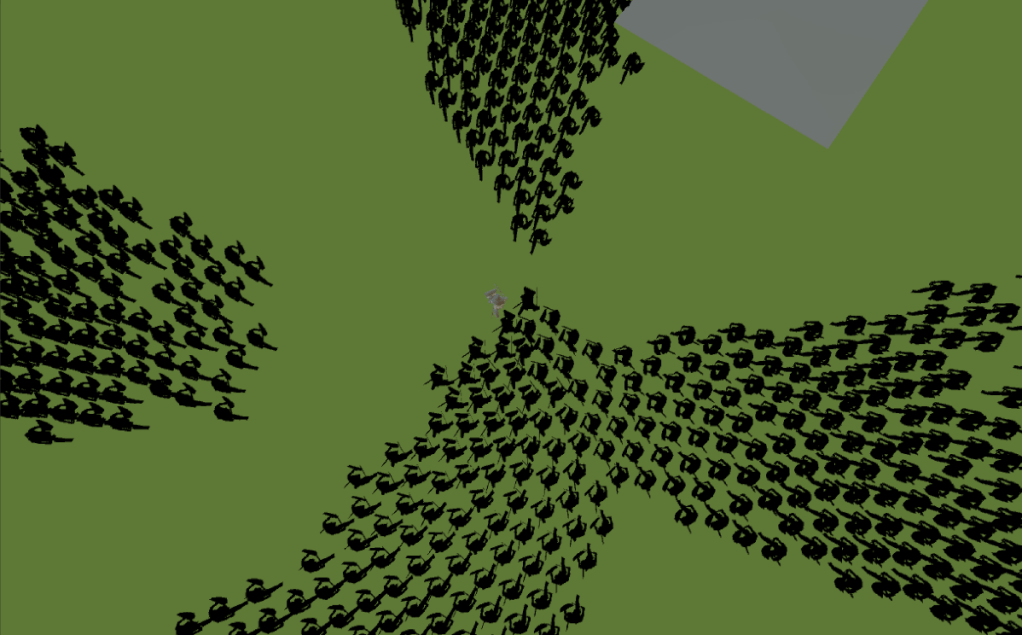

The biggest difference between designing a systemic game and designing its opposite (a content-driven game) is that you can’t know the exact outcome of every system and you must consider this state of mutability a strength. You must be willing to let go of your authorial control.

You can certainly define interesting interactions in advance, but a good systemic game will generate synergies that you didn’t expect. Some you will like, others you may not like. This means that designing a systemic game is about making things that follow a broad creative direction rather than a script or the whims of an auteur director. It’s a type of game where you want the player to have all the fun: not the developer or the computer (paraphrasing Sid Meier).

The following is a method I’m trying to use myself and wanted to share. It’s based on practical experience, some theorising, some experimentation, and a long line of past failures. It’s also being used right now on the first project I want to release as a solo developer, so let’s look at it as a work in progress.

The idea is to waste as little time as possible and to do away with as many assumptions as possible. Hopefully, this comes through.

Goal

Let’s first mention what the goal with our design is. There are two closely related things you’re after when designing a systemic game—synergies, and what they may lead to, emergence.

Synergies happen at the point of convergence between systems. This is the height of any systemic game—the point at which the game gains a life all its own. Once a game has enough synergies, usually by providing tools and consistent rules to players, it may achieve emergence. Unfortunately, there’s no magic sign or sudden revelation that will tell you that you have achieved this. Rather, you will need to test your game with a discovery mindset to be able to determine if there are enough synergies to reach critical mass.

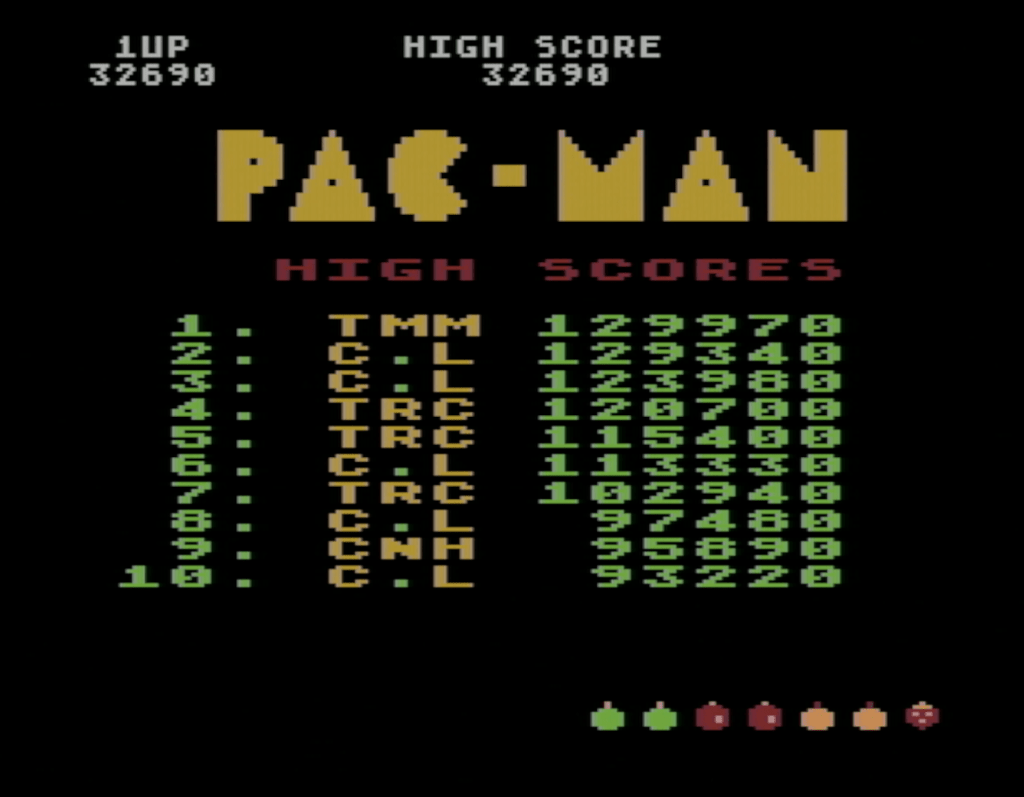

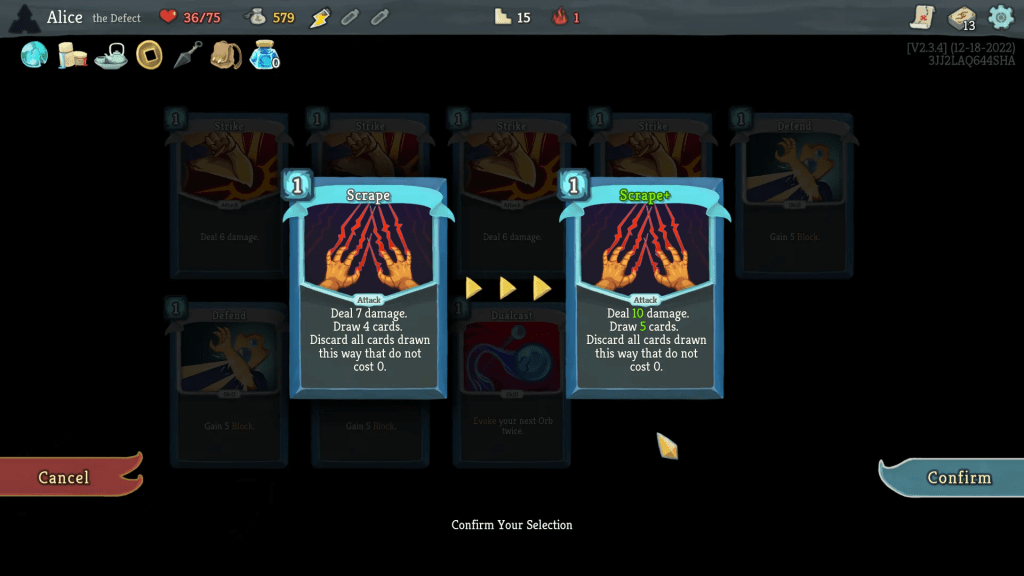

Emergence is a scientific concept that we have borrowed into game design. “An emergent behavior is something that is a nonobvious side effect of bringing together a new combination of capabilities,” says Science Direct. If you look at individual cards in Magic: The Gathering, their effects seem isolated. For example Enduring Renewal, which among other effects puts any creature that gets discarded back into your hand. It’s neat to be able to play them again, but nothing game-breaking.

But combining this effect with a creature that costs nothing to play (like Ornithopter) and another card that gives you resources when you discard one of your own creatures (Ashnod’s Altar), you can suddenly generate infinite amounts of mana by continuously playing, discarding, and getting the zero-cost creature back to play to discard again. Ad infinitum. This is an example of emergence that players could discover based on the synergies of separate rules, but that were probably not intended by the developers. (Clearly demonstrated by the card Enduring Renewal quickly becoming Restricted in tournaments, limiting you to a single copy of the card in a deck.)

Words

When the following words are used in this article, this is what I’m referring to. It’s critical to keep track them, because all of them are things you can get stuck on that don’t actually makes your game any better without careful planning.

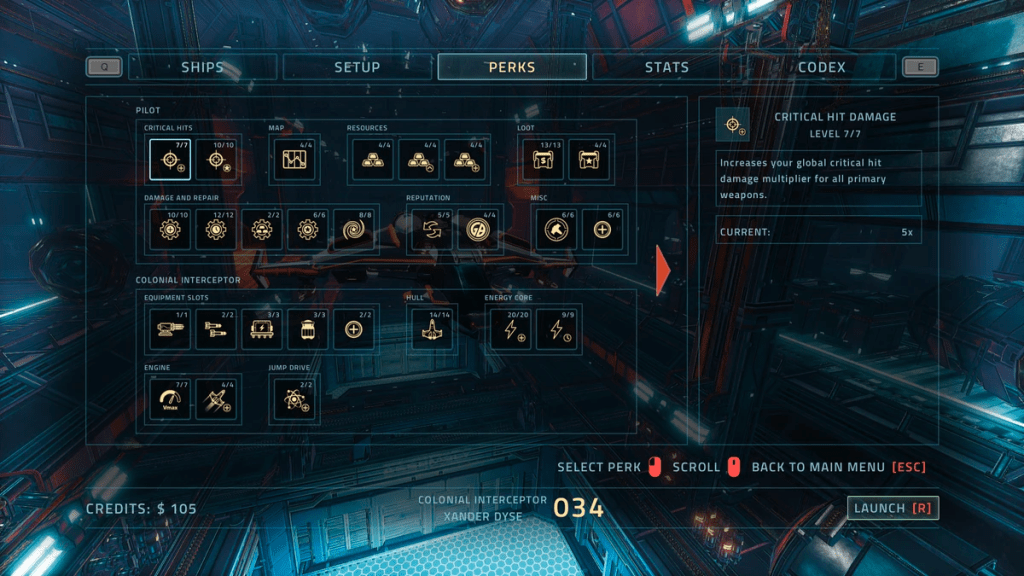

A feature is something that always behaves as expected, because it’s isolated from other features except where expressly implemented. A feature has very clear boundaries and clearly defined specific interactions that a player can learn to make use of. The biggest issue with a feature is that it’s systemically dull because it doesn’t provide any interesting interactions with other elements of the game except where the code expressly allows for it. This means that feature-rich games must generally keep introducing new features and/or provide other forms of content to keep the player interested. It’s the bread and butter of content-driven games, but completely antithetical to systemic design. Unfortunately, features are what we most often design.

A technology is primarily developer-facing. Confusingly, you can still refer to technology as “systems,” but a technology rarely solves any product-level problems. It’s the character system that renders and animates characters, or the procedural generator that spits out playable levels. It may be required to make your game happen, but technology requires tools and extra work before it can produce any tangible player-facing results. It’s therefore risky to work primarily with technology if your goal is to make a game.

