Note: this post has been revisited and expanded a few times, going from four scales to six to provide a more holistic set of scales.

A big part of what makes systemic design work is your own design mindset. The relationship you imagine between yourself as the designer and the player who will be playing your game. I’ve talked about this before, in the third of the immersive simulation posts, and thought it’d be good to expand on it a little bit.

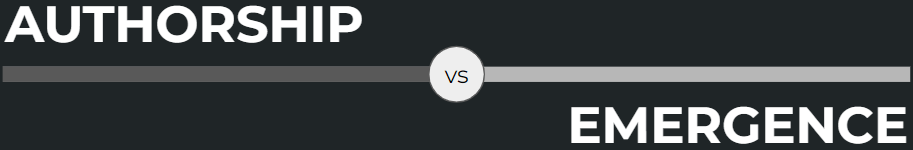

Imagine a scale between authorship and emergence. As an author-designer, you have a specific thing in mind, and anything that risks deviating from this picture in your head must be removed or restricted. As an emergence designer, you look at your game as objects, states, and rules—the things I keep rambling about in this blog—and it’s up to the players to discover what the tools you’ve made for them can accomplish.

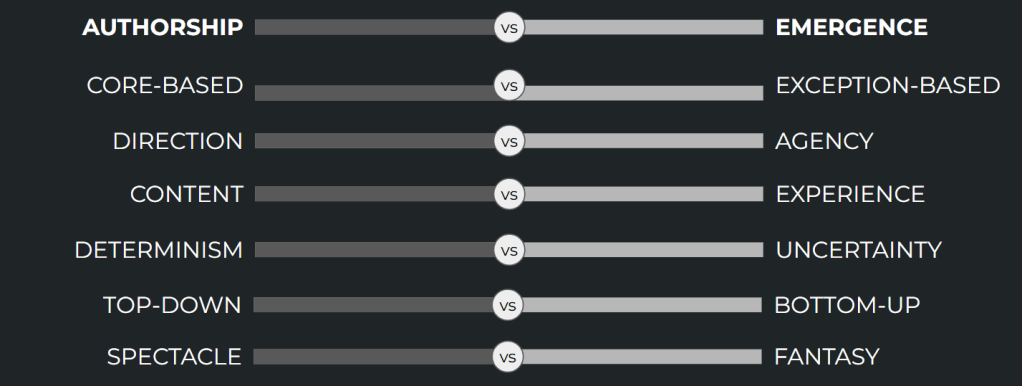

This is simple enough to wrap your head around, but it’s also not very helpful. Few games fit squarely into one or the other. Instead, we can look at it as six scales and a master scale. These are what I will present in this post.

As always, if you disagree, have opinions, or want to contact me for other reasons, you can do so by commenting or via annander@gmail.com.

