“We’re making an ARPG with survival and roguelike elements,” begins the pitch. “It also has some light platforming, is made with Godot, and intented for release on Steam in Early Access.”

For the business-minded person in the crowd who just played Path of Exile 2, they may focus on the ARPG bits or conjure up mental images of lucrative microtransactions.

One who recently finished Subnautica may catch on to the survival bits, for good or bad.

One who bounced off Hades 2 for some reason could be negative about the roguelike element.

Another may latch on to the idea of platforming and think that there’s no point to go up against some other popular platforming game that’s about to hit stores around the same time.

Someone may dismiss it simply because they said “early access,” or because they have opinions on the choice of engine.

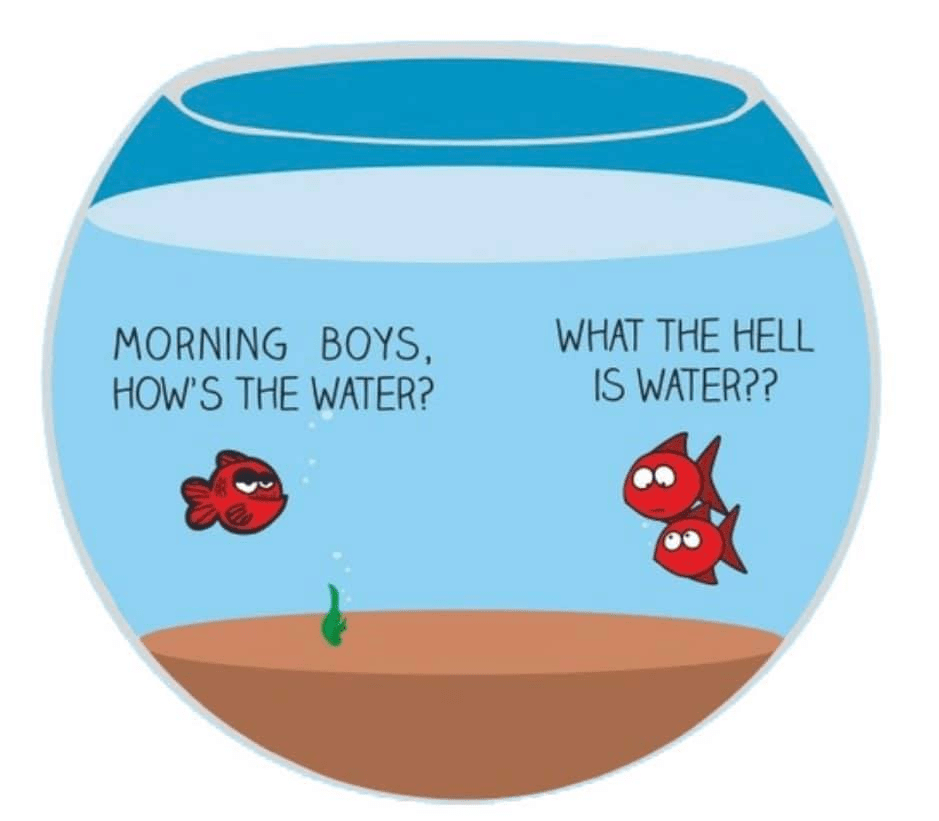

This pitch has managed to confuse everyone in the room, using seemingly standard terms. The genres and abbreviations we take for granted seem just as watertight and solid as any formal academic definition, but they really are not.

In fact, I want to argue that attempts at general definition harms game design. Definitions can and should change from one game to the next. Asking someone to define something in general terms derails the creative conversation we could be having instead.

Let’s look at definitions of game design, to hash out what I’m trying to say. And as usual, if you disagree, please do so in comments or to annander@gmail.com.

We Have No Words

Why is there no definition of game design? In fact, the definitions are legion. We simply can’t agree which one to use. Not even at the university level. Faculties across the world use different ways to talk about game design. One university may talk about game design as level design, while another involves scripting, and a third uses boardgame design as the springboard.

So let’s look at some ways that great game designers have tried to concretise the language around our work.

The Art of Computer Game Design

“Creativity is concerned with the invention of something new and different,” said Chris Crawford in 1989, in his famous ‘whip speech’ at the Computer Game Developers Conference. I was seven years old at the time, so can’t say that the prospect of developing games had had a chance to form yet at the time, but it’s an incredibly inspiring talk to watch today.

But before wielding a bullwhip on stage, Crawford also wrote one of the earliest and most lucid texbooks on game design, The Art of Computer Game Design, published in 1984. A book that thinks a game needs three things: representation, interaction, and conflict.

