Something that has been missing from this blog is how players will experience playing your systemic games. What the inputs and outputs represent and what kind of game they help make. So that’s what this post is about.

Also, please, if I’m wrong about something or you want to book a talk or just chat about systemic design, don’t hesitate to e-mail me at annander@gmail.com.

Inputs, Outputs, and Feedback

A system is defined by inputs and outputs. What will be discussed in this post is what these inputs and outputs can be. There’s also a third layer, player feedback, that will be kept for a future post.

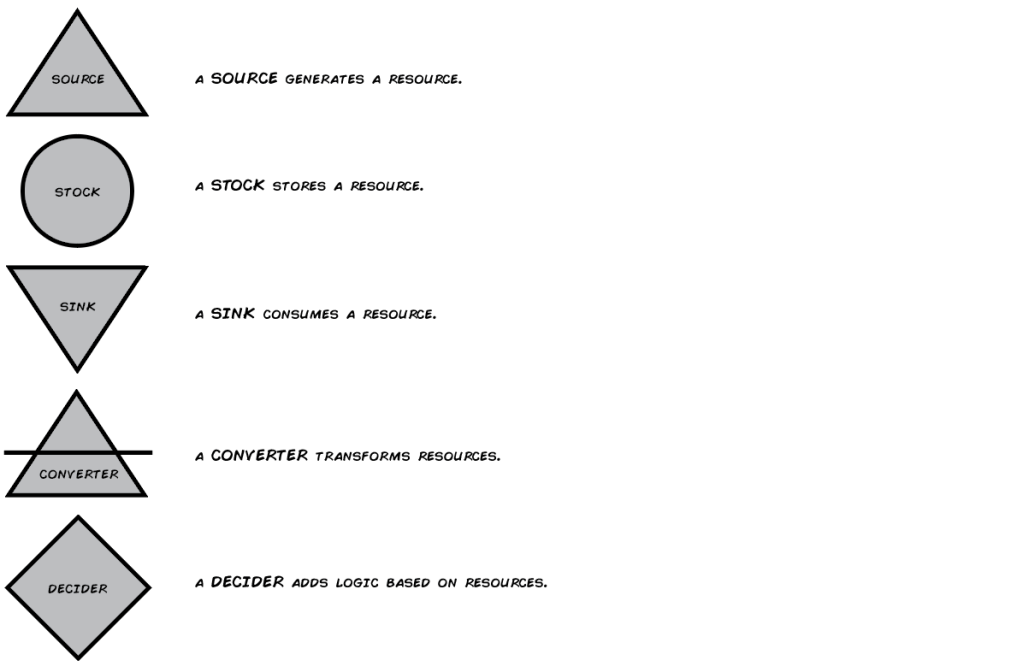

The five nodes illustrated below can be used to represent most systems. If you want a more in-depth explanation, I highly recommend that you get the book Advanced Game Design A Systems Approach, by Michael Sellers, or that you play around with Machinations.io.

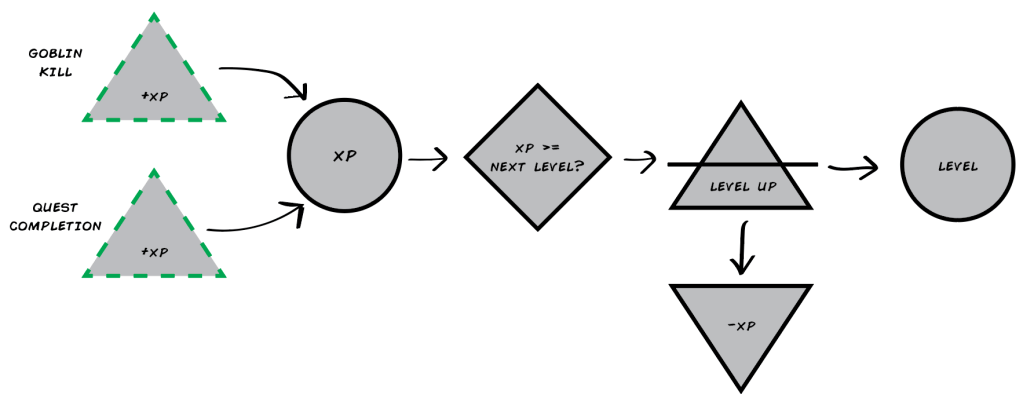

These five nodes are used in all of the examples in this post to illustrate how different types of inputs and outputs can be represented. The focus is on what the player is contributing to the system. Nodes where the player is involved use a dashed green outline instead of a solid black outline.