A tool is something that packages a system or technology. But the tool itself is never going to make anything better. There needs to be a plan for who will work in the tool and what the output of the tool is supposed to be. If not, you will be accumulating what I call “work debt,” where you are pushing the actual work forward while you make the tool.

Furthermore, a system on its own can behave much like a feature does, except it’s usually harder to make and therefore makes little sense on paper. The real magic doesn’t happen until you combine systems in interesting ways, meaning that a systemic design will only be worth it when you have multiple systems interacting. Building just one system on its own becomes just another name for technology or feature.

TL;DR: Features can be listed and planned for but provide zero overlap. Technology won’t give you anything without additional data. Tools are usually necessary but won’t do anything if no one works in them. Systems can only achieve anything when combined with other systems. You will have to address the shortcomings of all four if you want to develop systemic games.

Components

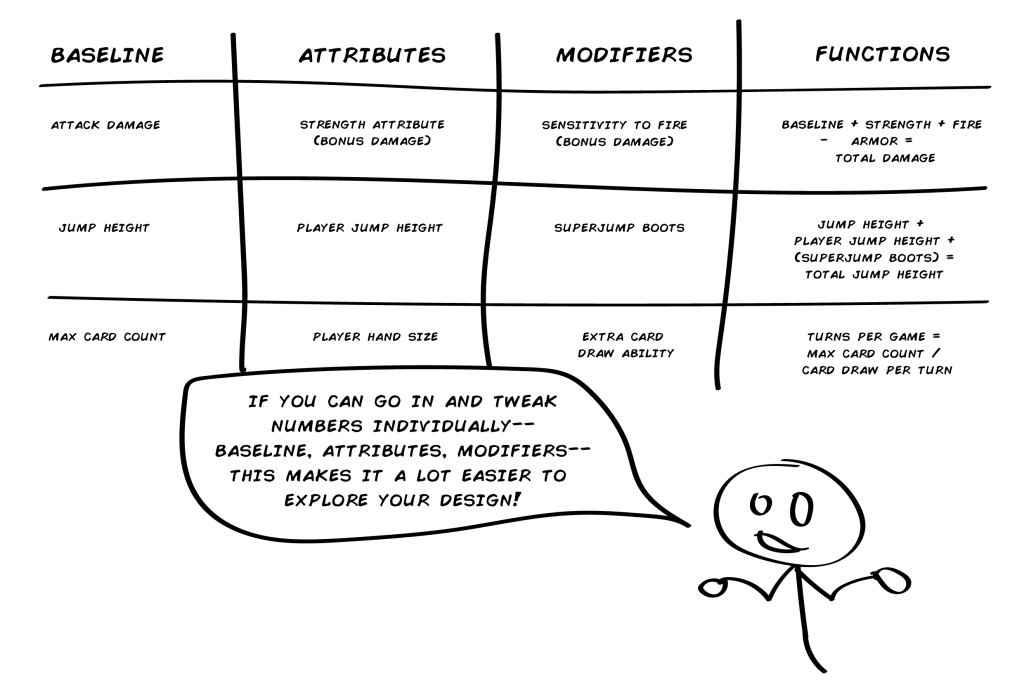

We must also know what our design needs to deliver. Since it’s more or less impossible to design synergies directly, we’ll be designing for synergies instead. This is different from writing specifications or feature lists. To design for synergies we need to set everything up in such a way that it can interact and that all those interactions point in interesting directions.

Verbs

It’s almost cliché to talk about verbs in game design, but for good reasons. Verbs represent the fiction we’re presenting to our players. They’re not pressing or clicking buttons; they’re dancing, jumping, fighting, kicking, biting, eating, building, and so on.

An important part of designing verbs in modern game design is that it doesn’t imply control schemes. Instead, you should describe the actions represented in the game and you can then map that to whatever input your target platforms support or your users customize. If that’s touch input, controllers, mouse and keyboard, something like the Microsoft Adaptive Controller, or something else, this can remain abstract while you design the game.

Setting and Locations

You don’t learn all that much about Tatooine when you watch Episode IV. It’s a desert planet, there are moisture farmers and there’s a limited Imperial presence because it’s in the Outer Rim. This is part of the setting of Star Wars. The cantina where Han shoots first is a location.

Think of the setting as the frame and the canvas of the painting as the location. In a game like Tetris, the setting is a vague Russian theme implied by the artwork while the location is the boundaries of the area where you can place playing pieces. In something like Gothic, the setting is a fantasy world with orcs and swords, while the locations are specific cities, roads, clearings, etc.

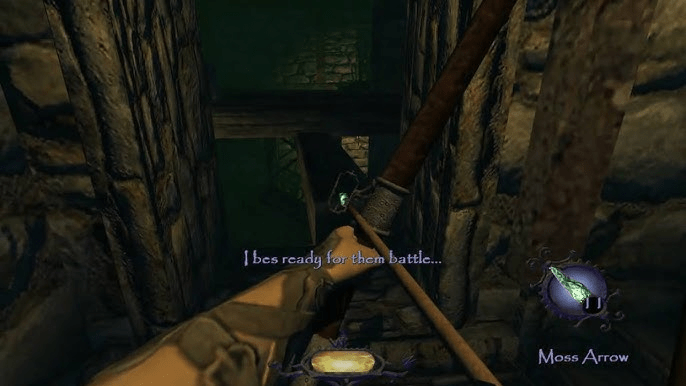

Oh, and for Thief: The Dark Project, since I always fall back on it anyway, the setting is The City, and the locations you play are the individual levels.

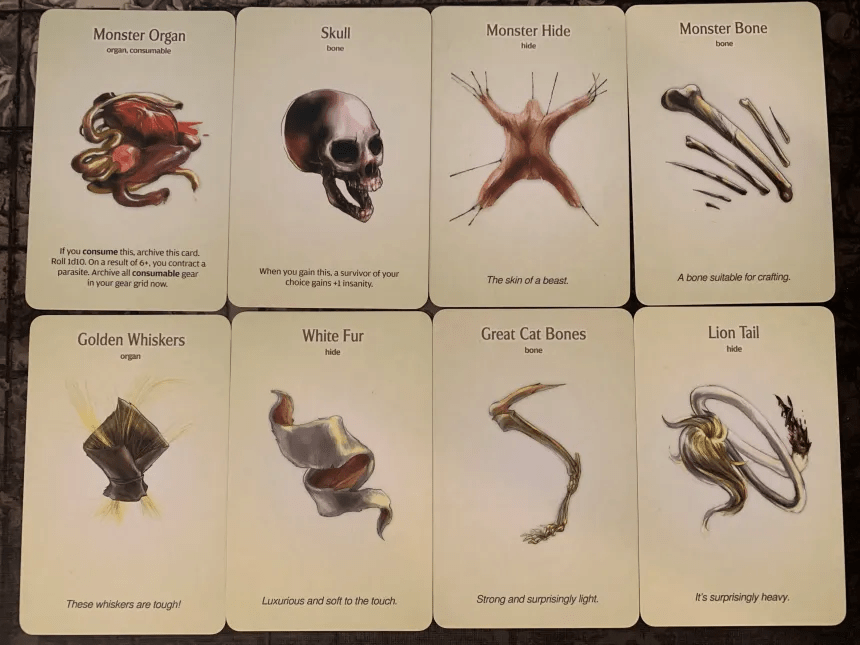

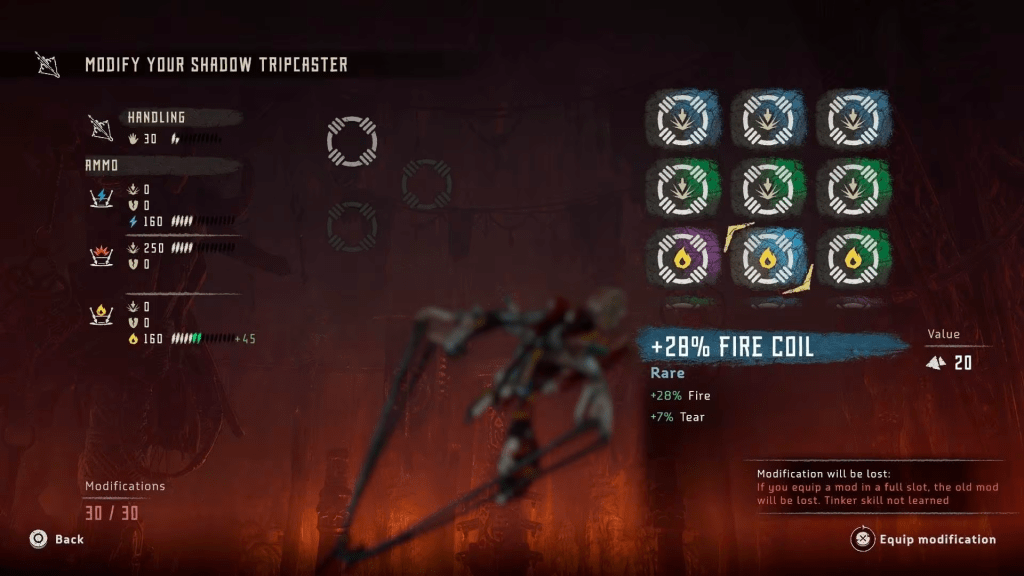

Objects

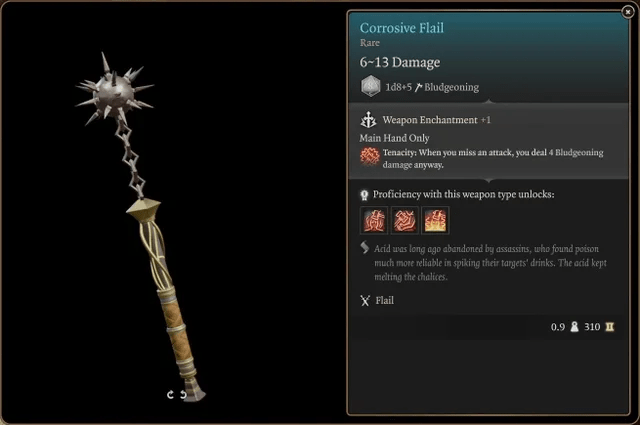

Systemic design is object-rich. Object is the broad category of every interactive thing that exists in the game’s simulation. The high level object in your game engine can be a GameObject, an Actor, an Item, a Token, and so on. I call them simply “objects” here because it’s a neutral term, but many engines reserve this specific word for engine-side shenanigans so it can be helpful to come up with another term for your specific game.

Characters

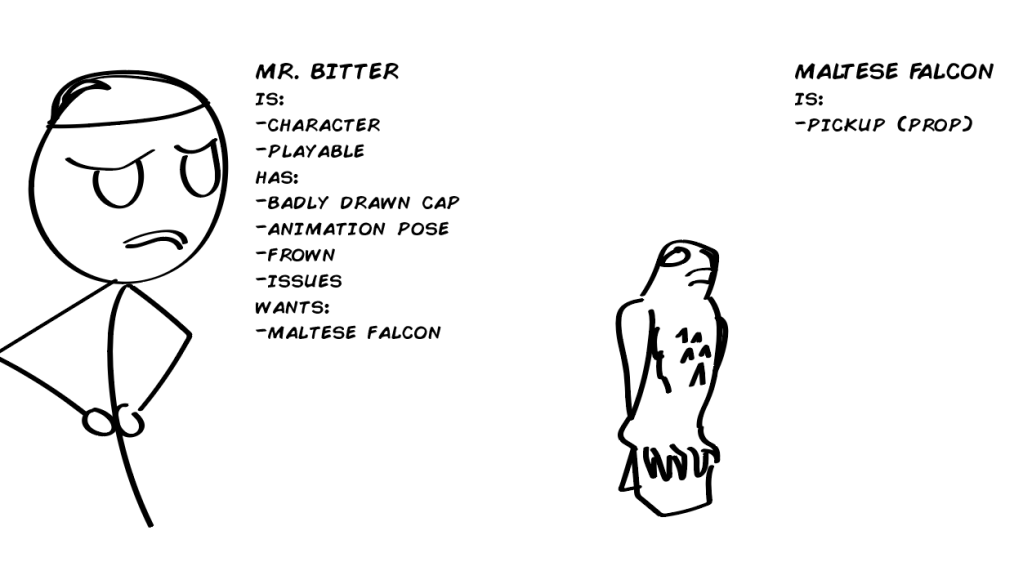

Characters don’t have to be standing on two legs or talking. They can be animals, space ships, suicidal scifi-doors, a metal crate with a heart on it, or something else. All of them are characters.

