“[A]n object-rich world governed by high-quality, self-consistent simulation systems.”

Tom Leonard, Thief: The Dark Project postmortem

I don’t always use an epigraph, but when I do, I quote Tom Leonard describing the Looking Glass game design philosophy!

There’s not a single word in the quote that doesn’t warrant some further exploration. So let’s dissect it, nice and proper, with my own unsolicited elaborations.

Object-Rich

A world is object-rich if it leaves many things for a player to interact with. An immersive sim staple is being able to stack boxes on top of each other. Pick some fruit. Unlock doors. Open drawers and cupboards. Read people’s private journals, as well as the angry notes they’ve left for their neighbours. Open and close doors. Place tripmines. Drop heavy objects on guards to knock them out. Stack boxes, place tripmines that tip the boxes over, and then the boxes knock guards out. You get the idea. Object-rich = lots and lots of things to interact with and that interact with each other.

World

Whether we’re in a large open world, a carefully designed level location, or something in-between, this is a world we’re in. Not a gamified space but a living space that works as you’d expect it to. Not a place that has been set up for your gaming pleasure, but a living breathing environment. It does this most effectively by providing a narrative shortcut. You’re a thief, an assassin, a secret cyborg agent, or a survivor on a dinosaur island. It’s the piece of information that informs what you should expect. The fictional world as a framework for everything else, but also the game board that clarifies where the boundaries are. World = informative and contained, yet living and breathing.

High-Quality

Quality can be about graphical fidelity, sound quality, or it can be about contextual predictability and game feel. The point is to make the game feel smooth and nice to play. Atmospheric and interesting. Polished. This is the part that will take most time to achieve, and the part that scares everyone who will have to pay for it. Because systems won’t achieve this fast. In fact, many times our systems will be terrible for a very long time, until they’re not, and there’s no way of knowing how long this will take. But high-quality is crucial, or your incredible systems may end up feeling like bugs. High-quality = visually, aurally, atmospherically, and technically polished.

Self-Consistent

If one piece of wood burns, another also burns; even when it’s a door. If you can attach one thing to your horse shackles, then you should also be able to attach a Korok. Any rule that makes sense also needs to work. Things need to be more consistent and more predictable than they would be in real life, because this isn’t intended to be realistic but interesting to interact with. This is also why you so often find the example of fire and wood, because it’s such a simple and intuitive piece of logic. But Thief had its “rope arrows attach to wooden surfaces” rule; the same consistency applies. Self-Consistent = simple rules that apply predictably.

Simulation

Hidemaro Fujibayashi, when talking about the “chemistry engine” of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, talked about the importance of “natural phenomena or basic science facts.” Something moving gains momentum. Something heavy will push something lighter. A rope can be cut off. Fire can spread. Logs float on water. Actions cause equal and opposite reactions. All of the Newton stuff. Often with the kinds of intuitive rules that kids understand, but adults complain about. Like how a kg of feathers is obviously much lighter than a kg of lead. This is what you are simulating. Not necessarily realism, even if realism is what it starts from. Of course the log burns, it’s made of wood–who cares that you just pulled it out of the river. Simulation = basic science facts are reliably true.

System

A system can be thought of as a node with inputs, outputs, and feedback callbacks. This has been mentioned before. As you will soon see, where in your game you put the systems can vary widely between solutions. But the key difference between a feature and a system is that the system doesn’t care who else is listening. If you have a melee attack, for example, and you decide that it does X damage to enemies and that’s all it does, then it’s a melee attack feature. If you instead say that it outputs damage, and then other objects can accept damage as input and define their own behaviors as responses to said damage output, you’re working with a melee attack system. System = a piece of logic that turns data into other data, generates changes to state, and provides feedback.

Hello (Object-Rich) World

This article gets slightly more technical than the previous ones, but for a good reason. Systemic games are technical by definition. Your choice of how to make your object-rich world self-consistent will affect how your game feels to play on a fundamental level. But it will also affect how your game gets made and what requirements you will have to put on your development pipeline.

If you ask me, when people in the wild are baffled by how the Switch manages to push all the cool systems of The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, this is because they aren’t thinking technically enough.