Core-based vs Exception-based

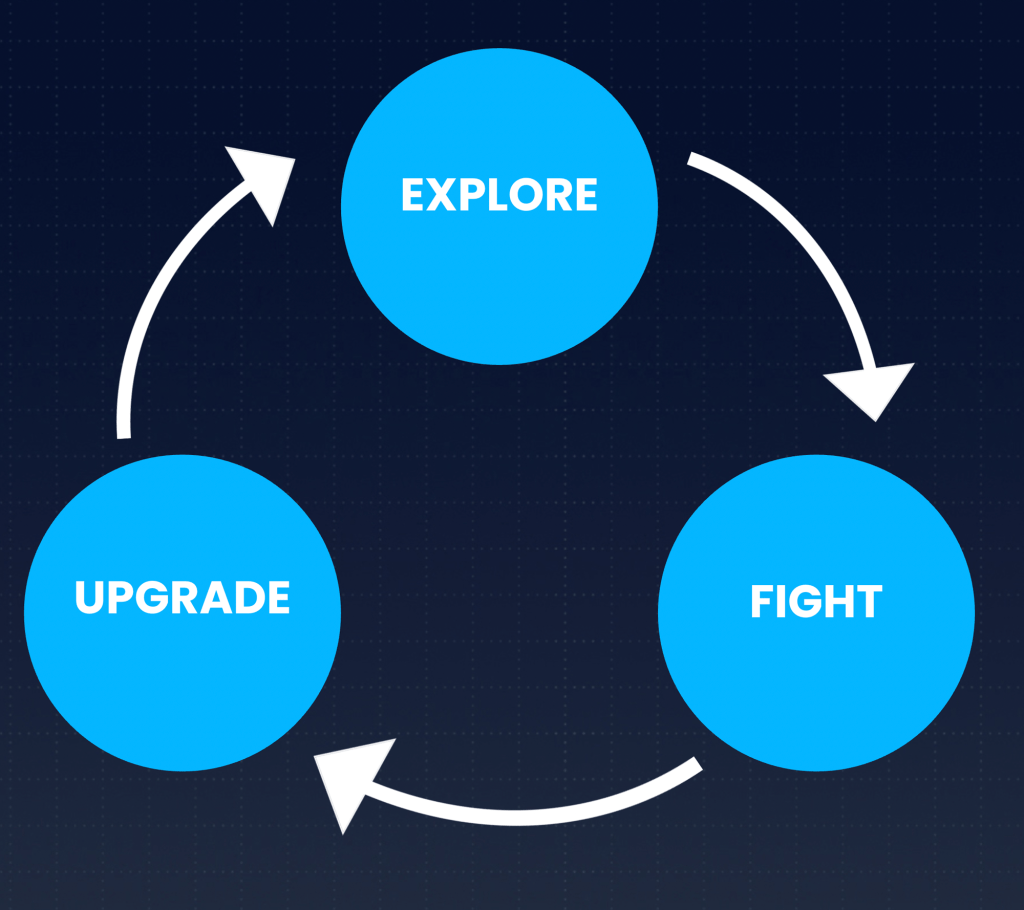

Many argue whether game design should start from theme or from mechanics. But you can argue just as much about the prevalence of a core loop versus an exception-based design.

Core-based

There’s something cynical about the boiling down of game design into a “core loop.” But it’s also incredibly useful. It may have been the misrepresentation of a quote by Halo 2 designer Jaime Griesemer that led to the prevalence of the “core loop” in modern game design.

“In Halo 1,” he said in the Halo 2 behind the scenes video, “there was maybe 30 seconds of fun that happened over and over and over and over again. And so, if you can get 30 seconds of fun, you can pretty much stretch that out to be an entire game.”

What he really meant was more nuanced than this. “[T]he worst part is, everyone uses it to mean exactly the opposite of what I meant when I said it! […] There was a whole second half of the quote […] where I talked about taking that 30 seconds of fun and playing it in different environments, with different weapons, different vehicles, against different enemies, against different combinations of enemies, sometimes against enemies that are fighting each other.”

This longer quote is a perfect distillation of a core-based game. You have a strong functional core—usually made with features rather than systems—and you repeat this core in different contexts throughout your game. It’s carefully paced, impeccably directed, and focused on its strengths.

Exception-based

Most exception-based designs still rely on a core of sorts, but it tends to be much smaller and more consistent. The key elements that form the game come from exceptions to the core.

Good examples of exception-based designs are Metroidvania games, where each ability adds a unique new touch to the gameplay; card games, where each card provides an exception in its own right; and survival games, where the things you can craft and the objects you can collect generate a panoply of interacting exceptions.

In the words of Magic: The Gathering design veteran Mark Rosewater, “What we’re trying to do is give our players a whole bunch of tools that they then can explore and do things with. It’s not our job to find the solutions. It’s our job to make the tools that they get to find them with.” Designers make the exceptions—players find out what they’re for.

Exception-based games may break down because the players find dominant strategies or ways to abuse certain exceptions. But if you are a true believer, this lack of guardrails can actually be the perfect expression of emergence. As with the developers of Slay the Spire, who allow players to use the most powerful combinations of rules exceptions when they come up so they can have fun while breaking the game. It happens rarely enough that it’s a fun exception to the game’s overall style of play.

Direction vs Agency

Whether you lean more towards a predefined core feature set or a more systemic set of exceptions, another thing you need to consider is direction versus agency.

