Systemic design comes down to making objects and rules and inviting the player to interact with them. This sometimes clashes with game design at large or the expectations of external stakeholders. This post is dedicated to some challenges that are facing systemic game design right now.

It won’t go into broader problems like financing or marketing — not in this post. This one is focused on design.

I would also love to hear about the challenges you are facing, as a comment or to annander@gmail.com.

Overcoming Recency Bias

Indie game developer Mike Bithell once tweeted that game design tends to favor the past five years’ most prominent hits. I’ve tried to put this in context in the past, writing about different broad “eras” of game design, but this is a considerable challenge for game design overall. Maybe the biggest one. Recency bias is one of the root causes for many of the other challenges described in this post.

The only way to overcome recency bias and broaden your personal references for games is to play games from different eras. To push yourself out of the five-year recency bias. Playing games from genres you don’t normally play and engaging with games and gaming positively rather than through hearsay or preferences.

Play lots of games and you will find both gems and turds along the way. Over time, this will make you a better game designer. Allegedly, Quentin Tarantino used to watch around 200 movies per year. Maybe as a designer you should take 30 minutes every morning to just try a game you wouldn’t normally play. Like a concept artist doing warmup sketches. Eventually, you’ll at least try as many games as Tarantino watched movies, and this will broaden your frame of reference.

Avoiding Reductionism

Call of Duty, which is a first-person shooter, has a sprint button that boosts your movement speed; therefore a game cannot be a first-person shooter without a sprint button.

This line of reasoning is design reductionism. Portraying a thing as represented by a specific part, thereby reducing the thing to this part. You can extend the same kind of argument to almost any genre or game, and sadly this is very common.

Many discussions on definitions in game design become reductionism. Not always intentionally, but whenever we say “X is not a Y because it doesn’t Z,” we’re falling into this particular trap.

Two ways where reductionism become game design obstacles are as denial and as obligation. X doesn’t have the feature, so we shouldn’t have it either; or, X has the feature, so we must have it too.

One way to avoid reductionism is to remember the Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics (MDA) framework and its conceptual division and to categorize what you may be reducing accordingly.

If you look at sprint in Call of Duty (CoD) as a mechanic, for example, the running for cover to regenerate your health is the dynamic it leads to in combination with other mechanics. This means that a game that doesn’t have the regenerating health or even any cover to run for doesn’t benefit as much from a CoD-style sprint mechanic. If you borrowed only the mechanic, expecting the dynamic, you’d be disappointed.

Playing Less Reference Tennis

Since we don’t really have an established language around game design, and genre definitions lack unanimity, references to other games easily becomes the only common ground we have. But this easily leads to “reference tennis,” where you are bouncing different game references back and forth until someone mentions a game the other party isn’t familiar with, thereby dropping the ball and either ending the conversation or conceding it in some direction. This is not conducive of constructive design work. It’s often the worst possible kind of reductionism, or it’s simply a game developer form of might makes right.

Avoiding reference tennis and designing by reference requires that you move the conversation to your own game. This is where game design pillars, established facts, and a playable game with clear problems that require solving come in.

Actively avoiding references to other games during a game’s earliest design stages is the best way to try to build confidence in your design. Describe the experience, the emotions, the themes and mechanics; just don’t use other games to describe them.

There’s little use in trying to boil something as complex as a video game down into a single hook or elevator pitch line, because this often forces you to say something like “the mechanics of X plus the art style of Y,” and that will have as many interpretations as it will have listeners.