Accumulation

Many game systems are built around the concept of accumulation. You collect things or points and you push towards higher and higher tiers of something. This has been discussed before as the subject of gamification. But accumulation is more than just the slow rise of a progress bar. Where it gets interesting is what you decide to award points for and how fast.

Read the linked article if you want more on this subject, however. It’s a good illustration of a simple system, but it’s not terribly hard to design.

Modular Functions

Modular approaches are likely the most common way to implement systemics, from Sim City in the late 1980s onwards to Factorio in the 2010s. Whether you think of the state, component, or decorator patterns, there are many good programmatic ways to separate logic into modules, and to then allow the modules to do their thing individually while contributing to a more complex behavior. In fact, this blog has covered modular systemic guns in the past (it remains one of the most viewed posts).

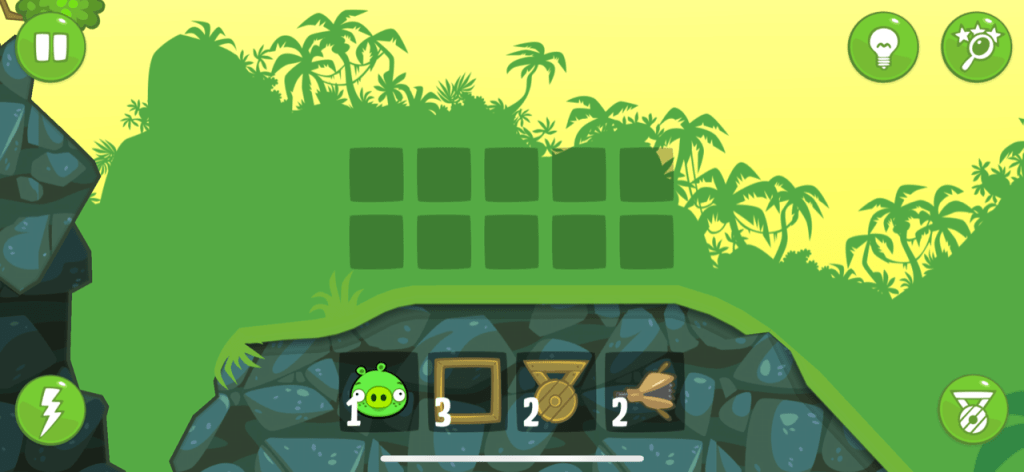

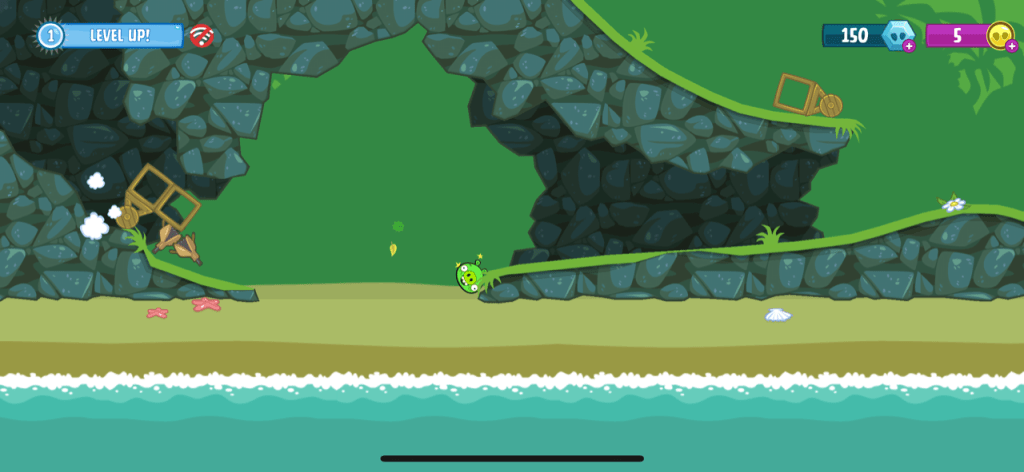

In Bad Piggies, for example, you are given a grid where you can freely place the vehicle parts you have access to. In the early game, these are simple. Boxes to build the frame, wheels that will roll against solid ground, and things like the bellows in the screenshot below, that will give you a slight push if you tap it during play.