Captain Reynolds in the Firefly show is a character, but so is the space ship Serenity. An individual guard can be a character, but in most functional ways (such as who likes who) the City Watch faction is also a character. It helps you to think of it this way because it will help you define rules later on.

- Objects that can interact with and react to other objects in meaningful ways.

Props

Props have no agency. They are the levers, items, guns, refrigerators, and inanimate mining blocks that characters interact with. How your design relates characters to props can be interesting, since it runs a wide range from simple MacGuffins that are never actually interacted with but merely sought after, to utility items. Props can be possessed by characters, activated by characters, destroyed, etc. More on this type of stuff here.

- Objects that can only act on other objects by being triggered by a character.

Devices

A plot device is also an object. A piece of state that may inform a game’s narrative layer, such as “the king is dead,” or stated facts such as “the roof is on fire.” The difference between a device and other objects is that a device doesn’t have the same type of representation in the game world. It’s something that informs the simulation but isn’t manipulated by characters directly.

- Objects that have no representative form but still affect the game’s state-space.

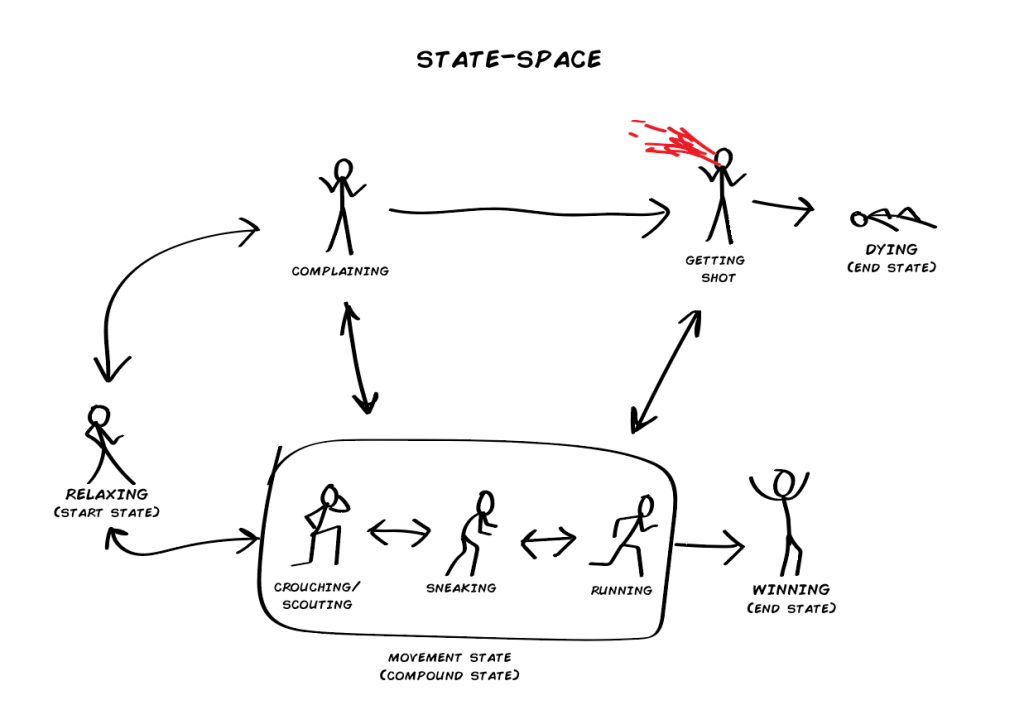

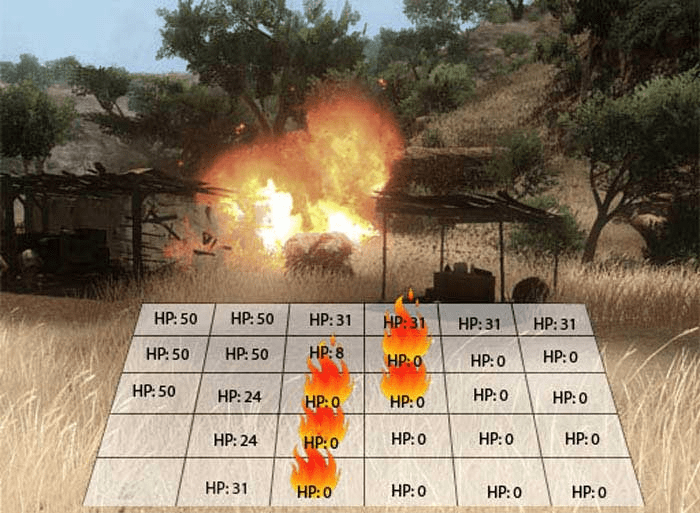

States

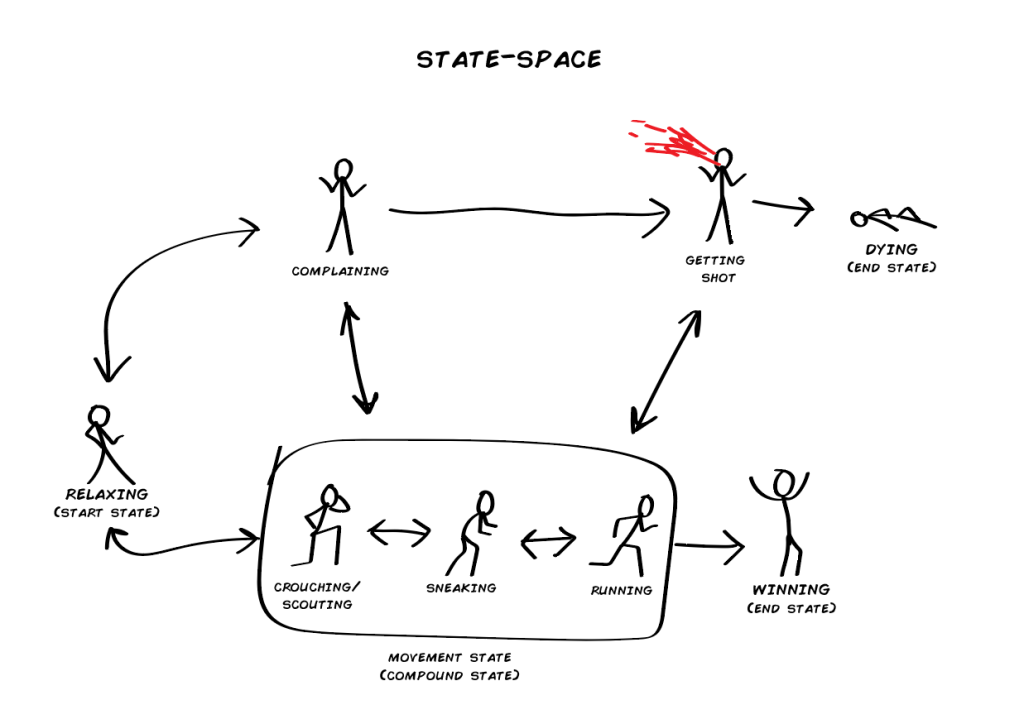

The state-space is something I’ve covered in various forms multiple times. This is because it’s what makes a game happen. I won’t be reiterating things stated elsewhere, but will repeat an image from the linked post:

Rules

“Every complex system starts as a simple system that works.”

Amy Jo Kim

When you have all the components, you need to decide how they interact and you do this by writing rules. Unlike a board game, we won’t require our players to read the rules. Instead, we must make the rules so clear that they make intuitive sense.

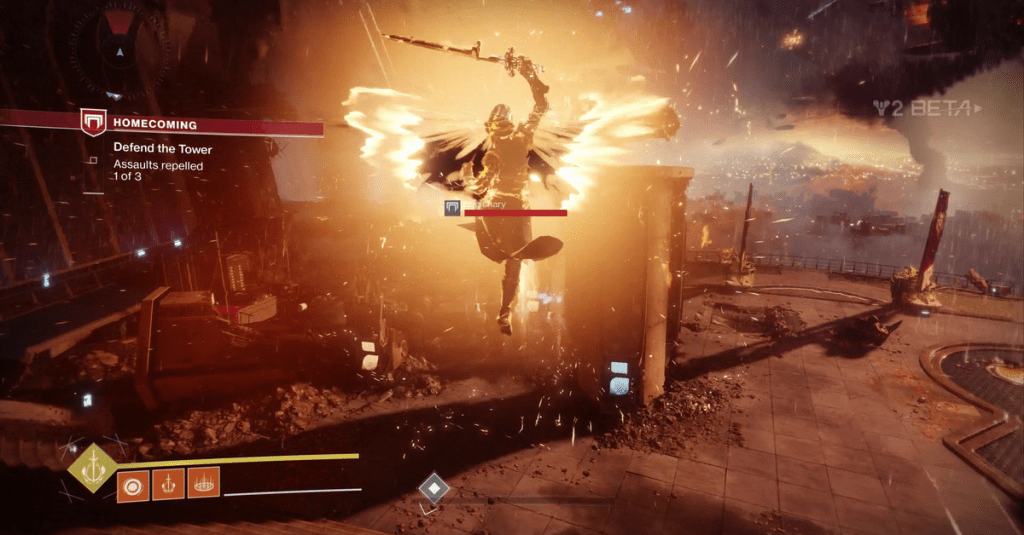

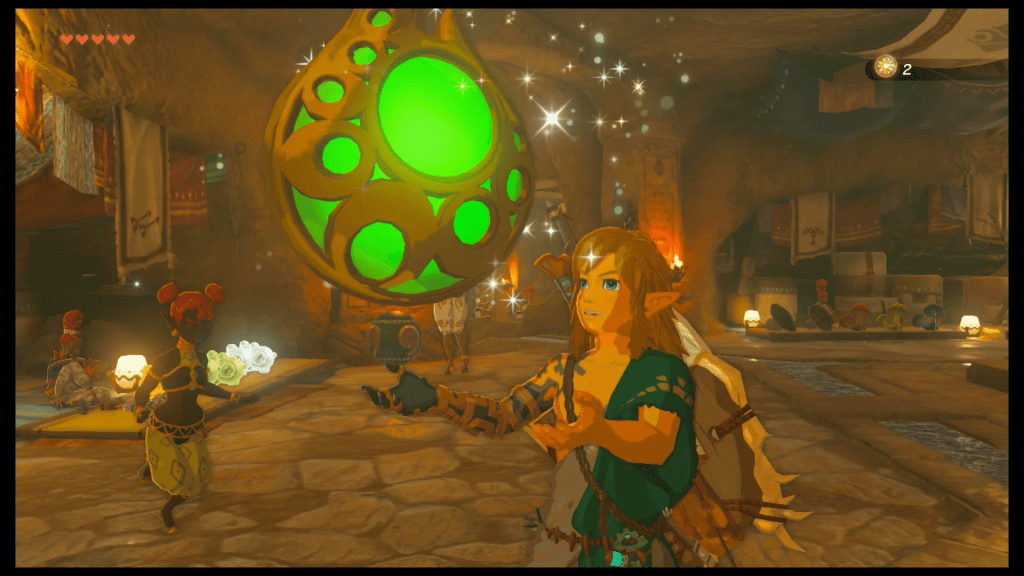

Thief: The Dark Project has its rule that rope arrows attach to wooden surfaces, for example, while The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (BotW) takes its cues from “natural phenomena or basic science facts,” according to its developers; wood burns, metal leads electricity, wet rock gets slippery, etc.