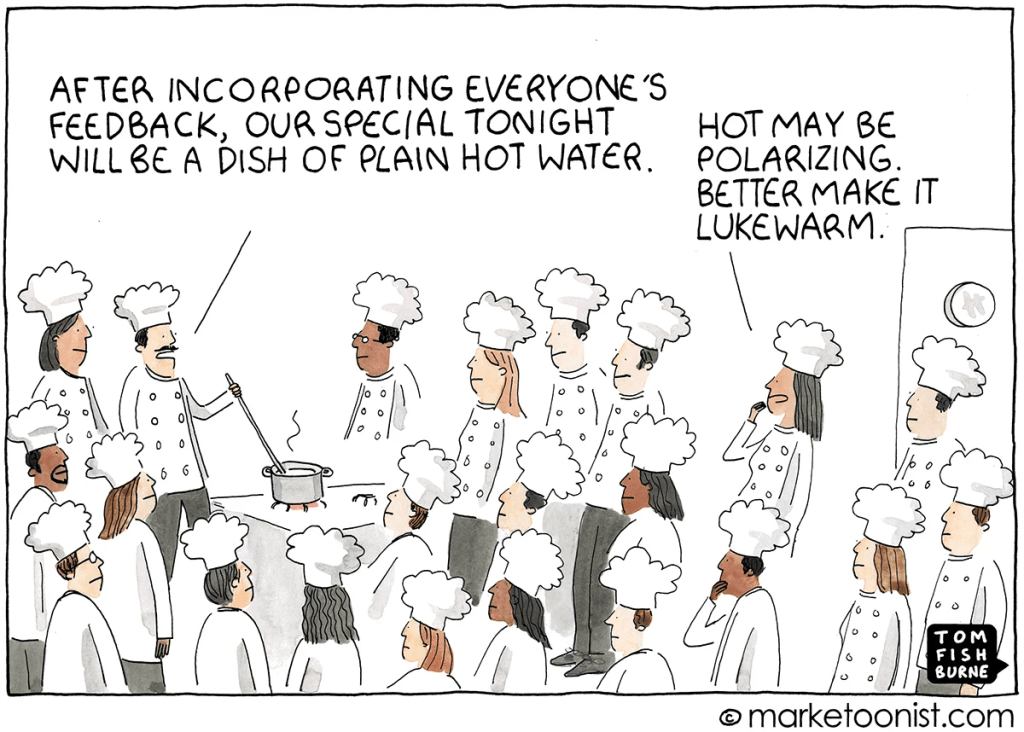

Disbanding the Design Committee

Designing by committee is where no one dares to have a vision and everyone defers to everyone else. It either leads to no decision-making at all or to decisions that are as vanilla as they can be so that no one in the committee risks feeling sidelined.

As a colleague liked saying, it’s the heat and the pressure that makes the diamonds. Creative discussions, constructive disagreements, making things someone feels strongly about, and scrapping things that didn’t work out even when someone did feel strongly about it. Game development can’t afford fragile egos and also requires a diversity of skills that makes it a poor fit for auteur directors. Put a bunch of experts in a room and let them be experts.

In reality, the only way to disband the design committee is to find people you can talk to and work with in an open and constructive manner. People you trust and who trust you. It also helps to have a clear vision, with the already mentioned pillars, facts, etc.

Stop Chasing Trends

Making a game that is in one way or another extremely close to something already on the market can be an efficient way to make a buck or two. Not always, of course, but the number of games that carry a World of Warcraft painted aesthetic, make use of extraction shooter mechanics, or strives to be another roguelike, Minecraft, or deckbuilder speaks for itself.

Like reductionism, this often comes from risk aversion. If you see someone else demonstrating the success of a thing, you imagine that you can skip directly to the profits by making a similar thing. This is sometimes called the packaged goods model, where marketing is functionally more important than the product being marketed. Coca Cola vs Pepsi marketing often tries to sell an identity more than a beverage, for example.

But games are not packaged goods. Games are creative products where gamers can express themselves through play or experience something outside of themselves. Gamers are also highly likely to vote with their wallets if you only give them something that is a repackaged version of something else. Some trends die faster than they appear, and it’s hard to know this before you get started.

Considering how much business in game development that is handled by people from packaged goods industries, this issue is probably not going anywhere anytime soon. But please, as a designer, try not to chase trends. You don’t have to make the next extraction shooter survival game.

Don’t be an IP Tourist

When Kane returned in a coma with that thing clinging to his face, you had no clue what it was. It frightened you nonetheless. Its strangeness, its alienness, frightened you.