A game is “just” data in the end. A realisation that may take some time to make. When programming for games, the sooner you connect that a floating point number is just a floating point number–no matter where it’s located–is the same moment that you’ll realise how powerful a game engine can really be.

You can store information in the UV channels of a mesh that gives your physics system material information. Encode how much damage a weapon does by using a single-pixel texture’s alpha channel. Save the pose of a character by storing the angle of its joints as just a single byte each, since the rig’s constraints are already doing most of the work for you.

Once your mind “clicks” with the notion that everything is just data, and you stop thinking too much like a user, it will allow you to do whatever you want.

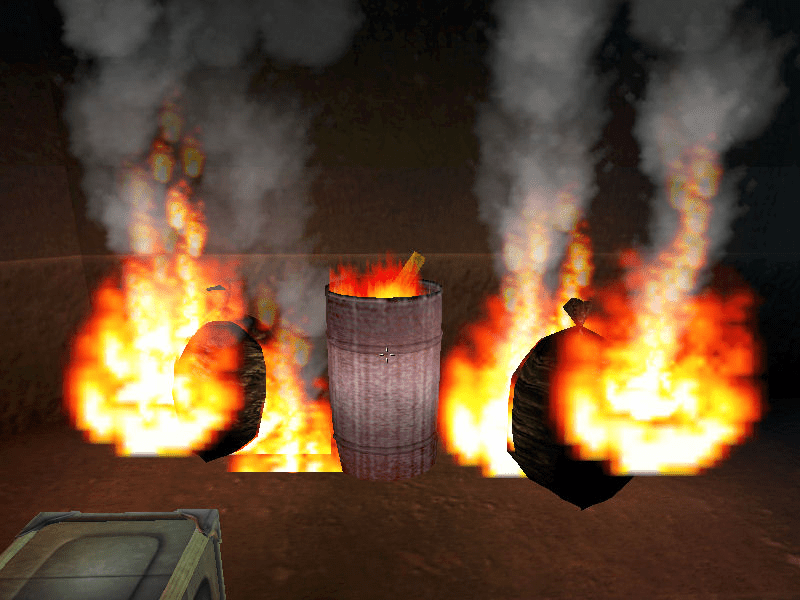

Objects

What an object actually is requires some thought. Here we’ll focus on objects that exist in world space. In Unreal Engine, this would be an Actor. In Unity, it would be a GameObject. What’s important is simply that these objects exist. Whether they’re characters, burning barrels, or something abstract, like the flame in the burning barrel, doesn’t really matter. They’re all objects in our object-rich world.

Direct Authoring

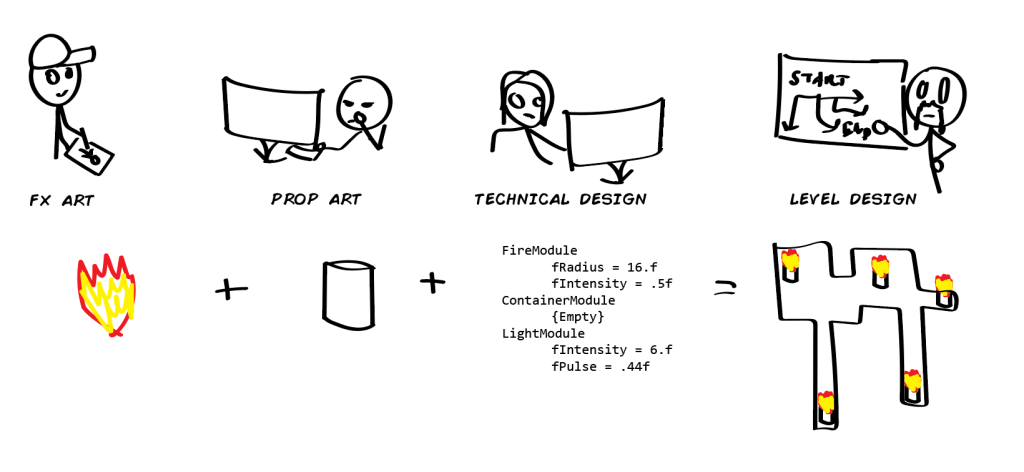

Probably the biggest difference between methods to handle objects is how they and their interactions are defined. Many systemic games are work-intensive, requiring level designers and technical designers who can carefully construct and map out the data used by the game.