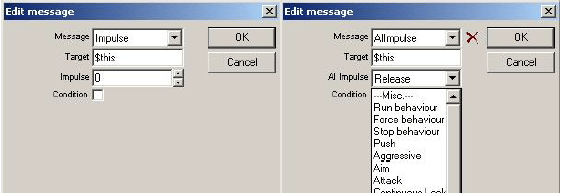

Rules can be divided at a high level into permissions, restrictions, and conditions.

Permissions

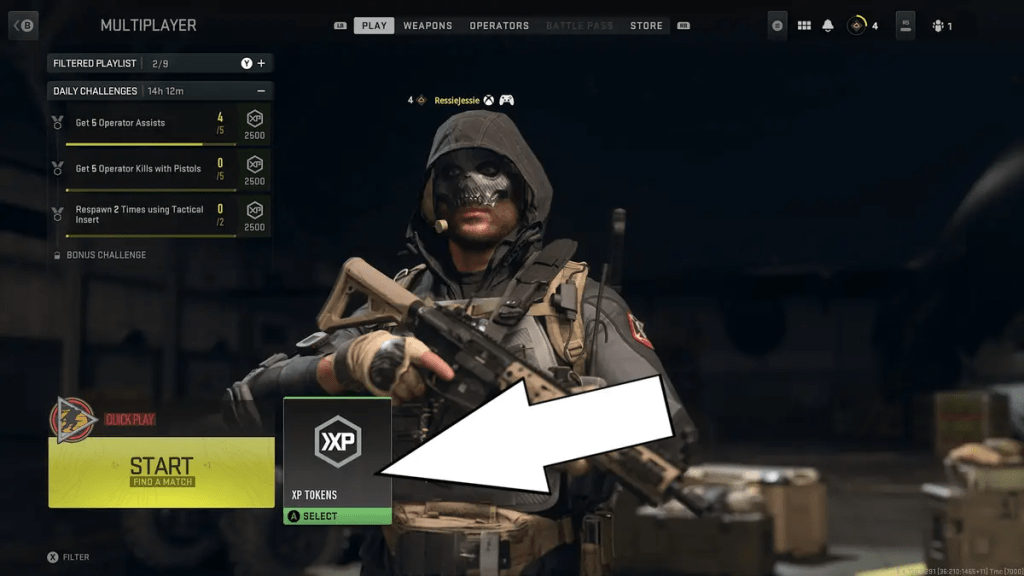

A permission allows something. Permission to move into new rooms. Permission to climb ledges. Permission to collect gold. Permission to jump, open doors, kick people in the chest, build kitchens, train horses, respawn after getting killed, and/or eat hot dogs.

Each permission also has a defined outcome. It’s like an “if”-statement in programming. If you activate the door, the door will open. This is an object-level interaction; a character (your player avatar) activating a prop (the door).

- Permissions define character-prop or character-character interactions.

- Permissions define outcomes to said interactions.

Restrictions

A restriction can be an exception to a permission, such as being unable to open locked doors without unlocking them first, or it can be a more general restriction such as not being able to open doors that are locked at all or having to stay inside the boxing ring or you get disqualified.

This last part is important, because a restriction also needs consequences. The consequence can be that the game simply disallows the restricted thing, but it gets more interesting if the consequence has a playable effect. You can climb wet rock faces in BotW all you want, but it will be a frustrating and Stamina-draining experience compared to waiting until the rain passes.

- Restrictions define exceptions to permissions.

- Restrictions define consequences to attempts going against them.

Conditions

Lastly, conditions are the rules that frame everything else. Things like how a game starts or ends, or how you win or lose. This isn’t always tied into the permissions or restrictions of your game, but it can be. For example, it could be that after you’ve opened all the doors the game tells you its narrative secret and is then over. A condition can also be the rain in BotW, that modifies the state-space on a global level.

- Conditions define framing for permissions and/or restrictions.

- Conditions define high level rules for the game state.

Designing Systems

“It’s not about how clever and creative you are as a designer—it’s about how clever and creative players can be in interacting with the game world, the problems, and the situations you create.”

Warren Spector

Game design risks becoming a kind of introspective navel-gazing at its worst. To prevent this, one way is to divide it into six separate stages with clear practical deliverables at each stage. You can meander a bit between stages, but you can never go back to the first three stages once you have passed the Commitment stage. Then you must stop entirely with the “fluffy” parts of design.

One reason is that you actually need all these stages. If a coworker asks you to deliver a finished design before you have been able to pass through Exploration properly, you are likely to commit to something half-baked that may have to change down the line. This costs time and money, and easily causes frustration.

Stage 1: Ideation

In ideation, we ideate. For a systemic game, this is about identifying the components and rules we think that our game needs. Contrary to most developers’ gut instinct, this isn’t the time to write code or build prototypes—it’s a time to figure out what systems you need. Writing the code is about turning a design into something concrete, but if you do this too early you will miss important pieces of the puzzle and you are likely to waste a lot of time on things you don’t actually need. This is where a heavy emphasis on technology often comes from.

Core Idea

Whatever concept you choose should be used to inform the rest of your game. Part of Thief: The Dark Project‘s genius is that you can adopt the game’s mental model straight from the title. You’re a thief—you will pick pockets, steal valuables, burglarise manors, etc. All of it makes sense.

The core idea can start from many different types of concepts but will be informing everything you do and therefore needs to answer the 5W+H questions around your concept. It needs to tell a story, not as a narrative but to provide a mental model for the player.

Some examples of what you can start from:

- A conflict: winning the race, the tournament, championship, etc. Not always as clear-cut as this. Many survival games fall into this, since you’re competing against nature from the perspective of classical literary conflicts.

- A role: the thief, the bodyguard, the soldier, the news reporter, the paladin, the cat lady; whichever role you set, it’s one of the most powerful core ideas you can have and will help you figure out all the other things much more easily. Think of what mindset you want the player to have; what role-play you want them to get into.

- A goal: finding your missing parent, delivering your dead wife’s ashes, avenging your murdered family; you can let a strong goal define much of what your game is about. A game about vengeance is likely to be violent, for example.

- A story: starting from a narrative core idea is actually quite dangerous for systemic games, because there’s a great risk that you start writing scripts and having assumptions about what the players will be doing, feeling, etc. But having a few central beats, factions, etc., that you start from can definitely help, and is also where you’re bound to begin if you are using an existing IP. Approach it how you can write an adventure for tabletop role-playing games: prepare the premise, but don’t prepare the plot.

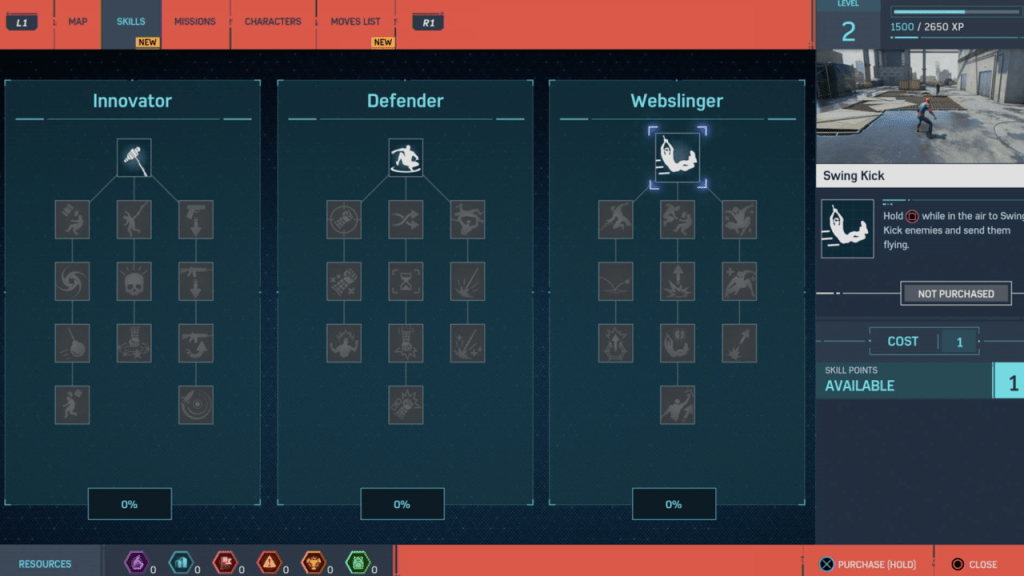

Activities and Resources

Given the core idea, you need to figure out what the main activities are. The things you do all the time as the foundation for the game. Avoid making this a list of features, however. Write verbs at a fairly high level at first. “Fight,” for example; not “Quick Attack, Heavy Attack, Low Attack,” etc.

You’re working from a fiction to start with and should avoid contaminating your vision with game parlance for as long as you can. Most definitely avoid genre labels at this stage, because the conversation that follows convention will always be one about definitions, and this conversation won’t help your game design.

Connected to your activities, you want to figure out the key resources of your game and how they are handled. A resource can be health, time, stamina, gold, or something else. Every game has some kind of resource.

With activities and resources summed up, you move on to the rules. Permissions, restrictions, and conditions. What happens if you run out of the resource, or gain too much of it. How the resource is regained if it’s lost, if it can be regained at all. How the game ends, how it begins, how the resources designed progress through that flow. Once you know what can go wrong, you figure out what happens when things don’t go wrong and how that can be used to incentivise the player.

Systems

To be able to start exploring you need to sum up all the systems that must be tested. Keep this simple at first. If your game is a driving game, it’s likely to have a system for car customisation (a Car System), one for driving (a Driving System) and another for the track (a Track System). That can be good enough to start with, even if you know that there’ll have to be a Competition System to keep track of the score and lap count, as well as an Opponent System that drives AI cars on the track.

Also note that systems aren’t exclusively about gameplay. Depending on the size of your team, you will also want to explore technical art systems, animation systems, sound systems, and systems related to all other areas of your game

- A list of high-level systems that you will be trying out in Exploration.

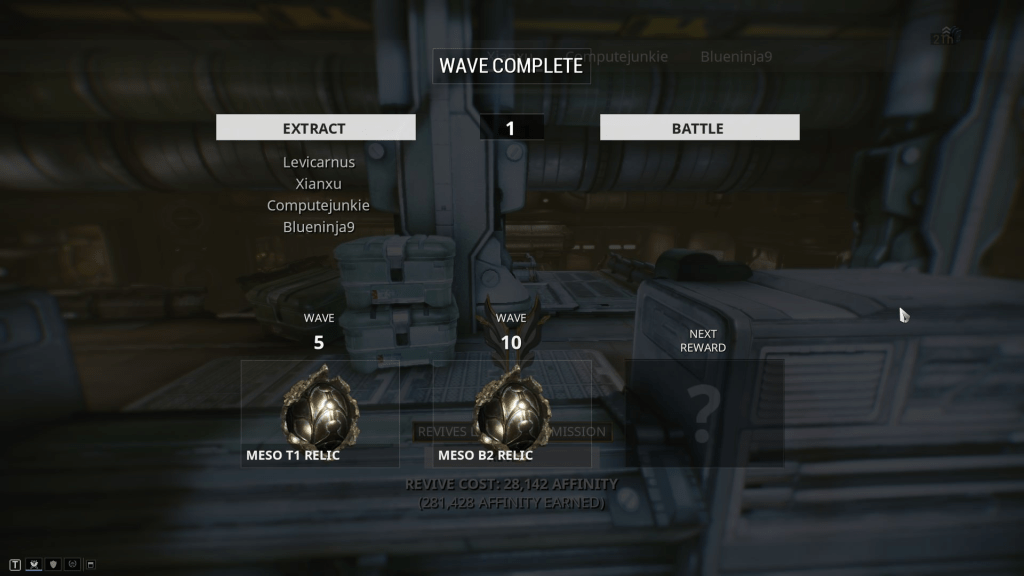

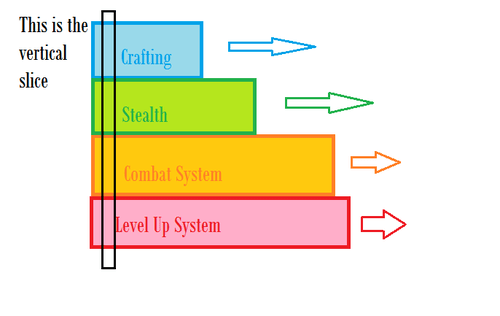

Stage 2: Exploration

Once we know what we want to be immersed in, we can move forward into exploration. The trickiest part of all comes up here: it’s impossible to test synergies without multiple systems to synergise. This means that exploration will take longer for a systemic design than for most other types of games. It also means that you can’t test things in isolation, because it won’t tell you anything about the validity of your design.