But that terror can’t be replicated anymore. We’ve labeled the creature a “facehugger” and made it available as plushies, on mugs, and adorning the jewel cases of the special collector’s edition DVDs we hold on to but haven’t watched for fifteen years.

Yet, more Alien-branded games are made. More scenes with facehuggers are featured, often predictably. It’s no longer a creative choice, it’s a must-have. Something to check off a list when we’re on Alien safari. Android, check. Distress call, check. Facehugger, check. It’s the same when characters in The Mandalorian keep joking about how bad Storm Troopers are at shooting. That was never a joke: it’s something the fans made fun of. To the Storm Troopers, what they are doing is real and most definitely not a joke.

All of this is IP tourism. It adds nothing new, it doesn’t contribute anything. It only repeats the key selling points of a franchise either as fan service or as a lazy attempt to retain an existing audience by using self-referential in-jokes that only the “real fans” will get.

In my opinion, the best games in the Halo franchise were Halo: Reach and Halo 3: O.D.S.T, simply because they did things that weren’t just IP tourism but took the IP to new places and painted the war against the Covenant in a different light. We didn’t need more Master Chief, even if the original games set the stage, and we got the Fall of Reach story and a noirish detective story with Halo framing instead.

If you ever have a chance to work on a cool IP, don’t be an IP tourist. Build a real experience that explores that IP in some way.

Make Decisions Matter

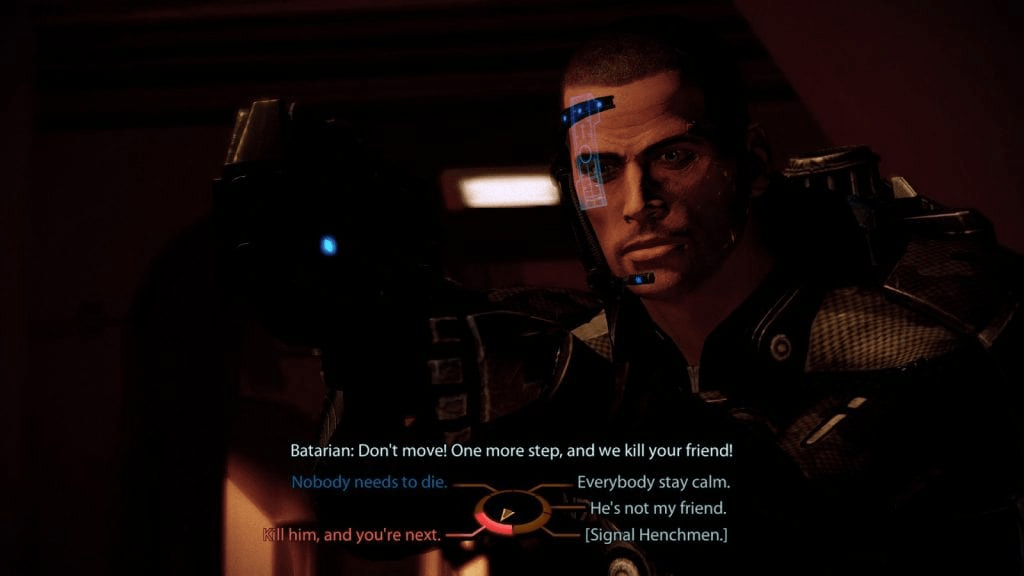

The key to Sid Meier’s classic statement on decisions is the word interesting. A game is a series of interesting decisions. If you remove the emphasised word and the player is making decisions that were all created equal or from only partial information, then the player no longer has any meaningful decisions to make, they are just along for a ride.