It could be a prop artist that builds a metal barrel and an fx artist that creates the particle effects for fire and smoke. Then a technical designer needs to put the things together, usually in a custom tool, so that the barrel burns when it should and listens to the right types of state changes in the game world. In a systemic game, it’s never as simple as adding flames to a barrel to make a burning barrel–all of the systems must be hooked up properly for that “self-consistent simulation” to be possible.

Once the burning barrel object exists and has been set up correctly, a level designer places the finished result where it needs to be. Usually with some kind of restrictions, so that the whole level isn’t burning before you know it and that your hardware doesn’t choke on the fire and smoke.

With a direct authoring approach, you need to build every prop, every weapon, every piece of furniture, hook it up by hand, and place it manually in a level.

Modular Authoring

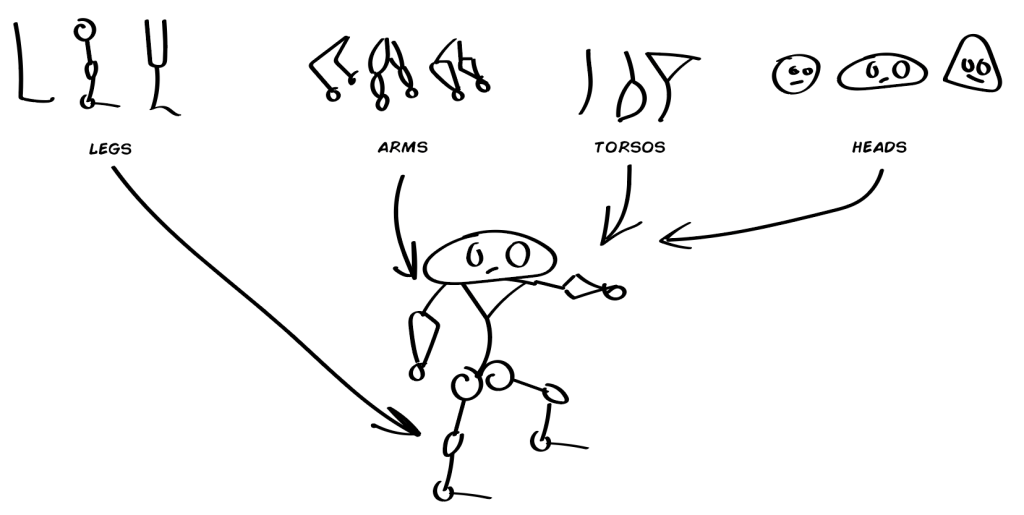

Building things in a modular fashion and making the authoring about putting modules together is of course just a variation of direct authoring, but one that does make a difference. One cool illustration of modular methods is the making of Bad Piggies. Of course, in that game, the modularity itself is also the gameplay. This isn’t always the case. But the strengths of building self-contained pieces of logic that can be combined in different ways are many.

Picture modular authoring as having buckets of premade behaviors that you combine into finished objects. Where this authoring is relevant can be limited, for example to only define projectiles or weapons using modules (like in the Building a Systemic Gun article), or it can be more generic.

Concepts like behavior trees and other graph-based tools all tie into the idea of modular authoring, where an AI’s different actions are described as tasks and a designer or other author is then responsible for defining when and for how long those tasks should be executed.