Many game projects plan the bulk of their time for production. Making levels, assets, content. For a systemic game, since exploration and preproduction are more time-intensive, you need to put a much bigger emphasis on exactly those areas.

My ideal is to put 50% of your time into prototyping/preproduction and wait until the second 50% to do any production. In reality, this is rarely feasible because of hard deadlines or stakeholder demands. (Incidentally, one of the many reasons I think gaming has been afraid of systemic development for a couple of decades.) But at the very least, make sure to put a lot of time into testing your assumptions. Because some of them will be wrong, and you don’t want to find this out after having already spent all your time and money.

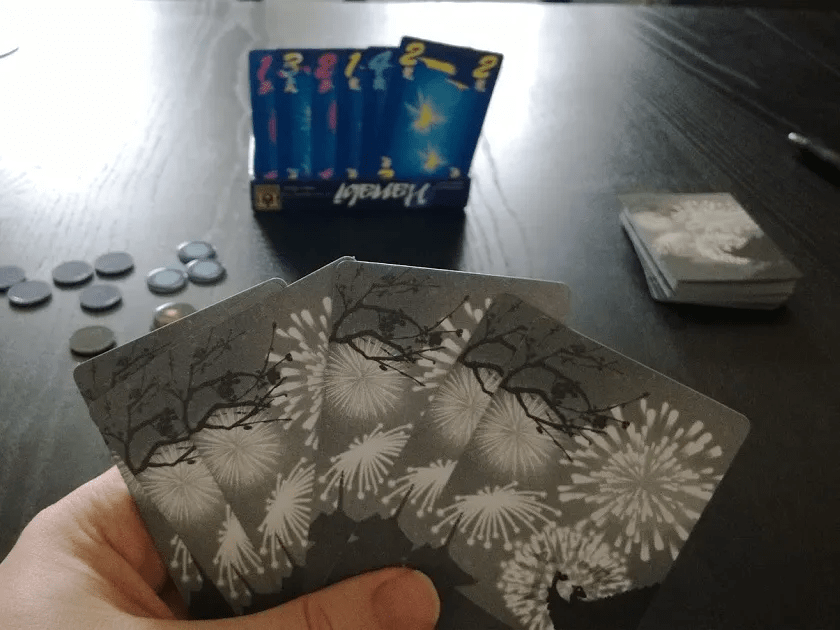

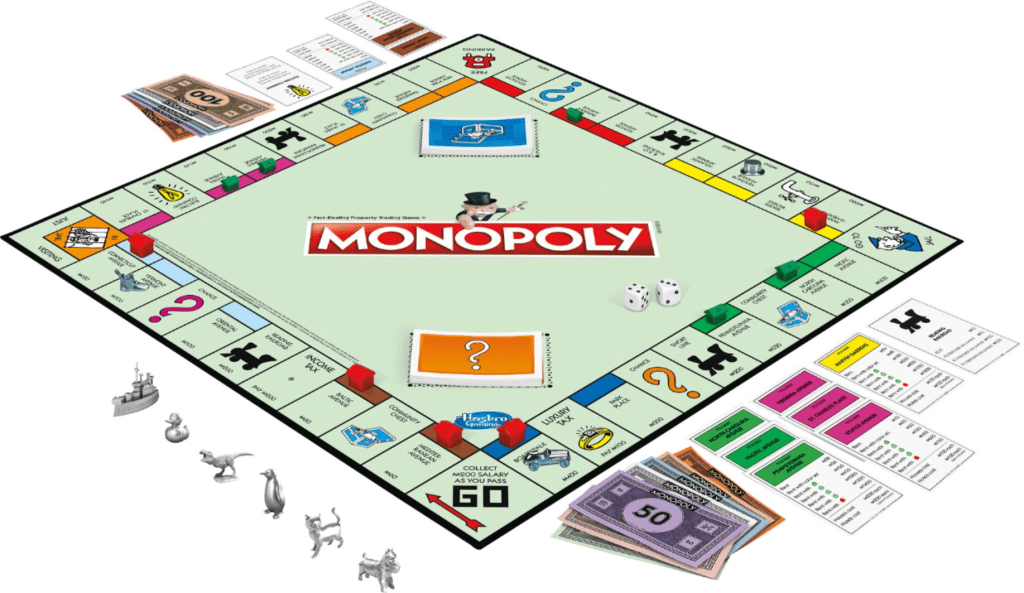

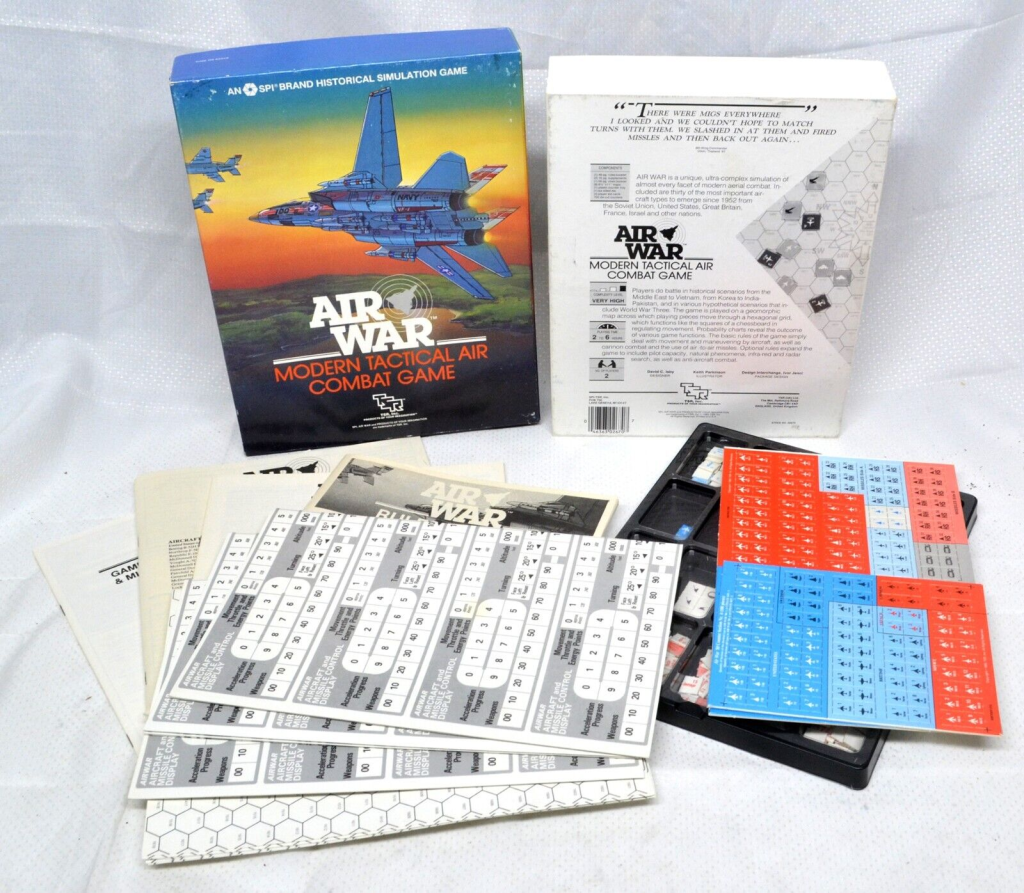

Analogue Prototyping

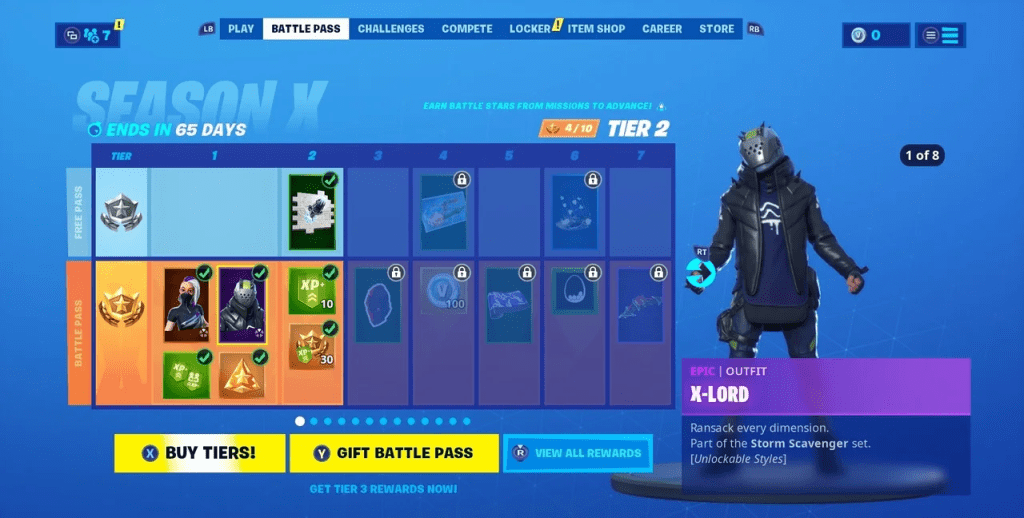

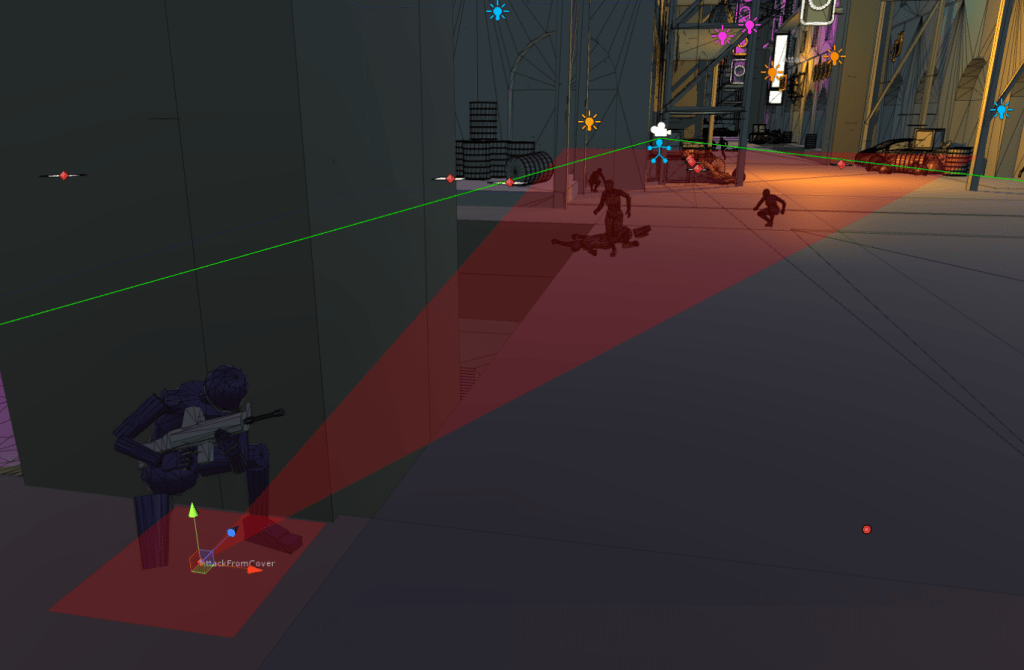

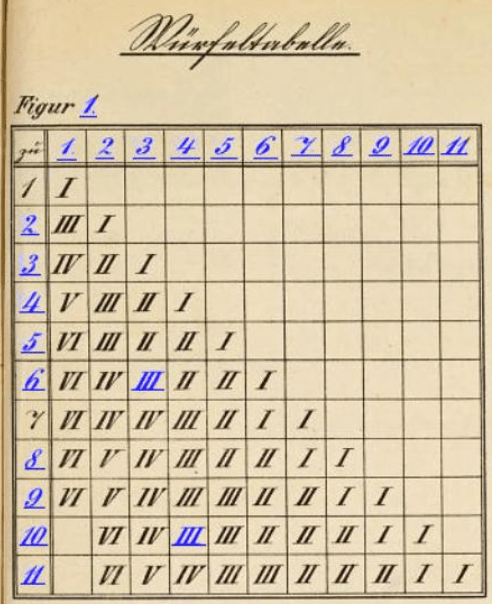

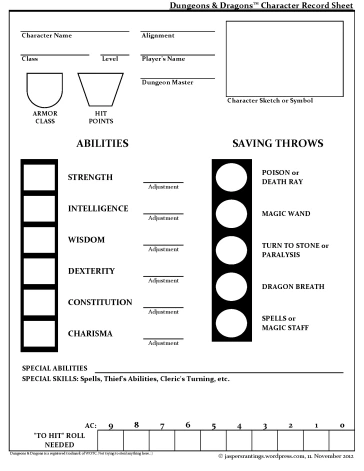

Some of the fastest prototyping you can ever do is analogue prototyping. Using wooden cubes, dice, and perhaps some printed cards or tables to represent dynamics you want from your systemic game.