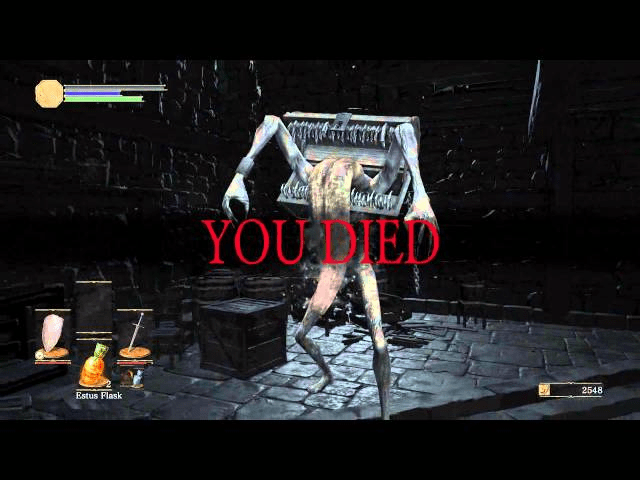

I always felt that the style of choices you made in series like Mass Effect were this type of choice. You could choose to be altruistic or evil and you’d get an immediate often spectacular response, but the longterm effects were usually not that relevant. From your own intentions, you could end up making a right or wrong choice, but it would often be either completely obvious or entirely opaque and you’d be picking mostly as a gut reaction. Someone dying in a cutscene at the end of the game isn’t the consequence of an interesting decision, it’s just a shallow reminder that a decision was made.

If you are interested in a deeper take on choices and consequences, you can watch Bob Case’s excellent video on the subject. To me, this is where systemic design truly shines, as interacting systems will be restricted more by which inputs and outputs you allow than by content.

Focus on Art Direction over Fidelity

Remakes have always been a thing in video gaming, ever since the early days. But a trend that may have started with the Halo: Combat Evolved Anniversary Edition remake and that deeply affects game design is to take a game and increase its visual fidelity to a modern standard without considering the core art direction of the original game.

To contextualize this a bit, production pipelines for video game graphics were revolutionized in the early 2000s with the gradual but widespread introduction of Physically-Based Rendering (PBR). The techniques were described in the 1980s, but what set this off for games was partly a book by Matt Pharr, Wenzel Jakob, and Greg Humphreys (link is to the table of contents for the 2023 edition).

Before PBR, much work with textures had to be manually tweaked until it looked right. With PBR, artists could start relying on real world measurements and assign material properties that always provide realistic results.

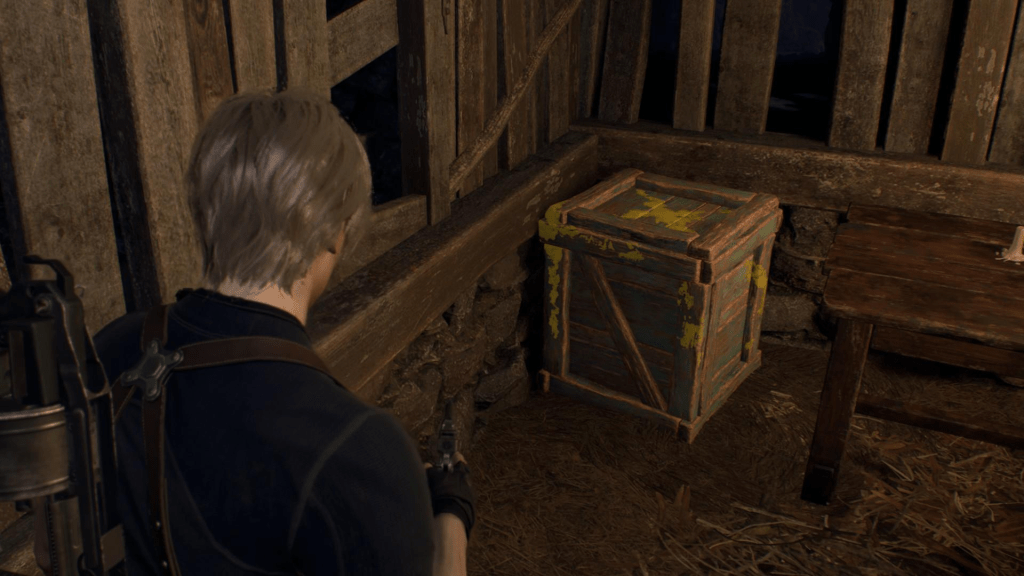

What many 3D remakes then do is that they take a pre-PBR 3D video game and they remake the visuals for PBR. A realistic look from a purely practical perspective, but also one that doesn’t respect the original often carefully crafted art direction.