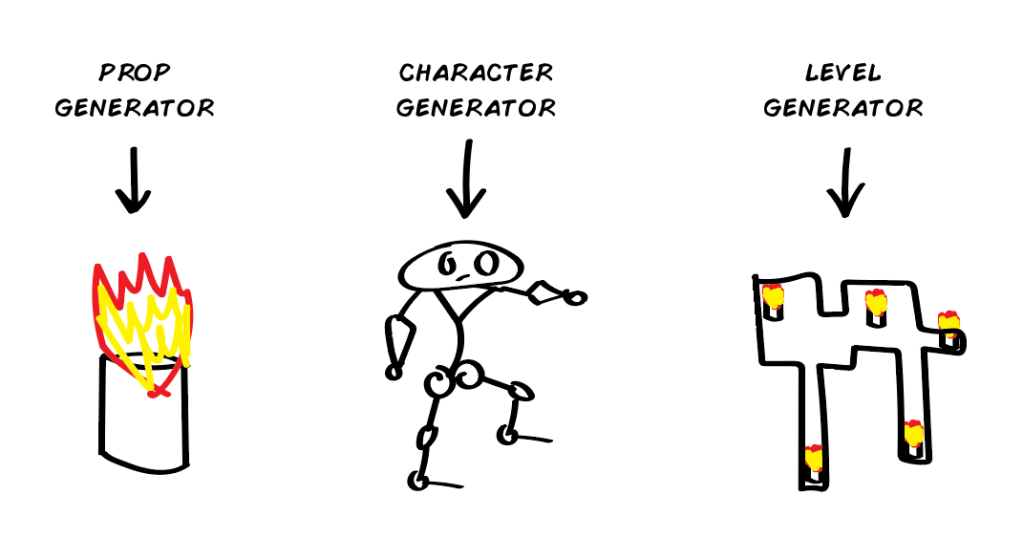

Procedural Generation

Lastly, you should consider procedural generation. This is usually a layer that replaces authoring at one stage or another, where you allow code to piece the modules together instead of authoring it manually.

Just know one thing: this doesn’t make it easier. On the contrary, procedural generation will require more effort and is often quite expensive to do, since you need programming resources and will likely have to iterate quite a lot before you get your money’s worth. It may be trivial to use a quilting-style or roaming generator to get quick results, but you will almost always run into exceptions that you don’t want, or complications based on your choice of algorithms. It’s also not uncommon that procedurally generated objects never quite reach the standards of their authored equivalents, and you end up using more time tweaking and tuning the generators than it would’ve taken to just make the stuff manually instead.

I personally love procedural generation, but you need to start from the result you want and design the system from that. If not, you will always risk building something because you enjoy building it, and not because it solves an actual problem.

Scripted Behavior

Some object behavior will be defined outside of the game simulation. This will be true for any tiles you have in your fancy Wave Function Collapse level generator, for example, or for lootable items meticulously placed into external drop tables. But also for enemy placement, predefined events, and everything constructed through a level editor.

In many systemic games, defining this behavior through level editors and other tools is a painstaking process that takes even more time than developing the systems in the first place. This makes good tools and therefore tools programming at least as important as the making of the systems themselves.

Having a foundational layer of scripted behavior defined by designers can be considered the default setup for most systemic games.

Loadtime Behavior

Loadtime behavior will typically decide which objects can or can’t spawn. Which dialogues can or can’t be considered. The simplest filter for this type of behavior will traditionally be which level you load, since this level will be filled with objects specified by a level or gameplay designer.

Some games pull from various pools of predefined assets to generate behavior. The most typical variant of this is procedural generation (PCG; i.e., using code to generate content), but it can just as easily be user-generated content (UGC) constructed from predefined pieces, mods of various kinds, or generation of enemy behavior.

The key thing with loadtime behavior is that it’s specified as a game session loads.

Runtime Behavior

This is what we’ll focus on the most. How objects affect each other while the simulation is running. This is where the key parts of our object-rich world happens.

Stim/Response or Act/React

Since this article begins with a quote from Tom Leonard it only makes sense to start with an interpretation of the Dark Engine approach: the Stim/Response or Act/React setup. You will find both terms used, and they seem to be based on who you ask. People who worked with the tools refer to the concept as Stim/Response or Stim/Receptron, for reasons you’ll see in a bit. But in the code it’s called Act/React. So I guess this might be a way to spot the programmers?

I have never worked with this engine myself, only glanced at it with curiosity, so do note that I probably get things wrong.

Imagine four types of “stims.” Triggers that may happen conditionally in the game world:

- Contact: sends itself to things it hits.

- Radius: broadcasts itself to things within a set radius.

- Flow: propagates to objects that enter the flow; flow of water or lava, for example.

- Script: further defined manually, by a content designer, in a specific level.

Pair this to scriptable responses. A response can be anything tied to object behavior. A simple example is how a banner in Thief will disappear if you cut it with your sword. That’s a SlashStim on the sword sending itself on Contact to the banner, and the banner’s SlashResponse is to destroy itself.