The goal of the game is to get the little green piggie to the goal flag. You’re free to set the components any way you want, as long as you include the little piggie, and the game provides this as a sort of puzzle for you to solve.

Many levels will also have bonus stars or different styles of pickups or environment dangers (like explosives) that will affect the behavior of your vehicle.

What’s interesting is that the behavior of each individual part is very specific. A wheel will roll. A frame will hold things together. Bellows provide a small amount of force in the opposite direction of the nozzle when you tap it. As a developer, this is a big strength, because you can work out how each part functions in isolation and then let the parts interact to produce the vehicle.

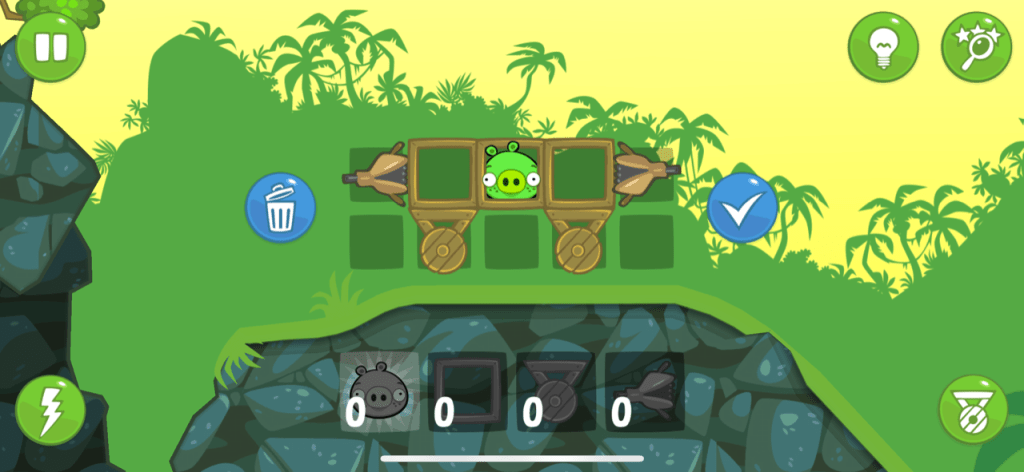

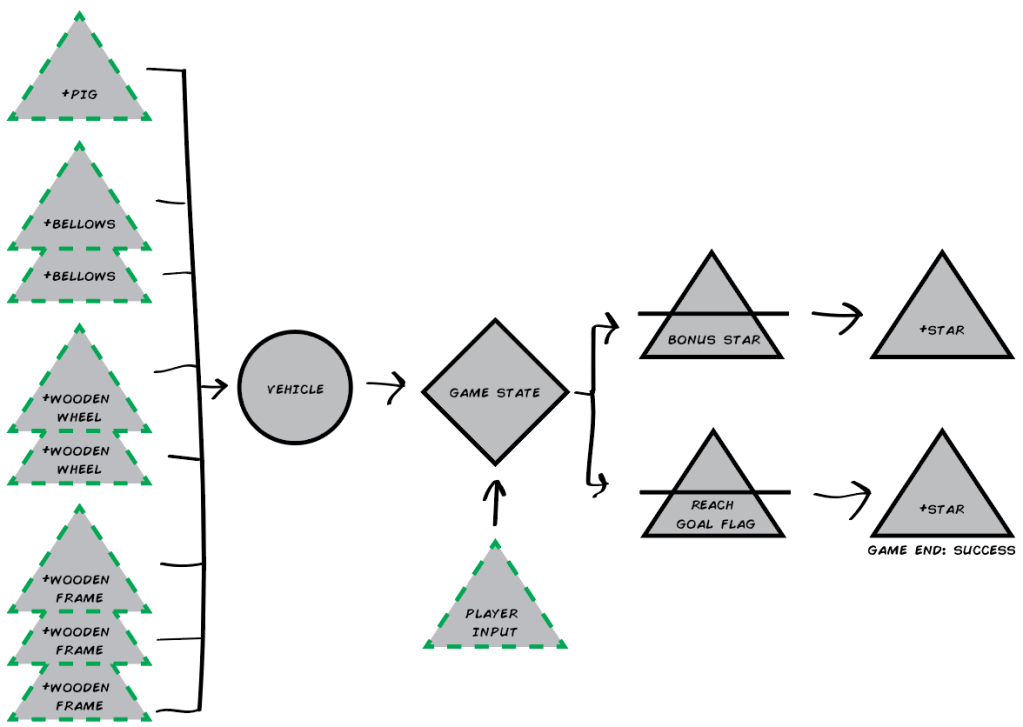

We get something like the following as the systemic representation of Bad Piggies. The player is responsible mostly for putting the different vehicle parts together, but also provides some measure of realtime input for parts like the bellows.