Representation

“[A] game is a closed, formal system that subjectively represents a subset of reality,” writes Crawford.

Closed: “By closed I mean that the game is complete and self-sufficient in its structure. The model world created by the game is internally complete; no reference need to be made to agents outside the game.”

Formal: “By formal I mean only that the game has explicit rules. There are informal games in which the rules are loosely stated or deliberately left vague, but such games are not typical.”

System: “The term system is often misused, but in this case its application is quite appropriate: a game is a collection of parts that interact with each other, often in complex ways. It is a system.”

Subjectively represented: “Representation is a coin with two faces: an objective face and a subjective face. […] The distinction between objective representation and subjective representation is made clear by considering the differences between simulations and games. A simulation is a serious attempt to represent accurately a real phenomenon in another, more malleable form. A game is an artistically simplified representation of a phenomenon. The simulations designer simplifies reluctantly and only as a concession to material and intellectual limitations. The game designer simplifies deliberately in order to focus the player’s attention on those factors the designer considers important.”

Subset of reality: “[N]o game could include all of reality without being reality itself; a game must be, at most, a subset of reality. The choice of concerns within the subset provides focus to the game.”

Interaction

Game design concerns itself with all of these elements. But Chris Crawford also define games by what they’re not. “Games provide [an] interactive experience, and it is a crucial factor of their appeal.”

Games Versus Puzzles: “Games can include puzzles as subsets and many do. Most of the time such puzzles are a minor component of the overall game, because a game that emphasizes puzzles will rapidly lose its challenge once the puzzles have been solved.”

Games Versus Stories: “A story represents a series of events in a time-sequence that suggests cause-and-effect relationships. […] One important difference between games and stories is that a story presents its facts in an immutable sequence, while a game offers a branching tree of possible sequences and allows the player to make choices at each branch point and thus to create his own narrative.”

Games Versus Toys: “Games lie between stories and toys in manipulability. Stories do not permit the audience to control the sequence of fictional events. Games allow the player to manipulate some of the facts of the fantasy, but the rules governing the fantasy remain fixed. A toy is much less constrained; the toy-user is free to manipulate it in any manner that strikes his fancy.”

Conflict

“Conflict arises naturally from the interaction in a game. […] If the obstacles are passive or static, the challenge is a puzzle or an athletic challenge. If the obstacles are active or dynamic, if they purposefully respond to the player, the challenge is a game.”

If an “intelligent agent” is trying its best to stop you from succeeding, reacting to your interactions, it’s a game. “A game, then, is an artifice for providing experiences of conflict and danger while excluding their physical realizations. In short, a game is a safe way to experience reality.”

Crawford’s book is well worth reading still to this day. Though its examples may feel dated, what was true for Star Raiders is still true today. Unfortunately, like an example of how much game design knowledge has been lost through the years, few game designers use these terms today.

Formal Abstract Design Tools

One game designer who discussed the lack of a shared game design vocabulary early on is venerable Looking Glass alum Doug Church in his essay, Formal Abstract Design Tools, from 1999. This essay takes an example game — Super Mario 64 — and extracts “tools” from its design that can then be used more generally.

The first tool is Intention: “Making an implementable plan of one’s own creation in response to the current situation in the game world and one’s understanding of the game play options.” This is a seemingly clear device that defines how Super Mario 64 plays.

The second is Perceivable Consequences: “a clear reaction from the game world to the action of the player.” Another strong staple of Nintendo games in general.

What’s important to note here is that these tools are examples of what you can take with you from another game. In the essay, they are then applied to other games theoretically. You can certainly use them if you want to share some of the design sensibilities from Super Mario 64 with other games, but the point is to show you how Formal Abstract Design Tools can be devised and used across game design to generalise concepts that games can share.

This is further illustrated by the tool Story: “The narrative thread, whether designer-driven or player-driven, that binds events together and drives the player forward toward completion of the game.” A tool that can easily be generalised, and also serves as a reminder that stories drive the player’s motivation.

What’s fascinating with this essay is that it’s a framework and conceptual starting point. It even states directly that “this article was not intended to be exhaustive or complete,” and that “[i]t’s a justification for us to begin to put together a vocabulary.”

Still an insightful essay, and could’ve been a starting point for real work in this area, but now instead serves as a reminder that we’re several decades further along and still haven’t figured out how to talk about game design. The quest for abstraction was never completed.