The beauty of this setup is that you can create complex behavior from combinations of much smaller pieces. It also allows you to ask “what if?” as you add strange receptrons to your objects, and the existence of the Script stim means that you can tailor-make behavior to specific circumstances. What happens if you apply a FireResponse to the banner? A WaterResponse? An AngryYellResponse? Or even, what happens if you apply that response to a specific banner on a specific level? The sky is the limit.

The only potential downside to the setup is that everything needs to be expressly coupled. Hand-crafted. It pushes responsibility for clever use of the systems onto the level designers and level scripters (simply “designers” in LG vernacular, it seems), making it a fairly content-intensive approach. But it also laid the groundwork for a style of immersive sim that has survived in the Dishonored games and Prey. If you haven’t played those, play them! If you have played them already, play them again!

class FireStim : public ContactStim

{

private:

float fFireAmount;

// Happens when contact happens:

void OnContact(Object ContactObject)

{

if(ContactObject.bHasFireResponse)

ContactObject.Response(fFireAmount);

};

}class FireResponse : public StimResponse

{

public:

void Response(float fFireAmount)

{

// Oh no! I absorbed fFireAmount of fire!

};

}Descriptive Trait-Matching (A+A)

The maybe simplest way to generate behavior is to make events the result of combining descriptive properties. Projectiles fired from your gun have DealDamage, for example, while their targets have TakeDamage (or both just have Damage). Or maybe combinations of cooking ingredients in your cooking system, with AddsSalt and WantsSalt.

The descriptive side of it means you can describe objects by listing their traits. An object that has DealDamage can be anything from a burning open flame to the bullet fired from a gun, but you know that it deals damage. This is isolated to the interactions between objects, however. These traits don’t necessarily describe the behavior of the object, unlike components in an ECS architecture (see Component Pattern, later), they only describe the interaction between objects.

There can either be identical traits represented by the same class, or you can have a setup providing negative and positive trait variants that need to be combined. That is to say, you can have a Damage trait that represents both sending and receiving damage, or you can have the DealDamage and TakeDamage traits described separately. If the two are combined, damage happens.

It’s really the same kind of thing as the Act/React approach, only simplified. You can now describe object interaction by listing positive and negative traits on the objects but there’s nothing in the trait that defines when this happens–that part would be up to another system.

This method is potentially less content-intensive than the Act/React method, since you don’t need to script anything explicitly once you have the logic, but is also dependent on some kind of triggering system to communicate traits and match them at runtime. It’s a good match for games where your interactive objects are fairly contained. Like the aforementioned guns and cooking ingredients, for example. It quickly becomes cumbersome if you want to describe lots and lots of object interaction types.

class DealDamage : public ActiveTrait

{

private:

float fDamageAmount;

public:

void Check(Array<Object> PotentialTargets)

{

for(int i = 0; i < PotentialTargets.Num(); i++

{

if(PotentialTargets[i].HasTrait<TakeDamage>())

{

PotentialTargets[i].Trigger<TakeDamage>(fDamageAmount);

}

}

}

}class TakeDamage : public ReactiveTrait

{

private:

float fHealth;

public:

void Trigger(float fDamageAmount)

{

fHealth -= fDamageAmount;

if(fHealth <= 0)

{

// R.I.P

}

}

}Subtraction (AB – B = A)

Imagine putting all the traits we want in a list and manipulating that list at runtime instead of just matching traits individually. Maybe it has three instances of Damage, one of Punchthrough, and one of Frag. The full list would then read Damage, Damage, Damage, Punchthrough, Frag.

Then we send this attack to the defender, as a message. But the defender has a list of its own, and any traits that also exist in the defender’s list are removed from the attack (subtracted, see?). Maybe the defender has pretty decent armor, with three Damage traits all its own. The defense list would then be Damage, Damage, Damage.

But that Punchthrough of the attack though, it will remove its CounterTrait–Damage–from the defender before the defender gets to do its defending.

A neat thing here is that subtraction can trigger feedback without any regard to how it gets triggered, making it possible to have different sounds, particle effects, or other responses for different hits for example.