In a pre-PBR game, the environment and interactive objects could be designed to read more easily. In remakes with full PBR and high resolution textures, everything looks the same. More often than not, you need to compensate for the loss of art direction, for example by using dabs of contrasting paint to highlight what the player can interact with.

Two things to note is that this in no way means PBR is bad or that it shouldn’t be used, or that this is limited to remakes. All it does is that it shows you how tricky it is to match game design and art direction when all you are doing is making something look “more realistic” by increasing fidelity. Movies, which are filmed in the actual real world, very rarely focus on looking realistic, but will instead use lighting, composition, and other techniques to make sure that the right information comes across.

Allow art direction and game design to inform each other, and please stop letting whoever paints all the yellow paint have all the fun before the hero even gets there.

Stop Commodifying Player Imagination

We can look at old school gaming — as far back as hex and counter wargames — as fantasy systems. Our imagination takes the output of dice rolls and table results and conjures up fantastic chains of events. Like how you can imagine the anti-tank crew in a game of Advanced Squad Leader sit there and whisper hoooold to each other in Mel Gibson fashion while you, the player, are hoping that the tank will move one more hex so your chances of hitting are increased before you tell your opponent “I shoot!” All of that tension is a natural and emergent effect of the game’s systems. The actual physical experience of playing the game is just a bunch of cardboard counters and dice.

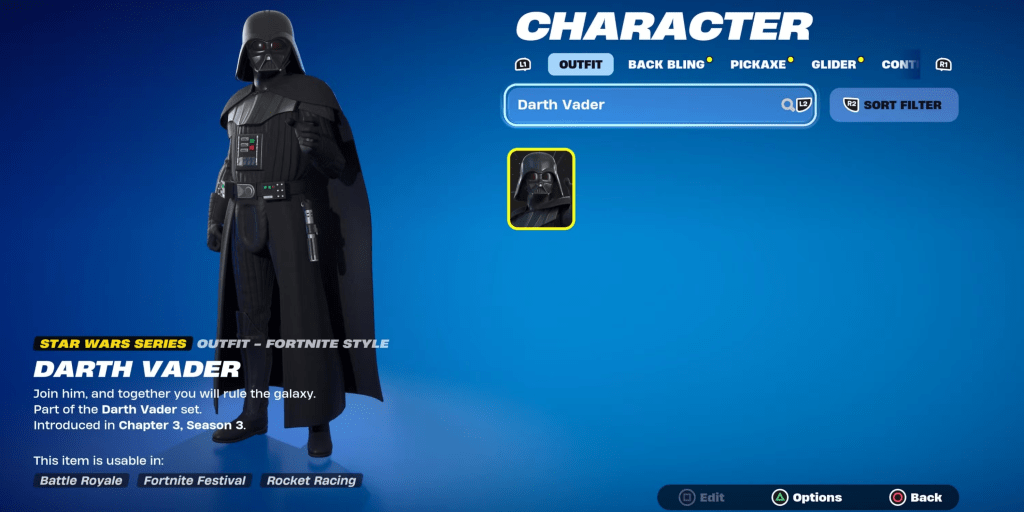

Player imagination is the most powerful tool in a game designer’s toolbox. Yet, in many types of games, the design doesn’t really allow it. Instead, we sell you the permission to imagine things and actively restrict you to only imagine things we can charge money for. The official experience.

You won’t find freeform customization as often as for-purchase skins of popular characters. The workings of our fantasy systems are paywalled, and there will always be a next purchase for you to make if you want to satisfy that fantasy you had in mind. Be it the all-black gothic armor set or the bladed boomerang or something else that you didn’t actually want or need.

Players are creative anyway, of course. They will always draw penises if you give them half a chance, and some can spend hours in your character creator to imitate their favorite celebrity. But the reason this is a challenge for systemic design is that the official allowed content that we sell is never going to be half as cool as what players can discover on their own if you let them.