MDA Framework

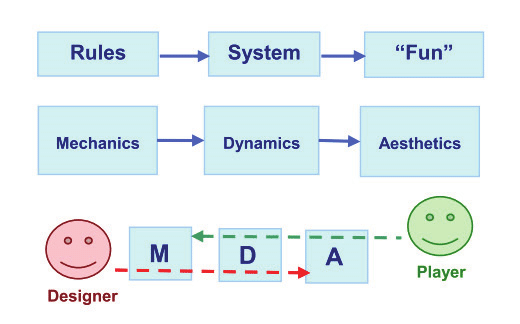

The next design treatise is often referenced by game educations, and it’s the MDA Framework, where MDA stands for Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics. The paper itself was written by three game design heavyweights, in Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek, and was developed between 2001 and 2004.

It begins with a lofty ambition:

“We believe this methodology will clarify and strengthen the iterative processes of developers, scholars and researchers alike, making it easier for all parties to decompose, study and design a broad class of game designs and game artifacts.”

There are a few key concepts in the MDA framework that are not too dissimilar to Doug Church’s sample tools. One is that “the content of a game is its behavior — not the media that streams out of it towards the player.” In other words, games are “systems that build behavior via interaction.”

This is a foundational assumption. Many types of games are bought, played, and then shelved as completed (or not) by their players. Those types of experiences are not what the MDA framework is primarily addressing.

With this grounding in mind, mechanics “describes the particular components of the game, at the level of data representation and algorithms.” It’s the conclusion of the paper that “all desired user experience must bottom out, somewhere, in code.”

Dynamics “describes the run-time behavior of the mechanics acting on player inputs and each others’ outputs over time.” A layer that is greatly affected by the sum of both mechanics and aesthetics. “Seemingly inconsequential decisions about data, representation, algorithms, tools, vocabulary and methodology will trickle upward, shaping the final gameplay.”

Aesthetics “describes the desirable emotional responses evoked in the player, when she interacts with the game system.” The sum total of everything, in a way, but also how we choose to represent it.

These three components can be considered “separate, but casually linked,” and should be used as lenses through which you can look at your game design. An important aspect of this is that players will generally see the aesthetics first, while developers often obsess over the mechanics. This difference in view is important, and the framework urges you to bridge it by switching your game design perspective to one focused more on aesthetics.

One way to do this is by employing Marc LeBlanc’s “8 kinds of fun,” sometimes referred to as LeBlanc’s Taxonomy. A setup that looks at what combination of eight key emotions you are trying to emphasise.

Critical Vocabulary for Games

Greg Costikyan, another veteran game designer, suggested in 2002 that “[t]o understand games, to talk about them intelligently, and to design better ones, we need to understand what a game is, and to break ‘gameplay’ down into identifiable chunks. We need […] a critical vocabulary for games.”

This piece hits off with “if it isn’t interactive, it’s a puzzle, not a game,” based on Chris Crawford’s musings in his early book on game design, The Art of Computer Game Design, from 1980. So interaction is what separates a game from a puzzle. But interaction in itself isn’t good enough. There also needs to be decision making; “interaction with a purpose.”

To make decisions relevant, you need goals. Ways to succeed or fail and choices to make along the way. But those goals cannot be trivial to achieve, or you may get bored instead. To make the goals non-trivial, we need struggle.

“We want games to challenge us,” writes Costikyan. “We want to work at them. They aren’t any fun if they’re too simple, too easy, if we zip through them and get to the endscreen without being challenged. […] That isn’t to say that we want them too tough, either. We feel frusrated if, despite our best efforts, we wind up being slogged again and again.”

The last concept Costikyan identifies is endogenous meaning. To describe what it is, he uses Monopoly money as an example. “Suppose you’re walking down the street, and someone gives you $100 in Monopoly money. This means nothing to you; Monopoly money has no meaning in the real world. […] Yet when you’re playing Monopoly, Monopoly money has value; Monopoly is played until all players are bankrupt but one, who is the winner. […] Monopoly money has meaning endogenous to the game of Monopoly.”

To summarise Costikyan’s essay, a game is “[a]n interactive structure of endogenous meaning that requires players to struggle toward a goal.” The game designer’s job is then to complete that whole.

Why We Play Games

Next up is Nicole Lazzaro’s excellent Why We Play Games: Four Keys to More Emotion in Player Experiences. Lazzaro further elaborates on the MDA Framework’s type of thinking, particularly in what the framework refers to as Aesthetics.

“Games are structured activities that create enjoyable experiences,” starts the paper. “They are easy-to-start mechanisms for fun. People play games not so much for the game itself as for the experience that game creates: an exciting adrenaline rush, a vicarious adventure, a mental challenge; and the structure games provide for time, such as a moment of solitude or the company of friends.”