This table illustrates how the subtraction could work:

| ATTACKER (Super-Duper Tank) | DEFENDER (Unsuspecting Armored Wall) | OUTCOME |

| Damage | ||

| Frag | ||

| Damage | ||

| Frag |

It could of course use arithmetic and not only match traits against each other. I.e., Damage 15 would be reduced to Damage 3 by a Damage 12 defender, but that would lose some elegance and clarity. My personal preference is to avoid player-facing numbers to the extent possible and push for interesting behavior instead. Though it’s obvious that games like Baldur’s Gate 3 doesn’t shy away from player-facing numbers!

For cases where you want bulk operations on traits, for example because your game has lots of upgrading going on, this is a pretty decent setup since it removes most of the authoring, except for potential modular pieces, and instead relies heavily on the combinatorial effects of different traits at runtime.

class Punchthrough : public Trait

{

public:

Trait CounterTrait = Damage;

}class Damage : public Trait

{

protected:

float fDamage;

public:

Trait CounterTrait = NULL;

void Trigger(Receiver Target)

{

Target.Health -= fDamage;

};

}class Attack : public Message

{

private:

Array<Trait> AttackTraits;

public:

void SendMessage(Receiver Target)

{

Target.Receive(AttackTraits);

};

}class Defense : public Receiver

{

private:

Array<Trait> DefenseTraits;

public:

void Receive(Array<Trait> AttackTraits)

{

auto TraitsResult = AttackTraits.Copy();

auto FinalDefense = DefenseTraits.Copy();

for(int i = 0; i = AttackTraits.Num(); i++)

{

auto AttackTrait = AttackTraits[i];

if(FinalDefense.Contains(AttackTrait.CounterTrait))

{

FinalDefense.Remove(AttackTrait);

}

if(FinalDefense.Contains(AttackTrait))

TraitsResult.Remove(AttackTraits[i]);

}

if(TraitsResult.Num() > 0)

{

for(int i = 0; i < TraitsResult.Num(); i++

{

TraitsResult[i].Trigger(this);

}

}

else

{

// Whole attack was blocked, JUST LIKE THAT!

}

};

}Abstraction (A -> B <- C)

So far, we’ve only interacted with objects directly. This has the risk of becoming quite inelegant over time, particularly if we need to be explicit with every object. The number of traits, stims, or responses, easily snowballs, and we may end up with duplicate solutions across multiple objects.

Another approach is to add an abstraction layer between different objects. Look at the things as senders, messages, and receivers. A torch sends a fire message; the fire broadcasts its firey fireness to anyone who cares; then receivers may pick up on the broadcast and read the message. The receiver doesn’t need to know about the torch, and the torch doesn’t need to know who could catch fire, or even that such a thing as fire exists.

This abstracted version is also the perfect place to inject rules, much like the chemistry engine of the modern Zeldas, or a physics engine that operates independently on rigidbodies.

A torch, as a simple example, would just own the fact that it causes a fire:

class Torch : public Source

{

public:

void Light()

{

Fire.Start();

};

void Douse()

{

Fire.End();

};

IntermediaryHandle Fire;

};The intermediary (or whatever you want to call it) represents the actual fire. Its job is to tell the world that it exists and to trigger fire-related things. It can also be part of a wider system or simulation (for example using a Component pattern) that handles propagation, lifetime, and game rules related to the intermediary in question.

This is really the same thing as a physics system and how it takes care of its colliders in a physics step. You can look at the intermediary layer as its own self-contained system, just like a physics system.

class Fire : public IntermediaryHandle

{

protected:

float fRadius;

FVisualFX SmokeAndFire;

public:

void Start()

{

SmokeAndFire = new FVisualFX();

};

void End()

{

delete SmokeAndFire;

};

void Update()

{

auto NearbyListeners = FindNearbyListeners<Flammable>();

for(int i = 0; i < NearbyListeners.Num(); i++)

{

NearbyListeners.Broadcast(this);

};

};

};Over there in the intermediary layer, the fire is doing its firey things. Anything you want to care about this fire, you simply make it a listener.

class Flammable : public IntermediaryListener

{

public:

void Broadcast(Fire)

{

// Receive the fire or communicate it to subobjects.