Facilitate player imagination, don’t commodify it.

Use Technology to Solve Problems

Generative AI has been saved for last, because I’m not personally that worried. If people can find inspiration from a ChatGPT chatbot or get past programming obstacles that are hindering them in their work in some way thanks to some flavor of Copilot, then that’s great. Use the tools that make you more effective.

But one thing is problematic: people’s faith in Large Language Models (LLMs) and other black box technologies. How people from outside the industry can come in and tell us that hey, you can use AI to make your enemies smarter or to write dialogue for you. Because yes we can, and we’ve been able to for decades, but we shouldn’t and we won’t. The amount of text that we put into our games has never been the problem, and having to expensively teach our enemies how to do actions we could much more easily build systems for is a bottleneck more than a solution.

To make more dynamic and responsive games, we don’t need a new black box, we need to develop the paradigms around how we think and design. We need to design games in more systemic ways. Complex systems start from simple systems that work — they are not made out of black boxes. LLM technology, Machine Learning, Reinforcement Learning, and much more, are useful algorithms that we should put to good use when they solve problems for us. But only then.

The best stuff we can get out of the LLMs probably hasn’t appeared yet, and it won’t do so until we get past the stage of overhyped excitement that seems to dominate the tech space today.

Solve problems, don’t buy into hype.

Complete disagree on the Reference Tennis part, especially for a Systemic Game.

Why read a Book and learn from them when you can Remain Ignorant?

What people don’t understand is Systems are actually Genres.

Genres are already successful implementations of Systems that are know to have Depth and provide Gameplay.

You need to know the Best Games in a Genre to look at how they implement their Systems, as well as additional games in a Genre to Contrast and Compare on diffrent implementation of those Systems.

I can tell you right now that without understanding Patrician, Anno, The Guild you will never fully understand how to implement a proper Economy System.

I can tell you right now without understanding Kenshi, Rimworld and the 4X Genre you will not understand how to implement Dynamic World Simulation with Factions and NPC simulation.

For Goals and Domains that you are meant to Research you better do your Homework, those who don’t aren’t even on the starting line and part of the discussion on working on those Goals and Domains.

Especially for Systemic Games that are so hard to understand and with the pretty nebulous existence of “Emergence” that is ultimately a side effect between systems, you cannot afford to lose any knowledge, insight and interaction between systems.

Ignorance is not Strength.

Playing and understanding more games widens your frame of reference; I completely agree that this is essential for any game designer. The harm is when you describe *your* game by using references to other games, or when you copy mechanics expecting dynamics. I’ve worked in several teams where reference tennis was problematic simply because whoever “dropped” the ball would lose the conversation. If you didn’t play the referenced game, or had a different opinion about it than the person speaking, you could no longer take part in the conversation.

Play games — as many as you can. But before you dig too deep, you need confidence in your own project, or the risk is that you’ll just make a worse version of something better.

I also disagree that there are any mandatory games for understanding certain dynamics. There are countless ways to do the same things in game design, and no be all/end all solutions.

“Explaining” things is completely useless.

You can have tons of documents and articles explaining things and people still won’t get it.

The only way to UNDERSTAND things on a Deep Level is to actually to Play It.

This is why Game Design Documents are useless on some level and you need actual Prototypes.

Those who do not get the references are simply Not Part of The Conversation, they never were and they never will unless they play it, let them do their job and play it or shut up and do what they are told.

It’s not the people that play games that have a more limited understanding on how things work. It’s the developers that copy without playing it that fail at that.

There is a reason why Expert Players of a Genre have their weight in Gold, they are the ones who understand the Deep Problems and Limitations of that Genre much more than developers that have a more shallow understanding of it.

They tend to be the Modders that can actually fix problems and balance issues.

Ignorance is not Strength.

And You Do Not Know What You Do Not Know until you find out for yourself the reason Why I said all that.

Try it for yourself, find the reason why I mentioned those games without playing them and then play them and see the difference.

People forget that Games are Holistic, sometimes you get more than the sum of its parts and you won’t understand that if you just learn the pieces.