What’s great about analogue prototypes is that you can represent complex processes using very simple mechanics. If you want a few different outcomes from a fight, for example, or want guards or animals or something else to behave intelligently, you can simply use another player to represent the choices they make. Give that player a card or sheet of paper that lists their options, and you’ll be able to try things out within five minutes.

You can make role-playing games that rely more heavily on imagination, or you can make playable board game prototypes. For same games, such as digital card games, you can prototype the whole game in analogue form and get a fairly accurate representation of how it’ll work once finished.

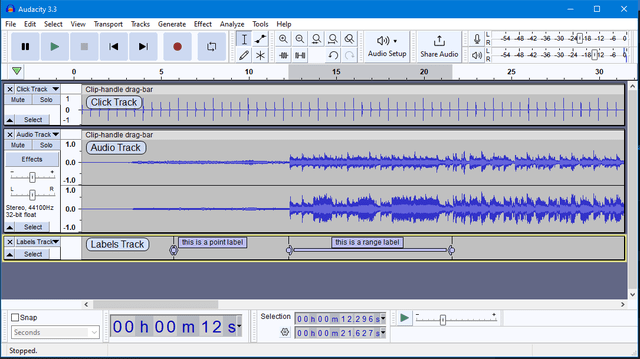

Prototyping

You can put something together in exploration that demonstrates a very specific mechanic and nothing else, or explores just a couple of different systems. What’s important is that you do not keep this around after it has proven what it was made to prove.

A throwaway prototype should never take more than a day to build. Preferably even less. On one project, I had an idea to make a camera that would automatically make sure that all important points of interest remained on-screen. My idea for doing this was to have the camera automatically keep a bounding volume’s min and max corners on-screen and to adapt camera placement and zoom if the size of this bounding volume changed. When points of interest were added or removed, the bounds would be resized to encapsulate all relevant points of interest.

This took an hour to write and demonstrated the idea. Whether it was successful or not was a discussion with the team. It still clearly demonstrated what I had in mind.

One reason to do things this way is that it’s not speculative. Even something obviously broken or half-baked can sometimes prove an idea, whereas a long meeting can’t really prove anything and more easily boils down into a polarised argument.

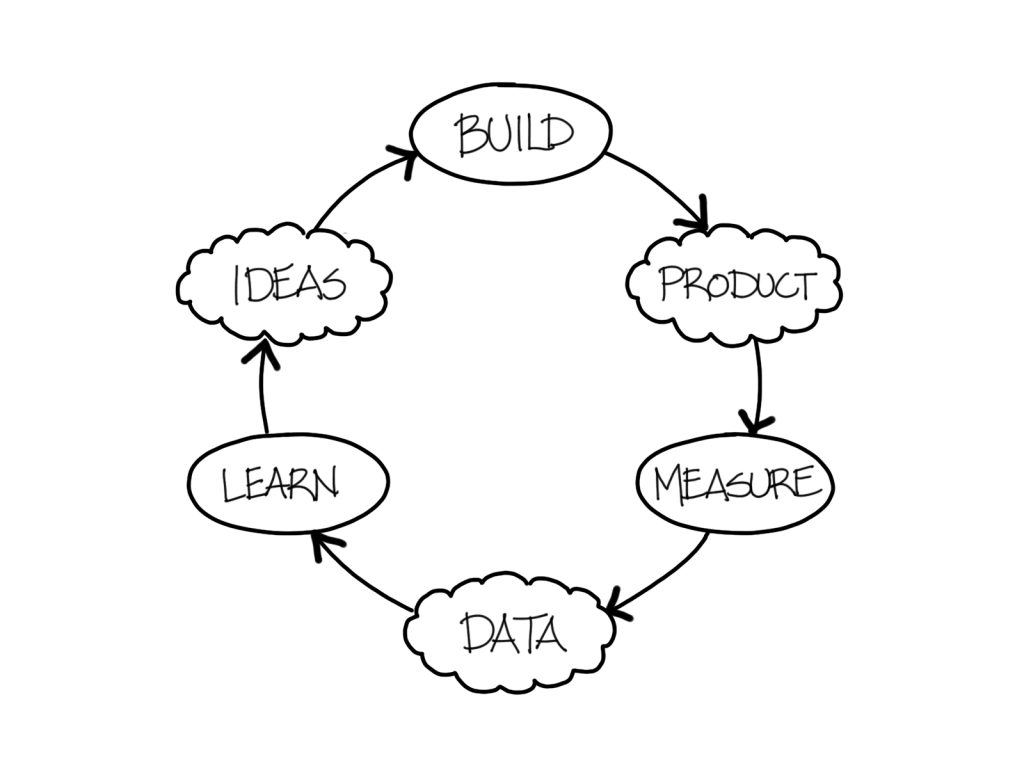

Have an idea? Try it, evaluate it, make a decision on it, and move on. This is what exploration is really about.

Proofing

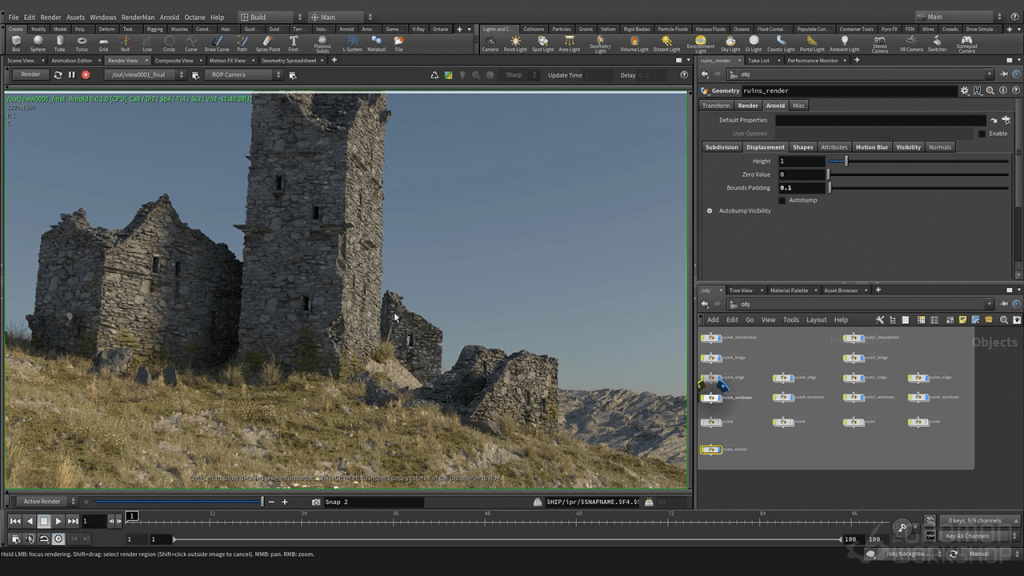

In printing, a proof shows you an accurate representation of how a design will look like when professionally printed. This is done to make sure that the material feels right, the colors look right, and so on.

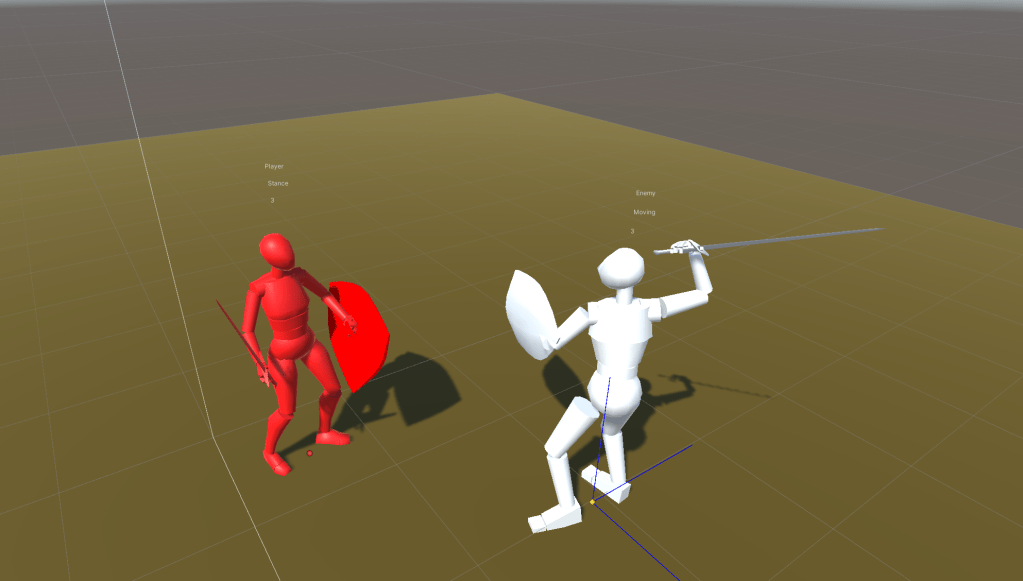

The same line of thinking can be applied to systemic design, where a proof demonstrates the validity of a specific system. You shouldn’t delve into the synergies or other properties of the system at this stage. Only the system itself.

If a system proof takes more than a week to build (maybe up to a month for something that’s bigger or more complex) you’ve probably moved into tooling or even production without noticing and should move on to the next proof. But before you move on from a proof, you need to agree on how and where it fits and also list all of the improvements you will need to make during production. This is where technical literacy becomes a prerequisite, because many of the improvements that are needed will be immediately obvious to the disciplines involved but can be deeply esoteric for everyone else.

Let’s say you’ve built an animation system and it’s working mostly as intended, but it still looks glitchy, doesn’t always transition as intended, and feet are sliding across the ground. Most of the solutions to these problems are self-evident, even if they will need work. At this point, you shouldn’t fix them. Not yet. Start building your production backlog, so you don’t forget them. That foot sliding will be handled using root motion and inverse kinematics on the feet, maybe. Note that down. Just don’t get stuck. You want to prove all the systems you have intended for your game before you can fully grasp what you are making.

Build a proof to “good enough,” then move on to the next one.

Merge Checkpoints

Because developers sometimes get tunnel vision and go on mental journeys both far and wide, it’s important to focus back on the product you’re making now and then. A merge checkpoint means a couple of weeks of putting everything done so far together into a cohesive whole. This exercise is always useful, and doing it semi-regularly is crucial to avoid project fragmentation during a long preproduction. It can also help avoid buildup of unnecessary technical debt, since unrelated proofs may start straying too much in different directions if they are left isolated.

