interaction works much the same as digital animation, using a timeline or timed list. Your logic will step through the timeline and activate things as it reaches them. In its most primitive form, this is what you do when you add a Delay node to an Unreal Blueprint script.

Sixth and final, using systems for starting and stopping things, including other systems, is similar to what an industrial processor does. A “programmable logic controller,” or PLC, employs a style of programming that’s been designed specifically for non-programmers. It’s called Ladder Logic and defines its behavior from inputs and outputs. Of course, this differs from Blueprint and other instances of visual scripting since the ladder logic of a PLC is directly tied to physical inputs, but it’s conceptually quite similar. As it also turns out, this is an amazing metaphor for what a system is doing.

Look at this grossly simplified ladder logic:

—[Player Steps into Trigger]—[Door is Closed]—(Activate Door Opener)

If both of the first gates are passed (both “rungs” are climbed), then the trigger will happen and the door opener activates.

Fusion

Fusion is how things combine. There are two ways fusion is typically handled. One is that the sum of the parts defines behavior, non-destructively, and the other that a match of properties generates a new property or properties and removes the triggering properties.

If you look at something like the vehicle construction in Tears of the Kingdom, all objects have properties that will behave slightly differently in combination with other objects’ properties. This is the first type. Depending on your system, you may want to specify the fused behavior in some detail so that the player’s intent is considered. Sometimes the most chaotic freeform effects are unwanted.

Most cooking and crafting systems are of the second type, where combining two ingredients generates some kind of effect. This is safer, since the new object or property will simply replace the ones that triggered the fusion, so you don’t really need to make any exceptions after the fact.

Propagation

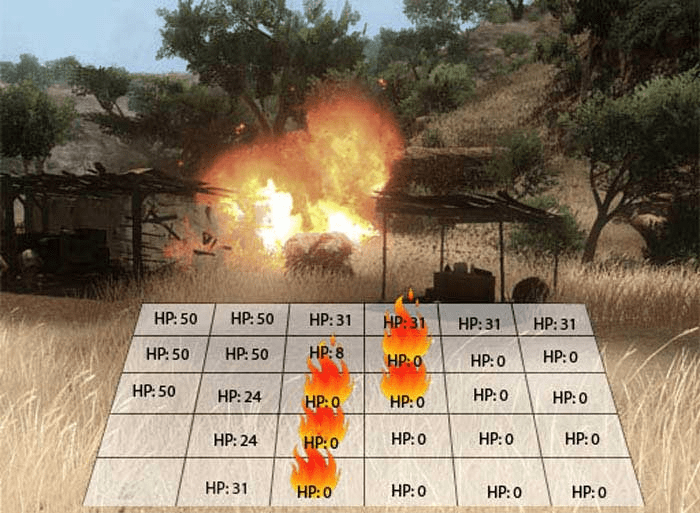

How properties spread between objects is known as propagation. You can do this in many different ways programmatically. An axis-aligned grid is used by FarCry 2 for propagating fires and is neatly affected by the direction of the wind.

This requires a whole separate abstract system, however. Sometimes it’s enough to just spawn additional objects with the same properties as the ones propagating.

Another way to communicate properties is through immersion or submersion. When you throw a wooden crate in the water, maybe it floats. This can be done as the water handling the buoyancy of any immersed object because of a set Float property. If the object is then fully submersed by the use of force, the counterforce created by this buoyancy may make it bounce back above the surface. Or maybe it fills with water and loses the Float property after full submersion.

Besides, what if it’s lava and not water?

Diffusion

Diffusion is the tendency of (mostly fluids) to dissolve and equalize. For properties, it’s an interesting concept in certain cases. Picture a space station, for example, where you need life support to maintain good air mixtures and pressure. If you could manipulate the gasses, you could do things like poisoning the air, removing the oxygen, or even drowning space station dwellers by mixing in water. The ratios of different gases would have a direct effect on the game space based on their diffusion.

Deconstruction

How things behave when they are destroyed can be a very interesting opportunity for systemic interaction. Deconstruction may simply remove properties, or it can cause other effects to trigger. It can also spawn new objects or introduce entirely new properties to nearby objects.