We could go into more detail of course, and look at each part as a separate system. The bellows has a position within the vehicle and it has a nozzle direction where it will apply its force, for example. It takes player input and generates force output. This is certainly an exercise that may be more useful if you are documenting a full game, for your own benefit, but let’s keep it at this high level in this post.

In the later game, there are springs, fans, engines, propellers, explosives, and many other vehicle parts that each provide a specific effect. The strength of this type of approach is that you can design each module separately and the design becomes incredibly scalable as a result. You can go with just the minimum parts needed to make vehicles, or you can invent hundreds of different parts with dynamic effects, all using the same setup but making new types of vehicles possible.

Roles

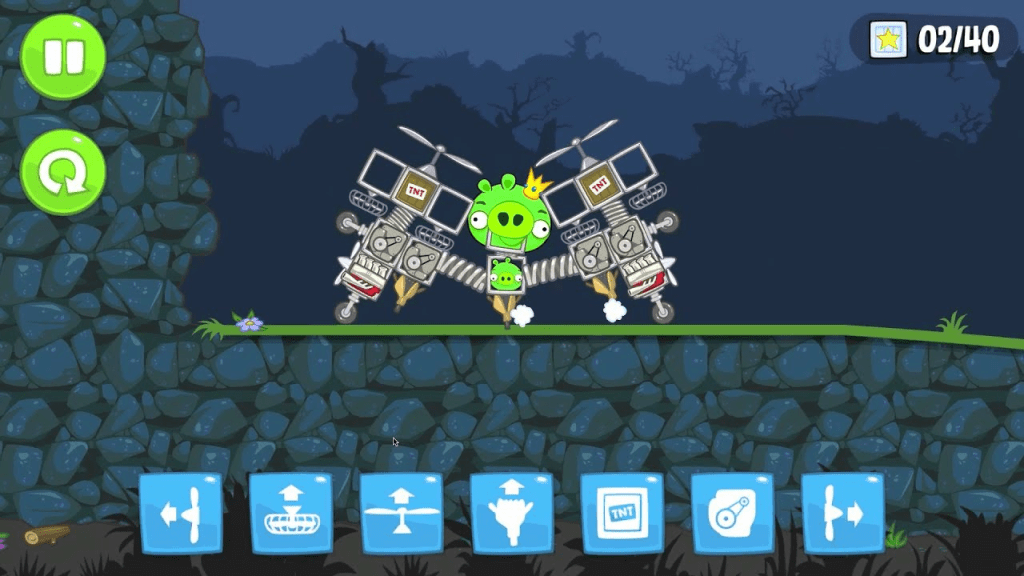

Something related to the modular approach is to give roles to whole objects. This is what Lemmings does with its skills. In Lemmings, the goal is to get as many of your titular lemmings to the level’s exit as you can. The more you get to the exit, the higher your score.

Unfortunately, the average lemming is only walking mindlessly forward and won’t make any decisions on its own. You must instead assign skills to lemmings that change their behavior in order for you to redirect the tide of suicidal rodents towards the exit.

For this purpose, at the bottom of the screen you see a number of different skills that the lemmings can be given. This is the primary resource you have available. In the first level, there’s really just one of them, and that’s the Digger. The game will later expand to include a whole range of skills that must be used in combination if you want to successfully lead your lemmings through the increasingly tricky levels.

Once a lemming is given a skill it will keep repeating it with the same singular focus as the other lemmings. If the skill has a completion state, such as falling through the finished downward tunnel of the Digger, it will revert back to its skilless form and you need to spend another Digger resource if you need to.

The levels in Lemmings become increasingly hard and you must be careful about how you use the resources you have. The fewer the better, and the more lemmings you can bring to the end without having them fall into an abyss, burn, get crushed, etc., the better!