The most important part of this, and why it needs to be part of exploration, is that it reminds you of the product you’re working on. It’s too easy in game development to get stuck watching nothing but what’s on your own screen.

Stage 3: Commitment

You will spend a lot of time bouncing back and forth between Ideation and Exploration, until you feel that you finally understand the game you’re building (or time runs out). Then it’s high time to commit to what you are making. To finalise your design.

When the commitment stage is done, you can never go back. What you’re committing to is the product that you will be building. There are many reasons to put a hard line between ideation/exploration and what comes next, not least of all that many game designers have a really hard time stopping.

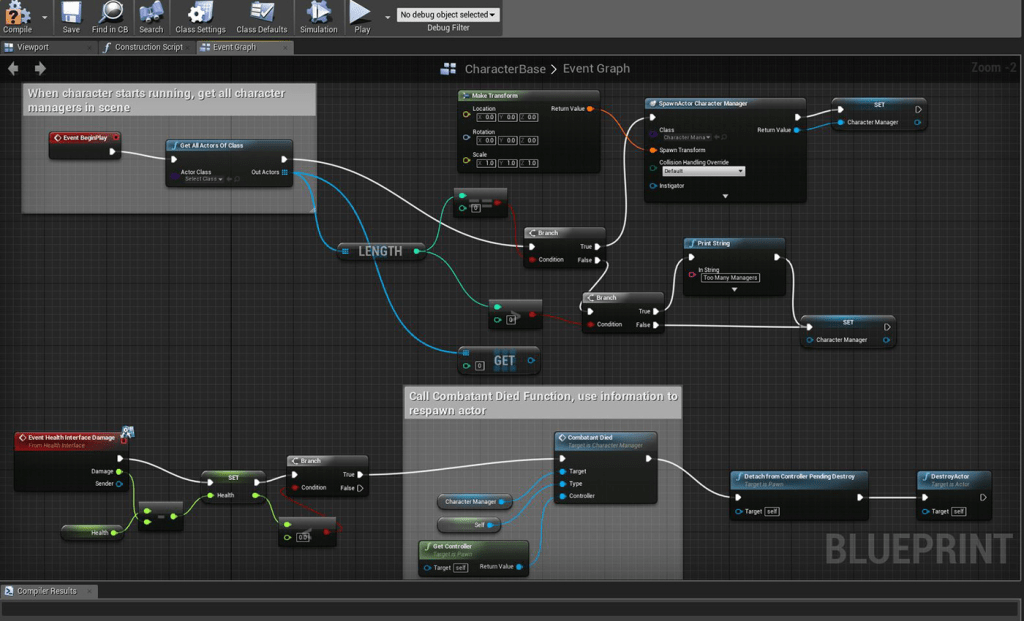

Facts

With prototypes thrown away and systems proofed, it’s easier to reach conclusions. The smallest possible unit of agreement is the fact, where we can say something like, “the player kills enemies using guns” or “the player character is a llama whose name is Lola,” because those are things everyone on the team has agreed on. But it needs to be specific enough to be workable.

Once your list of facts gets longer and longer, you’ll realise that you’ve suddenly designed your game one tiny incremental decision at a time. There will also be synergies coming up just from the associations you can make from individual facts.

Pillars

A pillar can be likened to an Internet meme. The idea is that you can have stated goals with your design that can be communicated across your team and used to validate every single decision that gets made. It can’t be too generic (“fast-paced”), but must be continuously reinforced and referred back to until everyone understands what it’s about.

Twenty (!) years ago, when we worked on a small school project, we used the term “high-tech low-tech” to talk about a science fiction setting where we’d mix Mayan influences with space ships. This meme stuck to the point that it almost became a joke, but that was good for the project since it meant everyone could align around it. So don’t feel bad if your cool grimdark design pillar gets laughed at. In fact, it can actually be even better than the opposite.

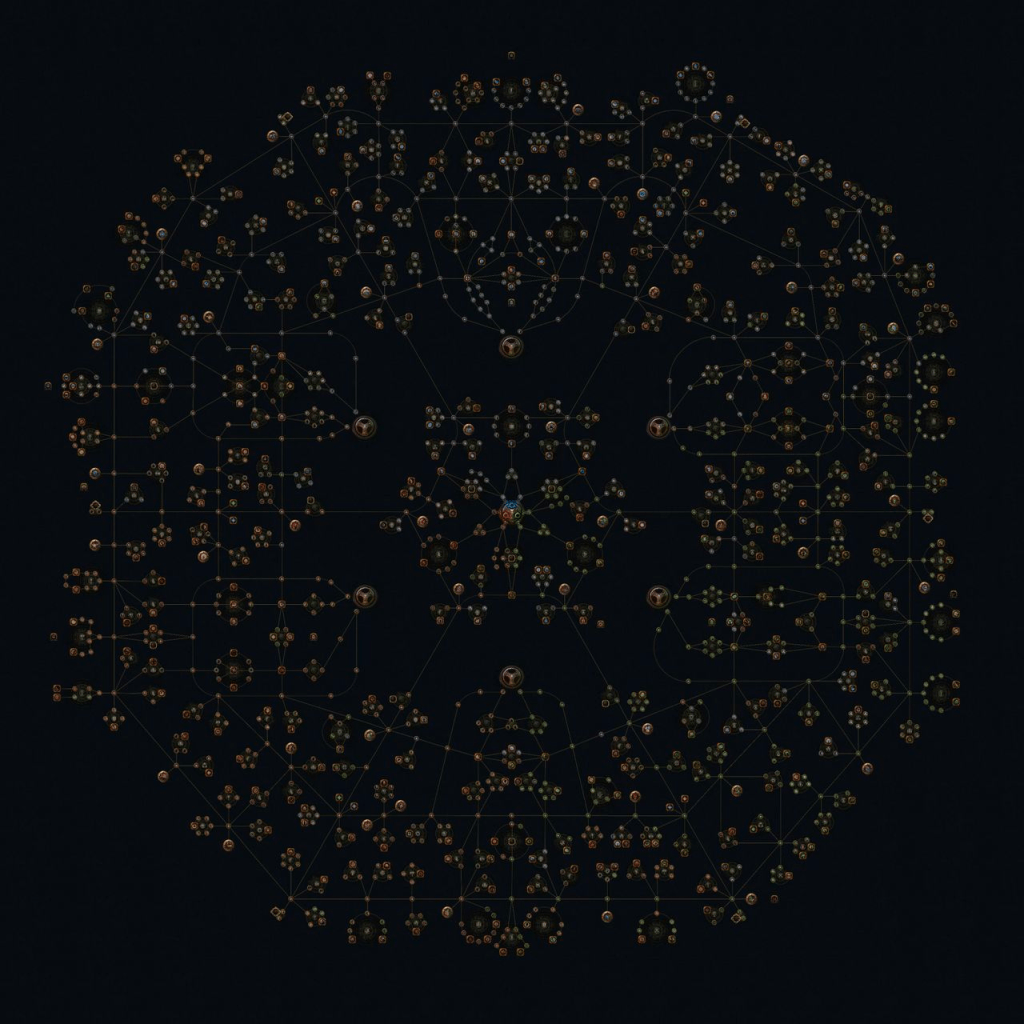

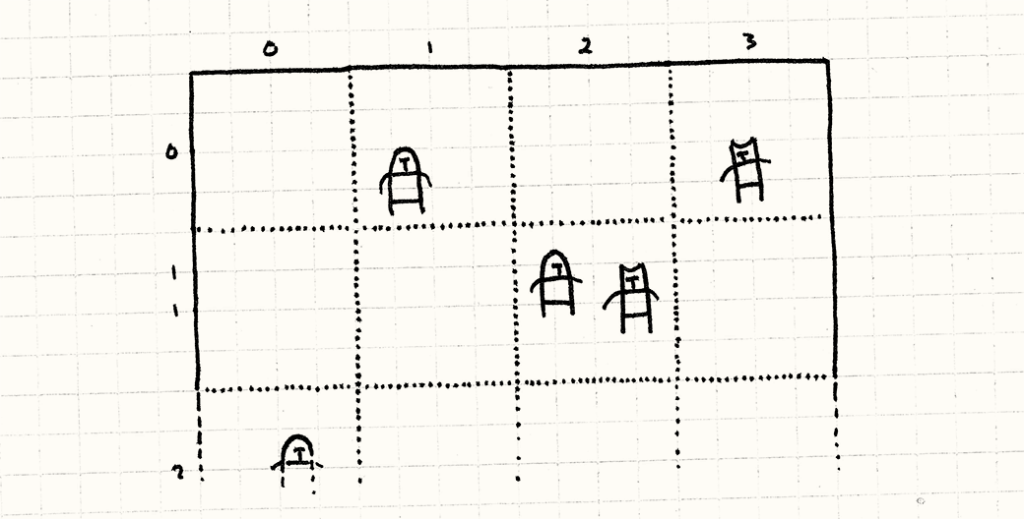

Object Map

These games are object-rich, as we know. A large part of systemic design is to be able to apply conceptual models to objects in a simulated world. To be able to do this, you need to map out all of the objects you will have in your game.

If you want, you can do a bit of object-oriented thinking here as well. Consider if something is-a or has-a. A goblin is an enemy, for example. The goblin also has a weapon, a helmet, and maybe a dream about retiring to live with their family on a remote farm some day.

You can also add some character and/or story context by adding what characters may want. This way, you will often be able to spot conflicts and the like completely naturally, or fill them in where they are missing. If only one character wants a thing, there’s no conflict there, so maybe you can just skip the thing or add conflict.

Just remember to keep things short and to the point.

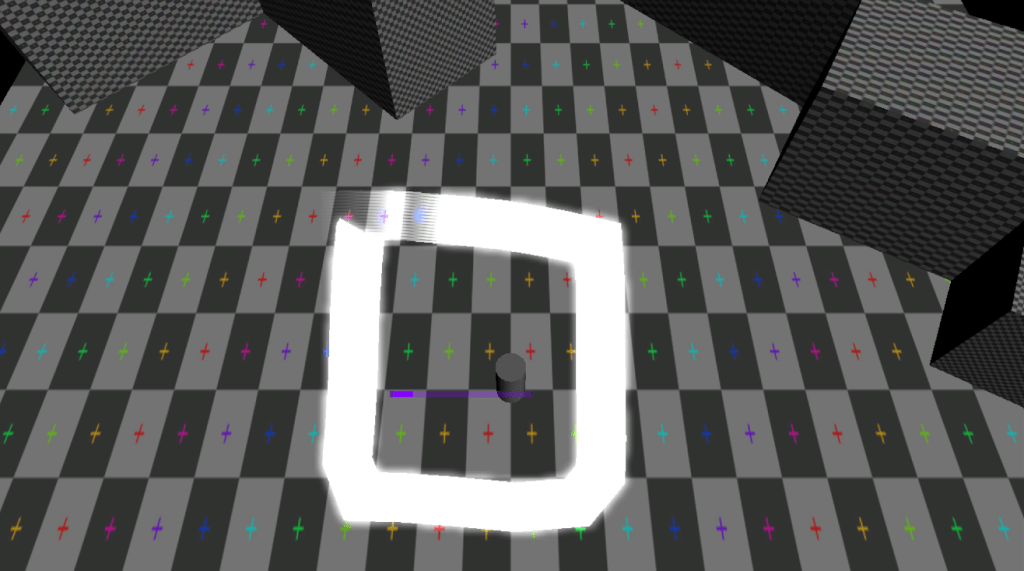

State-Space

With all of the objects mapped out, you can also map out all the states that these objects can be in. I like doing this as part of the prototyping, because it means both that I can respect encapsulation in code and that I can build things fairly rapidly. It’s also a good way to enable layering, so I can turn things on and off and test other things in isolation.