Think of breaking a container to spawn the objects inside it, breaking a door to gain access, or smashing an oil barrel to spill oil on the floor. Killing an enemy to steal its weapon and loot its pockets.

The last example is interesting, since it changes the properties of many objects. The weapon this enemy was holding is no longer held, but a weapon like any other in the game world. The enemy is often turned into a ragdoll.

That It?

This is not an exhaustive list of what systems can do. But thinking of objects, properties, and the manpulation of properties is a helpful way to get farther down the path to systemic design and development.

Consider how the same things can be applied to a social simulation, for example. A combat system. A survival game. The more you try to decouple your game development from explicit definitions and open them up to systemic manipulation of properties and traits, the more room will you also make for player experimentation.

If you think of something that is a glaring omission, don’t hesitate to tell me in a comment or at annander@gmail.com.

Thanks for your blog post :)! I really like your systemic approach to several things.

I’d like to know how you’d implement a basic system that allows the player to, let’s say, destroy a crate and loot its contents or destroy a wooden door or maybe push a metal crate, so it connects with something to solve a puzzle or something.

You talked about “interfaces” quite directly and I’ve made some “bad” experiences with that in previous prototypes, because, sure, interfaces are the first thing I thought about aswell.

IFlammable, IDestructible, IInteractable, IFreezeable, …

And it was nice at first, because I could easily implement IFlammable on my wooden crate AND on my wooden Door with their custom behaviour aswell. But now I need (?) to check if the interface is implemented (if object is IFlammable) if I want to set an object on fire with my fire projectile for example, which, in my case, resulted in a big if-tree mess. And I also need individual classes if an object is just slightly different, which inherently results in duplicate code. Let’s say I have my wooden Crate that implements IFlammable, but now I have another crate that is IFlammable AND IInteractable (a container or whatever), now I need to copy-pase the IFlammable implementation of my wooden crate over to the other crate and additionally implement IInteractable of course.

This got quite messy after a while and I’m not sure if it’s possible to find a better solution to that.

My current approach is more “data-driven” and I can set specific Handlers to my Objects that execute on certain triggers. This way I can add a FlammableHandler and an InteractableHandler to the object and if a projectile collides with this object, the object processes its handlers.

Therefore my “Bread” has an ConsumeHandler and if I press F while looking at the bread, the bread gets eaten. My ContainerCrate on the other hand has a ContainerOpenHandler which outputs the contents of the crate if I press F. Currently it’s only for interaction, because I’m still thinking about something like a “tag-system” where I can tag objects and handle these accordingly. So an actor could have a “friendly” tag, while my bread has an “edible” tag or whatever maybe.

I’m working with Godot and C# btw 😀

Hey Paragrimm!

The instinct to make things data driven to the extent possible is spot-on. Not sure you’ve looked at the companion piece to this article, located here: https://playtank.io/2023/08/12/an-object-rich-world/. It goes more into object-object relationships and various ways to structure them, including some pseudocode.

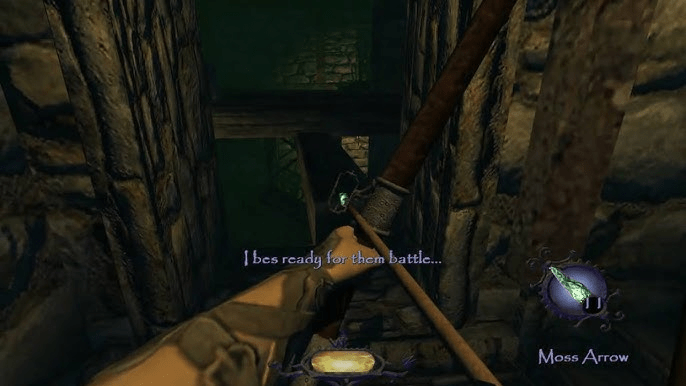

It’s quite common that the main point of interaction–particularly in action games–will be your physics engine. When objects collide, or when they within proximity to each other, they can then communicate their various states to each other. This is how old DarkEngine games used to do things.

In more modern games, you can use a functional intermediary (like “flame”), that gets created by one object and is then listened for by another object. This abstraction layer is akin to how a physics engine works.

There are other ways too, some of which I cover in the companion piece!

Hope that helps.