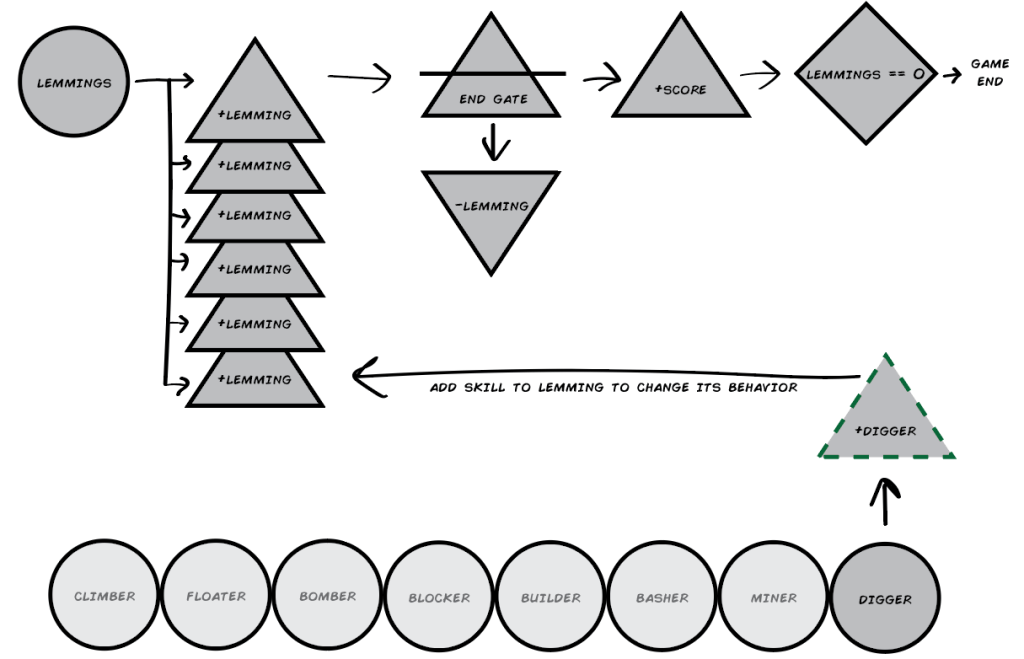

Illustrated as a system (below) you will see that there’s not that much the player is taking part in. Rather, the player is assigning skills (“roles”) based on the movement of the lemmings as a group and the context of the level played.

Item Interaction

A popular intent-based dynamic is how resource collection items are handled in many survival games. If your goal is to build a house, for example, you may have to go through a chain of items that represent different stages in an upgrade process before you can finally build the wall you wanted. In many ways, it’s functionally the same as accumulation (above), but it’s representing each stage with items and equipment instead of points and progress bars. Each stage is usually connected to diminishing returns, as well, where you may first need just a few resources and will then gradually need more and more.