To write Lazzaro’s paper, her game design consultancy XEODesign “went off in search of emotion and found Four Keys to releasing emotions during play.” Each such key is “a mechanism for emotion in a different aspect of the Player Experience.”

The first key is The Player: The Internal Experience Key. “Generate Emotion with Perception, Thought, Behavior, and Other People.” In the text, it’s also called “games as therapy.” A player that plays because of this key is playing to clear their mind, feel better, avoid boredom, or being better. “Games with this Key stimulate the player’s senses and smarts with compelling interaction.”

The second key is Hard Fun: The Challenge and Strategy Key. “Emotions from Meaningful Challenges, Strategies, and Puzzles.” It achieves this through emotions such as Frustration and Fiero (“an Italian word for personal triumph”). “Games with this Key offer compelling challenges with a choice of strategies.”

The third key is Easy Fun: The Immersion Key. “Grab Attention with Ambiguity, Incompleteness, and Detail.” Also referred to as “sheer enjoyment of experiencing the game,” dipping into senses of wonder, awe, mystery, and so on. “Games with this Key entice the player to linger, not necessarily in a 3D world but to become immersed in the experience.”

The fourth and final key is Other Players: The Social Experience Key. “Create Opportunities for Player Competition, Cooperation, Performance, and Spectacle.” Crucially, both inside and outside the game itself — community can meet the emotional goals of this key just as much as in-game features. Teamwork and camaraderie. Rivalry and competition. Schadenfreude and amusement. “Multiplayer games are the best at using this Key, although many games support some social interactions through chat and online boards.”

The paper provides a more clear description of each key, but what’s incredibly useful with these keys overall is that many games can benefit from supplementing a focus on one of them with additions of another. For example, if your game is highly competitive (“Other Players”, “Hard Fun”), it can still be nice to have a change of pace organising inventory or fiddling with other menu bits between sessions (“Easy Fun”).

The Art of Game Design

Jesse Schell’s The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses is one of the most commonly mentioned books on game design. If there was any such thing as a standard volume on game design, this would probably be it. It’s an excellent book and has two major elements that makes it useful (in my opinion).

First of all, the chapters themselves frame many key elements of game design. First comes the chapter The Designer Creates an Experience, which clearly emphasizes that the game “enables the experience, but it is not the experience.” This is an important thing to understand if you want to grasph Schell’s perspective on game design.

From there, the book goes both broad and deep. The Venue where you play the game plays a role. The Game itself, the Elements, Theme, and Idea it’s composed of. That it’s improved through Iteration and made for a Player and made to create an experience in the Player’s Mind based on the Player’s Motivation. To achieve this, there are Mechanics that must be in Balance. There can be Puzzles, Interface, Interest Curves, you can tell a Story, allow Indirect Control, and build a World.

As you can tell, it’s a very complete view. This also doesn’t list the many more practical pieces of advice that the book goes into, such as how to make a Profit, the value of Technology and Playtesting, and what Documents you may need to write and how.

The second thing the book provides is just over a hundred “lenses.” Each lens is something you can look through when you analyse your game. They’re available in a deck of cards that you can get fairly cheaply and that has great utility whenever you need inspiration in your game design work. An example lens is the Lens of Balance, which tells you to ask the questions “Does my game feel right? Why or why not?”

A Game Design Vocabulary

The struggle to find a good game design language is the subject of Anna Anthropy and Naomi Clark’s book A Game Design Vocabulary as well. It takes a more high level approach than Schell’s book, perhaps most similar to Greg Costikyan’s article mentioned earlier.

“You’d think 50 years would give game creators a solid foundation to draw from,” writes Anna Anthropy in the introduction to the first chapter. “You’d think in 50 years there’d be a significant body of writing on not just games, but the craft of design. You’d think so, but you’d be disappointed. […] I see evidence that what both creators and critics desperately need is a basic vocabulary of game design.”

First are Verbs and Objects, and the relationship between them. Such relationships determine the Rules of the game you are making. Verbs are actions. Objects are things that can perform or be affected by actions. Perhaps a Hero, controlled by the player, can Shoot and an Enemy can Die. Suddenly, you have also added choices. If there are two enemies on your screen and you must pick which one to shoot.

Given that the game is made up of Rules divided into Verbs and Objects, then Scenes are the “units of gameplay experience that unfold during and create the pacing of a game as it’s played.” Many tabletop role-playing enthusiasts swear by scenes in this way, where scenes have beginnings, things at stake, and ends. Both like and unlike directing a movie. More specifically in Anthropy’s vocabulary, “[t]he purpose of scenes is to introduce or develop rules, to give a chance for the game’s cast — its verbs and objects — to shine, and a chance for the player to understand something new about them.”