};

};Fuzzy Pattern-matching (A -Q> <R- B)

All games rely on the concept of state in one way or another. Current health. Current velocity. Current location in the 3D world. Any and all realtime data can be considered state. Maybe you have some kind of generic state representation in your game that can be used for relevant comparisons:

struct GameState

{

int iIdentifier;

union Value

{

bool bValue;

float fValue;

int32 iValue;

};

}But another way you can look at state is in a given moment. Then you can call it context instead. Context can be local, for example “I’m hurt,” because your health is below 50%. It can also be relative, for example “I’m behind my target,” or, “I’m above the objective;” context that describes the relationship between different objects.

bool Predicates::IsBehind(FTransform CurrentTarget)

{

auto Dot = Vector::Dot(Self.ForwardVector, CurrentTarget.ForwardVector);

auto NormalizedLocation = Self.InverseTransformPoint(CurrentTarget.Location);

if(Dot >= 0.75f && NormalizedLocation.X < (0 - CurrentTarget.Radius))

{

return true;

}

return false;

};Assuming you have a system for taking a snapshot of all current context, you could now get a good picture of the game state at any given moment. Even extremely complex state spaces can be described this way.

Maybe the list of context in a sample snapshot reads something like this:

- IsOutdoors:true

- IsMoving:false

- IsHurt:false

- IsBehind(Target):true

- IsOnLevel(MurkySwamp):true

- HasWeapon(Dagger):true

- IsFacing(Target):true

As you can see, each of these contexts will return either a true or a false: they are predicate functions. Imagine that this snapshot of context is collected at certain trigger points in your game. Which triggers a specific entity cares about may vary. Maybe they generate a snapshot when they spot a new enemy, or when they open a door, or when the sun rises, or some other gameplay-relevant thing occurs.

void TriggerEvents::OnSpot(Target SpottedTarget)

{

auto Context = WorldContext::CollectContext(SpottedTarget);

auto Query = Query(Context);

// If the context did return something that should happen

if(Query)

{

// Perform the action/response. Take the shot. Speak the dialogue.

Query.Action->Execute();

}

}For more on this excellent approach, in the context of dialogue, you should check out the book Procedural Storytelling in Game Design, where you can find Elan Ruskin’s description of the same thing he talks about in this GDC talk.

Component Pattern

One thing that all of the systems proposed here have in common is that you can describe objects using their modular components. That word–component–is the key factor in this last way of systemifying your game architecture.

An Entity Component System (or just ECS from now on) is based on completely data-driven approaches and attempts to decouple logic from data entirely. This can be done for performance reasons, as is the case in the ECS frameworks of Unreal Engine and Unity, but there are gameplay and systemic design reasons for you to explore ECS as well.

The heart of the concept is the relationship between its three core ideas.

An Entity is nothing but an identifier. It can be any unique identifier. It doesn’t contain any logic whatsoever, but in some variations the Entity is also used to store pointers to its components for easy reference. Unless you use an Archetype or Node (see below), this can be a helpful way to work with ECS more intuitively.

struct Entity

{

int iUniqueIdentifier;

};A Component only contains data. It can be a Position component, a Velocity component, a Mesh component, or something else. It has no idea of who owns it, who cares about it, or even what happens to its data.

struct PositionComponent : public IComponent

{

FVector Value;

};An Archetype (or Node) is a collection of components, decoupled from their Entity, that can be used as an accessible container for any System operating on exactly those components. Rather than fetching components using an Entity’s identifier, the System can store these Archetypes and make use of them without ever having to know anything about either the components or their owning entities. Just pointers to related components.

The Archetype is for convenience, and not strictly part of the pattern. But I’ve found that they make the code much easier to write, and that they make more sense to work with. You rarely only want a Position component–you want Position, Heading, Velocity, and maybe Radius–and that has now given you a Steering Archetype.

Archetypes can also collect all components of a certain kind, meaning you have a single Archetype for each concept a system operates on rather than having one Archetype per entity.

struct MovementArchetype : public IArchetype

{

PositionComponent Position;

VelocityComponent Velocity;

};A System is what actually contains the logic. A MovementSystem will operate on all Position components using their related Velocity components by adding the second to the first every frame. But the trick here is that this is all the MovementSystem does, and the only thing you need to do to give an Entity this movement behavior is to give it the required components (or archetypes), and the MovementSystem will update it along with everything else that moves.