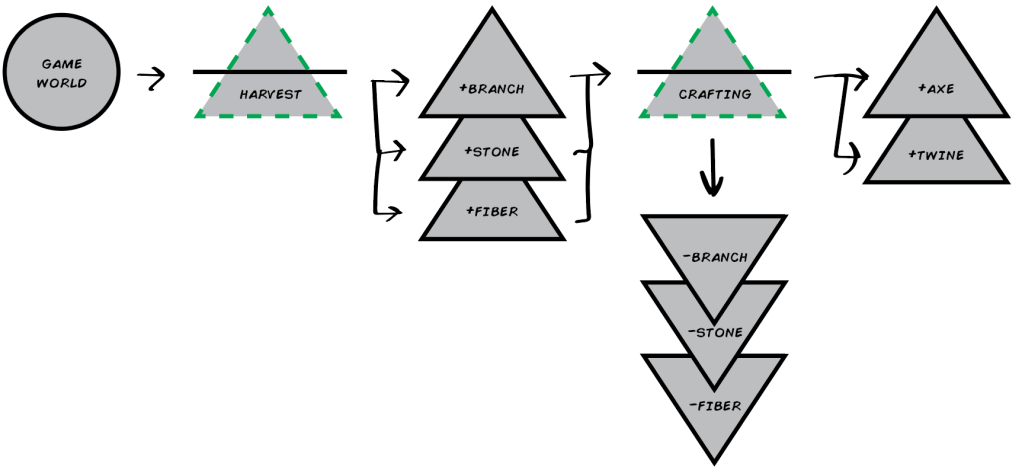

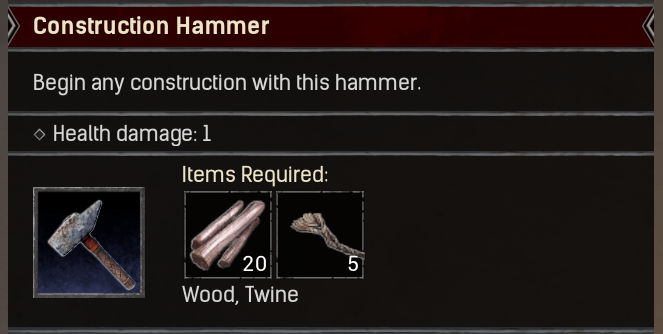

In Conan Exiles, for example, you need a Construction Hammer to be able to build the pieces of your house. It requires accumulation of XP before you can build this hammer, but let’s put that to the side for a moment. Accumulation is a comparatively simple system. Instead, let’s look at the crafting.

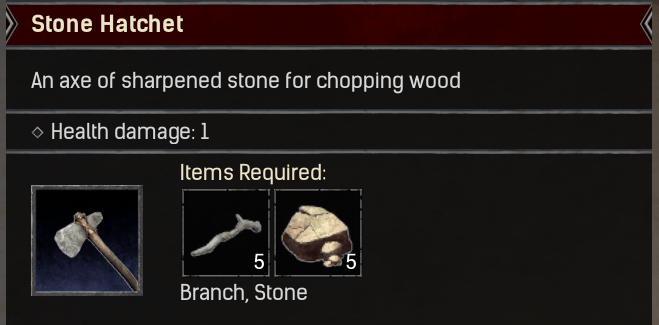

To get Wood, you need to first have a Stone Hatchet. Crafting this requires Stone and Branches, both of which you can find lying on the ground:

Once you have the required resources, you can then craft the hatchet through the game’s crafting menu:

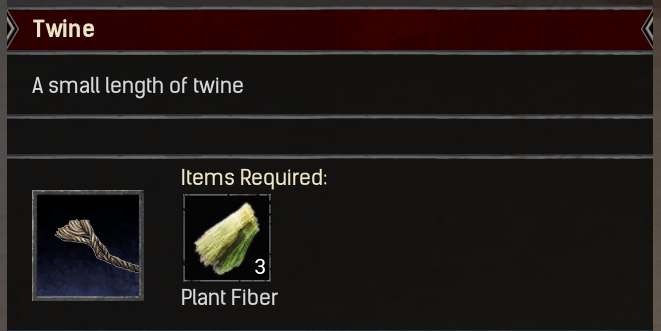

You also need Twine to make the Construction Hammer, and Twine must also be crafted. In this case, you need only one resource: Plant Fiber. You can collect this from bushes that can be found in the game world. Once you have enough (3), you can craft Twine as well.

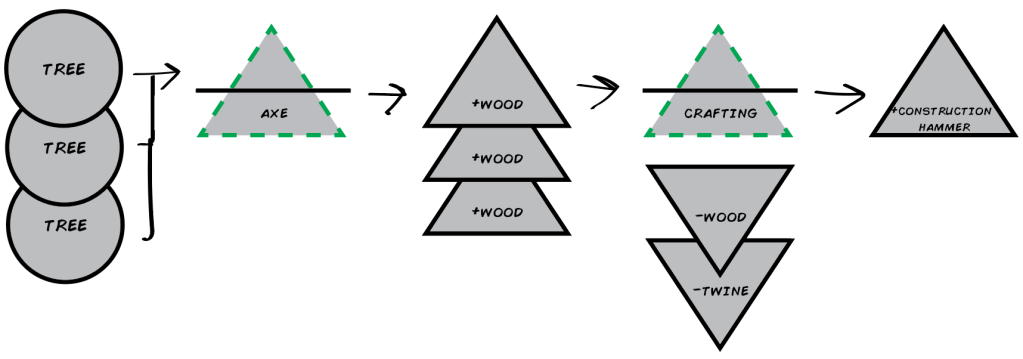

If we simplify this into a system and highlight the parts where the player interacts with the system, we get something like the following diagram. Note that the consistent thing with all systems we’re looking at is that the Sinks make sure that you always lose more than you gain. This is often what we talk about when we talk about “engagement mechanics” in game design: things that keep the player occupied.