When you map a systemic game’s state-space, you can’t be too specific however. Leave room for inputs and outputs; allow the state-space to be flexible. For example, even if the player is in the Vaulting state as illustrated below, it should probably still be possible to get shot, hit by a trap, decide to fire a gun yourself, or whatever else the game may have on offer. You will start seeing many of these cases when you map your states.

Rules

With all of the exploration you’ve done by now, you should be ready to write out all of those permissions, restrictions, and conditions that we talked about. At this point in your exploration you know what your game is about and you know how this can be communicated to players.

A rule can be, as was alluded to previously, “you can always fire your weapon.” Clever readers among you will of course understand that this is really close to a fact, so the first thing you should do when you try to finalise your game’s rules is to go through all of your facts and see which ones are also rules. Some of them often are.

The difference is that a fact is merely an agreed-upon thing in the game design, while a rule is something we need to teach the player. A player-facing fact, in a way.

Possibility Space

With the object list, state-space and rules designed, you will see the full game emerge. What can be called the game’s possibility space is the combination of the rules interacting with all the objects and their states. Since we’re about to commit to this game and push it into production, it’s highly likely that you will want to control this process.

For example, “you can always fire your weapon” clashes with the two-handed carry heavy object state. Also, something needs to happen if you don’t have a weapon and try to fire it. In many of these cases, you will want to make exceptions. They can be for visual reasons, for example that it doesn’t look good to have someone fire their pistol while carrying a heavy object. It can also be for reasons of “nerfing,” and that you feel it will become too good or not good enough.

But here’s a crucial truth with systemic design: you need to let go of this authorship. Let go. Let the possibility space be an amorphous thing that you can’t quite control, because it’s the players who should be having the fun.

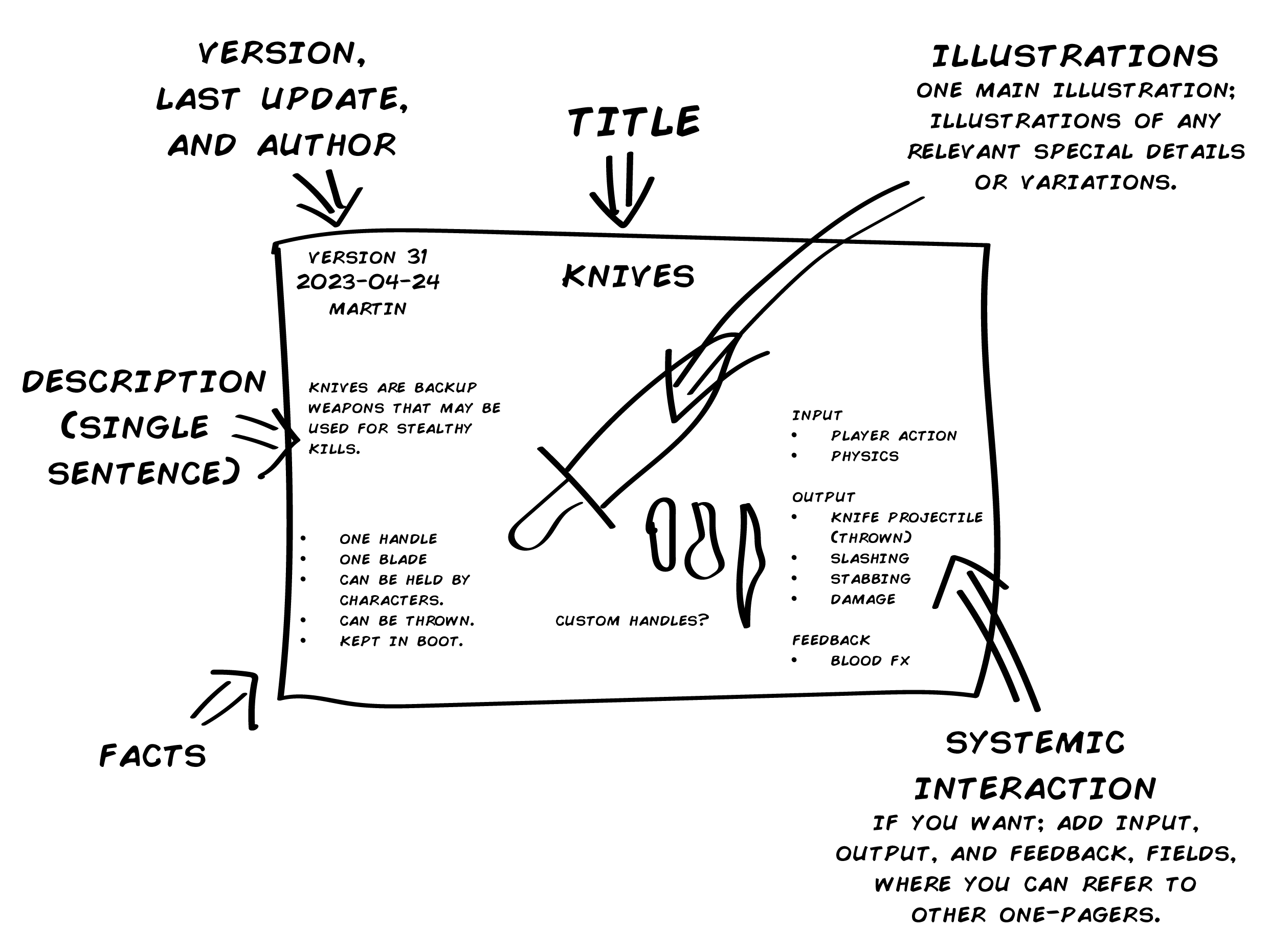

One-Page Designs

One of the best game design talks I’ve ever seen is Stone Librande’s talk on one-page designs. For systemic design, this pairs incredibly well with Aleissia Laidacker’s talk on systems if you want even more background for how this all comes together.

This is, finally, what your output should be at the commitment stage. You should write one one-pager for each system and for each component, rule, and so on, until you’ve covered all of the facts, resources, inputs, outputs, and feedback hooks in your game design.

While writing one-pagers, it helps to establish a standard. Maybe you’ll capitalise words to show that those words are the headlines of other one-pagers. The neat thing about this is that you can quickly iterate on your one-pagers down the line, by simply bumping up the version number and/or update date and replacing it with the new one. By keeping every responsible developer referenced on the one-pager, you will also facilitate information sharing and work process.

I personally swear by one-page designs, but it’s really important that you don’t rush into making them. Do the ideation and exploration properly, then you can sum it up as one-page designs.

One nice touch to make it more visible when something is changed is to add a colored line to the edge of a one-page design paper each time it’s upgraded. This way, people can quickly see that the previous one-line design suddenly has two lines and that they should take a new look.

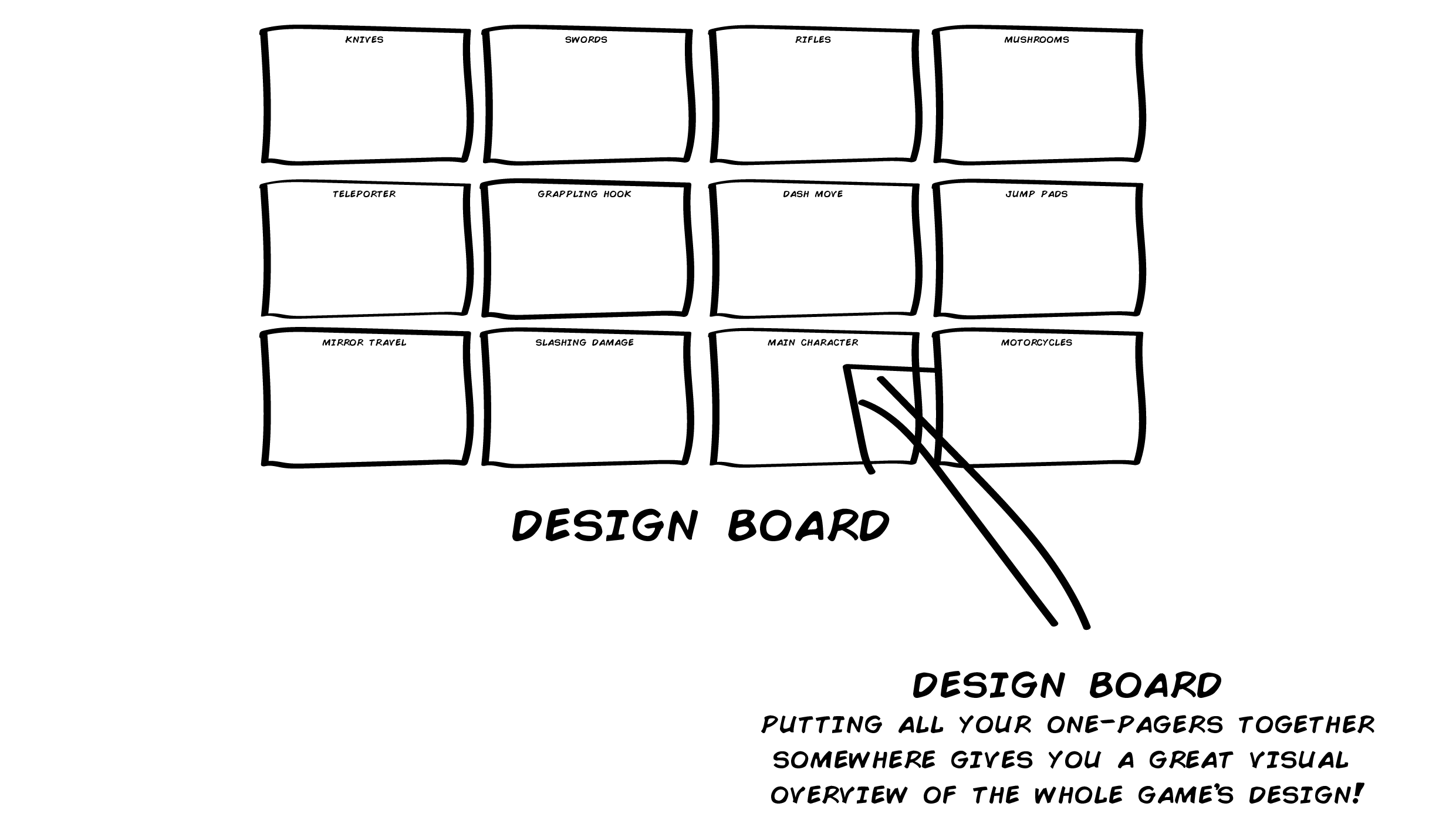

The Design Board

A design board is a whole mosaic of one-page designs that describe all object interactions in your game. It can be added to, updated, and used as a live document more easily and much more visibly than most other methods of immortalising game designs.

In an ideal world, you can have all of the one-page designs printed out and placed on a wall somewhere, but something like a Miro board is often more practical.

How you place your designs on a board is a science in itself, since the relationship between one-page designs isn’t always clear-cut. If you have Prop as a design, and Weapon is a type of prop, how do you then place the Rocket Launcher that both is a weapon and spawns rockets that are potentially also pawns?

As with so many other things in game design, how you prefer to organise your design board will be up to preferences, space, and some experimentation. But once you have this board completed and you feel that everything is present that will be a part of your game design, you’re done committing, and it’s time to make and deliver this game of yours.

Next Steps

The savvy reader will notice that we’re only covering the first three of the six stages. We’ve talked about letting go and learning to love it, and we’ve gone through a whole slew of terminology that will aid you in designing systemic games.

Unfortunately, there are no shortcuts for the next step. To learn how to make systemic games, you must make systemic games. Designing, planning, and finishing systemic games. I will get into the delivery aspect of this process, and the three remaining design stages, in a future article. But for now, you need to get out there and make systemic games.

Unless you send me an e-mail at annander@gmail.com and ask to pay me to do it for you, of course. Or simply to tell me how wrong I am. But I want to play more systemic games, so hopefully you’re now running off to make them!