One cool thing with this line of thinking is that you can bundle a lot of traditional entity-level logic into a system. A state machine can now switch between systems, for example, rather than having hundreds of instances of the same state. The lifetime of a system can also regulate specialized behavior. If you introduce an ExplosionSystem, for example, you could use a QuadTree or similar to make sure it only adds its velocity forces to Position components that are caught up inside its radius, and then gracefully destroys itself. (This pairs really well with object pooling, conceptually.)

class MovementSystem : public ISystem

{

protected:

Array<MovementArchetype> MovementArchetypes;

public:

void Update(float DeltaTime)

{

for(int i = 0; i < MovementArchetypes.Num(); i++

{

MovementArchetypes[i].Position +=

MovementArchetypes[i].Velocity * DeltaTime;

};

};

void AddArchetype(MovementArchetype NewArchetype)

{

MovementArchetypes.Add(NewArchetype);

};

void RemoveArchetype(MovementArchetype Archetype)

{

MovementArchetypes.Remove(Archetype);

};

};Finally, you need a Manager of one type or another. Some variations of the pattern will have one manager per subtype of Entity; others have a single manager that manages everything. You do you. Managers create instances, stores them, communicates between them, and updates systems who needs to know about them.

The greatest strength of the Component pattern is that you can maintain complex simulations without any truly complex code. It’s modular to an almost ridiculous extent.

Conclusions

This is really what it’s about. The system at the core of your systems. The oil in your machinery. The object-rich world emerges from this. But whether you choose to build your whole architecture around it, as with the Component pattern, or you empower your designers with the tools to do it manually, is up to you. There’s no silver bullet.

Personally, I like to hand power over to the systems. The less that has to be hand-authored the better. Not as a principle, though. Your game will most likely benefit from hand-authored content of one kind or another, no matter what kind of game you are making.

Oh, and as always, if you would like to know more, voice a strong opinion, or maybe book a systemic design lecture for your team, throw an e-mail at annander@gmail.com.

Hey, to follow up on my last comment:

Thanks for the pointer to this post, it really helped me to understand the concept better. I’ll try to implement it in our game inspired by the Abstraction approach you mentioned, since I want to avoid if/else blocks etc and a “Flame” Object just cares about flammable things etc.

I’ll also implement some kind of Trait or Tag System for my entities to be able to check whether an entity “has” or “is” “something” instead of using interfaces like IFlammable etc. Because i can define tags/traits in the editor and as data aswell in the end :).

What do you think of games like RimWorld? I really like the emergent gameplay that happens automatically. For example: if you start the game and survive the first raid, there will be corpses and almost everyone gets bad mood after seeing a corpse, so the graveyard concept emerges naturally, where you put corpses in places, nobody can see them, so they don’t get bad mood. All based on traits it seems.

Can you imagine how they implemented such systems and elaborate on that (there’s probably another blog post that covers that already :D)? It seems so much nicer and not content driven, but more systems driven, that I really want to look further into (I’ve read “The Content Treadmill” already btw). Because doing content is expensive and I keep asking myself if it’s even worth it from a player perspective. “Most people” (is there even a source for that? It’s just based on my hear-say perception though) even skip cutscenes or dialogue completely, so why add more of that in the first place?

Also, do you know some games that are worth studying that use such systems to some extent (especially more modern ones)? I’ve played (among others) Arx Fatalis, System Shock and Far Cry 2 already, so I know some of the older ones at least :D.

Your blog is really inspiring to me! I hope you’ll continue working on this :).

Definitely check out Prey, the Dishonored games, and the modern Zelda games—Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom.

In many cases, you want each system to be fairly self-contained. Your Damage System handles damage, it accepts certain inputs and provides certain outputs in response. For example. As you then start combining different systems is when the magic start happening.

With RimWorld and similar, a lot of the power is in the language and in association. A lot of the really cool stuff happens in your brain, through imagination. Dwarf Fortress is the same.