Once you have the axe, you can partake in the next step of the system, which is the collection of Wood. You can find this by chopping down trees, and once you have enough Wood (20) combined with enough Twine (5), you are ready to craft your Construction Hammer.

Of course, there are progress bars at each crafting stage as well, and what you will immediately realize once you want to build your house is that you’ll need quite a lot of stone to build the parts. It’s like the classic hill climber illustration, where you crest the first hill only to find a taller hill behind it. This means that Time is realistically the most restricted of all the resources you are working with, and it’s incidentally a resource we sometimes forget to take into account as game designers because while we develop our games it’s not as transparent as the others.

Player Interaction

Something that the Ultima games explored in the early 90s was the use of in-world objects as representations of actions. Below is a series of images from Ultima VII: The Black Gate, where the Avatar (the game’s protagonist) is going through the process of baking bread.

This isn’t a realistic representation of the process of baking bread, by a longshot, but it’s close enough that it feels realistic. You need to go through the motions one by one and you need access to the right equipment and resources.

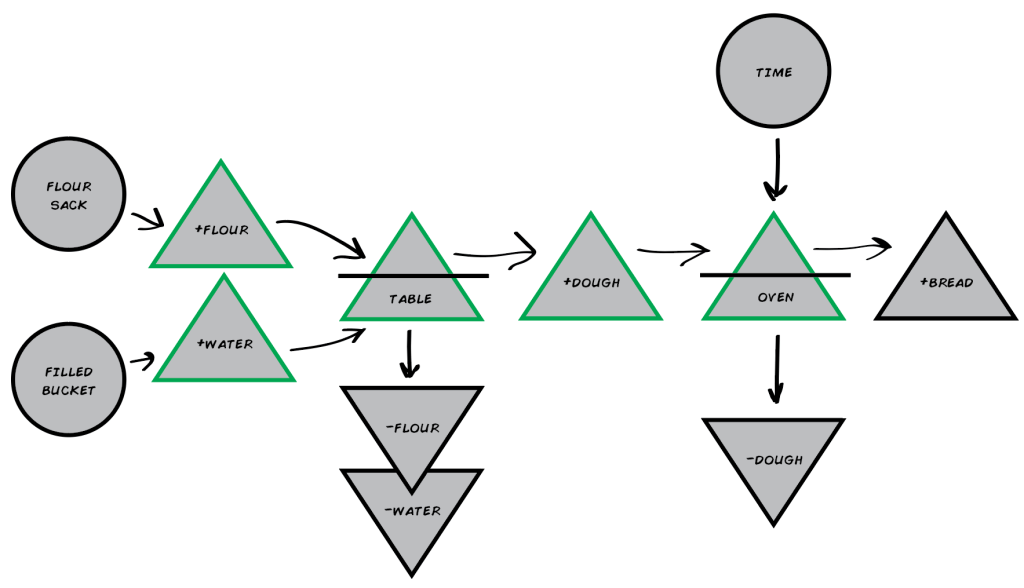

In systemic terms, its stocks are containers in the game world, its sources are ingredients gained from those stocks, and its converters are interactive objects also represented in the game world. This same way of representing systems through direct interaction is quite common in Roblox experiences today. Good game design lives on!

Some games will also have failure states, such as a risk that you burn the bread if you don’t take it out of the oven quickly enough and you get a “charred bread” item instead of the loaf you really wanted. The key thing is that the systemic transitions are player actions. You need to interact directly with the flour sack to put flour on the table. This time around, Time also comes from its own functionally infinite Stock. This is an important input for many games, because it’s one of those numbers you have a decent amount of control over as a designer. Increasing or decreasing how much time is needed to reach certain thresholds is a very important lever.

If we boil the baking of bread down into nodes, we get something like this:

Build Min-Maxing

Some games are played as much via spreadsheet functions as within the game itself. The system interaction in such a game is often called “min-maxing” because you’re minimizing the bad and maximizing the good with the intent of providing the best possible outcome from a given set of numbers. Causing highest possible amount of damage, for example.