Finally, Context “is what helps a player to internalize those otherwise-abstract rules that make up our game.” Spiky things are dangerous, red barrels explode, and nazis are (in fact) the baddies. Context affects many things, and is where much of a game’s content comes in. But it’s also what determines how we compose the scenes for our game.

However. This is only half of the book. The second half, written by Naomi Clark, looks at a game as a conversation between the game and the player. It dives more into the difference between authored and emergent stories, and how games can both be a vehicle for the former and provide unique room for the latter.

Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design

Another way to look at and talk about games is by breaking them down into their mechanical components. In the book Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design, Geoffrey Engelstein and Isaac Shalev have compiled a selection of tabletop game mechanics in encyclopedic form.

This book starts from Game Structure, calling out games that are cooperative, competitive, team-based, solo, and more. It goes from there into Turn Order and Structure, talking about claim turns, roles, random turn order and many more. Then Actions (meaning player actions), in some of its many forms. Resolution, for handling outcomes when the outcomes are contested. Game End and Victory collects some favorites (and criticised but common ones, like Player Elimination). Uncertainty then deals with topics like short-term memory limits and push-your-luck mechanics.

In its broader sections, the book then compiles details on Economics, Auctions, Worker Placement, Movement, Area Control, Set Collection, and general Card Mechanics.

Many tabletop designers swear by these terms. They may say they’re designing a “worker placement set collection game,” for example. Most of the time, these mechanics are known quantities and designers can talk about them in terms of how well they fit with a game’s themes or other mechanics. It’s also a handy way to make experiments. For example, “worker placement with a common pool of workers” makes sense as a mechanical idea, and gives you something to build on top of.

These are not quite definitions per se but descriptions of game elements that are common enough to be generalised.

Find Your Own Words

You should read and explore the craft of game design as much as you can. But you shouldn’t strive to define it in general terms. As you can see in the previous examples, even when there is overlap, there is never any real consensus. Games and game design are nebulous things and we all find different things important.

Once you design your own games you should make up your own terms too. Don’t put effort into complying with definitions you didn’t make and don’t discuss what definitions mean or which definition is right. All of that time will be wasted compared to the time you put into figuring out what your game is about.

Make up your own words that can inform how you want to design games. But by all means, do so by taking inspiration from the wealth that is out there, and use the work of great designers to inform your own designs.

Game Design is the Knowledge and Skill to create a Commercially Viable Game that Satisfies their Audience by providing enough “Value” to them through that Genre’s “Appeals” and providing sufficient Content or Challenge that translates to a certain amount of playtime.

If Game Development is the Skill that make you be able to complete and releases a fully functioning game.

Game Design is the Skill that makes the Players care about your Game enough to want to Play It and Buy It.

That is the definition of Game Design that is the most “inclusive” based on a summary on what the actual fuck is going on and what you should do and learn.

There is a also a Stricter definition of Game Design based on stricter definition of what a “Game” actually is, or Orthogame, and is relation to the actual Gameplay and the Objective Definition of “Fun”.

Games are Structured Play that Tests and Challenges the Learning and Mastery of the Player Skill and Knowledge of that Game.

Fun and Play is Voluntary Learning that is a fundamental part of Brain’s Play Mechanism.

The only Subjective thing about it is only their Preference in the kind of Player Skills they want to engage in at the time, to Learn and be Challenged by.

“Genres” are an already Successful Formulas that has been found that have a high amount of Depth for that Learning and Mastery of particular Player Skills.

Everything else has nothing to do with Gameplay, they are completely diffrent Values from diffrent Appeals. For things like Story and Narrative the Value is like reading a book, it has nothing to do with the Gameplay.

Even Interactivity and Agency does not necessarily have anything to do with Gameplay, the Value of something like Role Play is in the Creative Player Expression and the Improv Acting by Interacting and getting Feedback from an Audience. There is a reason you see Youtube Let’s Play that Role Play certain Characters, the engagement with an Audience is the point and why it works.

With Creative Expression to who do you express yourself to?

What is called the “many types of fun” are in fact completely diffrent Systems of Value and Appeals and have nothing to do with the True Objective Definition of Fun, Play is fundamental animal behavior. Rats can Play Games, but the cannot Read a Book, so how are they having “Fun” reading a book?

Did you read the post? There’s no consensus and has never really been a consensus on any of these definitions. You can pick your own for your own work, however, and that’s the point I’m trying to make. Discussing the definitions is less fruitful.

Your Brain is the Consensus.

It’s based on your Biology not Ideology.