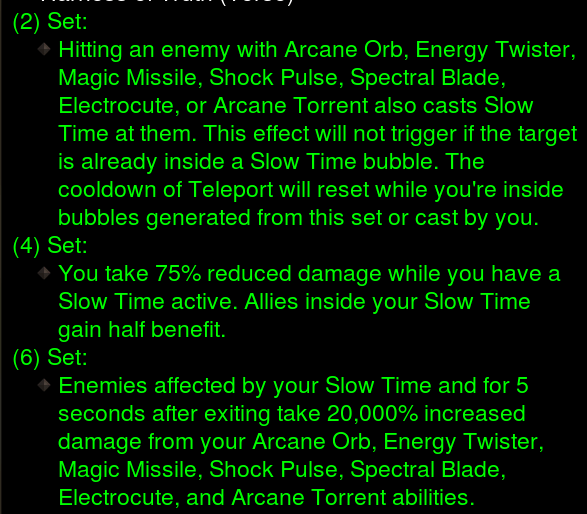

The example here will be from Diablo III. One key element to how you plan a build in this game is the item sets. Each set provides a specific bonus dependent on how many of the set items you manage to equip.

Below is the full set bonus provided by the Wizard set called “Delsere’s Magnum Opus:”

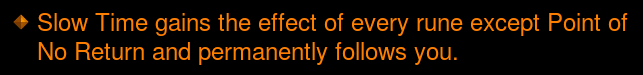

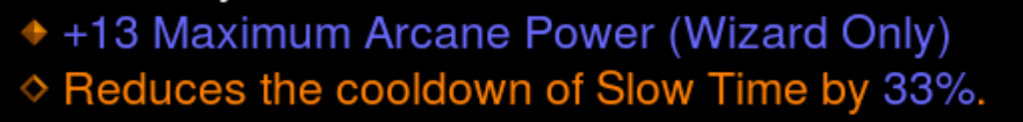

There’s a lot happening here, but we can quickly tell that Slow Time is an important feature. This is one of the defensive spells you have access to as a wizard. So with this build, some extra items can also be equipped to synergize with this spell:

Crown of the Primus makes it so that Slow Time gains all of the different rune effects that can be customized, with one exception, and also that there’s a constant Slow Time effect centered on your character. Gesture of Orpheus makes it so you can have more Slow Time bubbles active at the same time, by decreasing the cooldown of the effect itself.

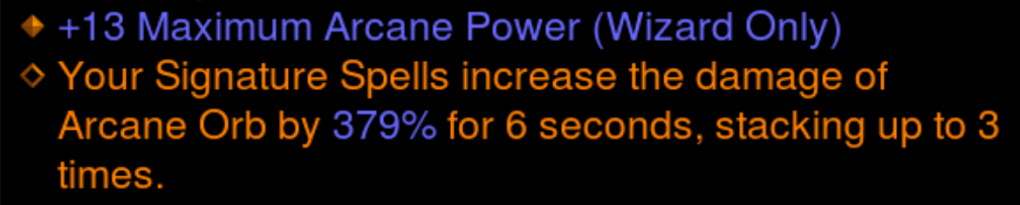

The next one is a bit different, but ties into the last power of the item set. It’s an off-hand item held by the wizard and increases damage of the Arcane Orb spell quite considerably:

There are more items in the complete build as well, but you can see the theme by now: equip a set and then try to figure out which other items that enhance the set’s features.

As always when it comes down to numbers, the results can be somewhat hilarious. Mind you that this build was also limited to what was available at the time the screenshots were taken. There are builds that are far more optimized than this example. There are also nuances lost here. For one thing, all of the blue text in the screenshots vary between “drops” of the same item, motivating you to keep playing to get better versions of the items in your build. (In other words, Time rears its head once more.)

You can set things up to deal a lot of damage by combining the right items. But there are also some interesting effects on how you play. Teleport synergizes well with the set items, since it can be used much faster between Slow Time bubbles. This implies that you should be flitting back and forth between bubbles and dealing damage to enemies caught inside them or near them.

As a player, your role is to combine the right items at the build stage, and then play to maximize their return. You interact with the system by selecting items in the inventory and by playing the game correctly based on the items you selected.

Conclusions

The reason I wrote this post was the realization that the player’s part in a system isn’t always obvious. It turned out to be a useful experiment, and I am now trying to use these simplified graphs as reference points for other projects.

They’re not exhaustive analyses, by far, but hopefully they can provide some food for thought.

(Interesting post|Nice post|That was a fun read}

Great insights on the importance of understanding player experiences in systemic games! Your breakdown of inputs, outputs, and feedback is both informative and thought-provoking. Keep up the good work!

Thanks

Chris Cantrell