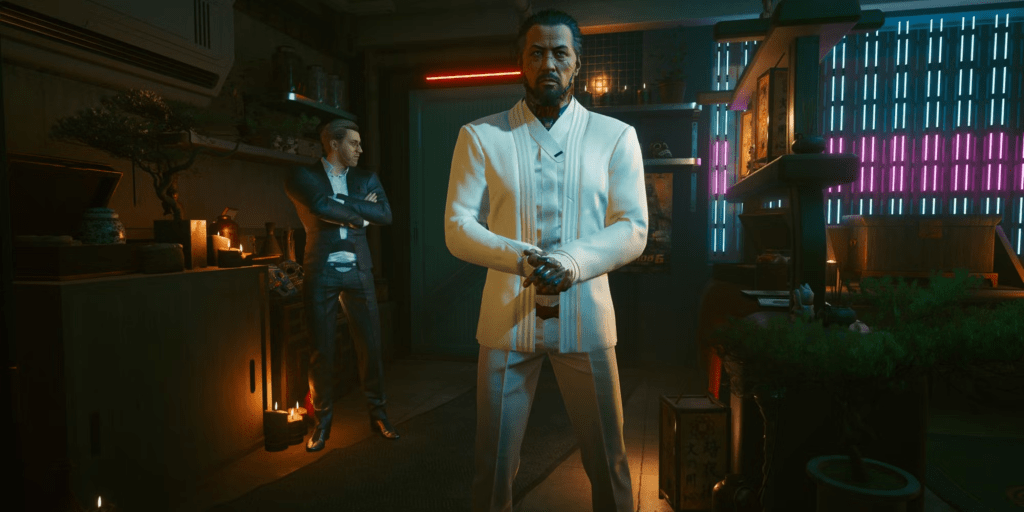

Direction

A game that is closely directed will always play out the same. It may provide the illusion of choice, or even ask the player to make active tradeoffs, but all of it is an illusion. Smoke and mirrors. You are not going to save the character that dies a tragic death, nor are you going to defeat the enemy that will come back in a bossfight later.

Direction can provide players with impressive awe-inspiring moments—it’s the strength that direction gains from its cinematic heritage. Maybe said best by someone with a movie background, such as Josef Fares talking about A Way Out: “A scene that is only playable for you for about 60 seconds. I’d say over 300 animations, only playable for you for 60 seconds, and it’s never coming back.” Scripts, storyboards, and motion capture animations: all products of direction.

Though those 300 animations are certainly unique, the gameplay of interacting with them in A Way Out is rarely more interactive than pressing forward on the left stick. The spectacle is amazing, and the direction is what makes it valuable, but the player has very limited agency.

Agency

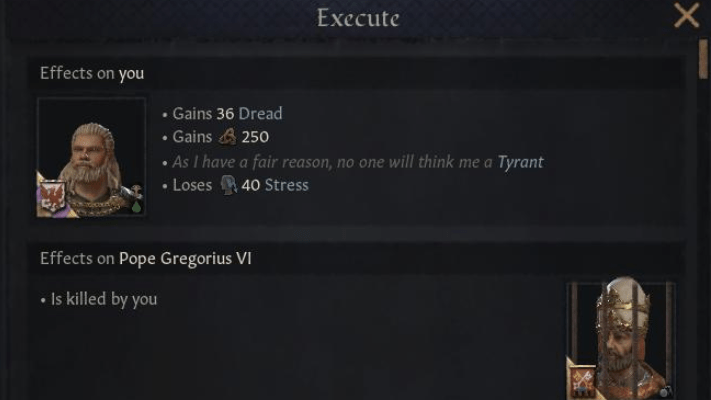

Speaking about player agency is tricky. Some players will take it to mean that everything they attempt should be rewarded, and if it’s not, the game doesn’t give them enough agency. Let’s use a slightly less stringent definition and consider agency a factor of the game respecting player intent.

If a game with high agency gives you a gun and shows you that you can kill characters with this gun, then this is a permission that the game needs to respect. If the player later decides to shoot the game world’s chosen one in the face, this should be perfectly fine. The chosen one should die. It follows the rules of the game, and it follows player intent. If your game applies rules this consistently, it also provides a high degree of player agency.

Quite obviously, agency is the opposite of direction. The moment a plainly killable chosen one cannot be killed because the game designer decides that it’s so, they have exercised authorship and have directed the outcome against player agency.

Content vs Experience

I have complained in the past about our industry’s (and our fans’) use of the word “content,” and will probably keep complaining until we start making games in smarter ways. But content has its place, and when it comes to authorship it’s many times easier to plan content than to build experiences.

Content

“We do level design. We do art. We do new mission packs. We do new power ups that are basically variations on old power ups,” said Daniel Cook in his talk on creating new genres. “[E]ssentially we’re a content industry and we sell content.”

One more asset. One more level. One more character model or weapon prop. We know how this works, so we can plan it and we can take our script and list all the things required to realise it. Whether we build 15 or 1,500 is a matter of budget and staffing. There is very little unpredictability for the development process itself. (Unless we change things mid-production, of course, but that’s a separate discussion.)

Many times, this is exactly what players want. A feature-rich game with a compelling narrative and plenty of optional side missions to engage with. If you buy the latest AAAA single-player blockbuster, it’s often what you expect and hope to put your next 100 hours into. Then you want the DLC, the expansion, and the sequel, to provide you with even more content.

Experience

Then-CEO of Starbreeze, Mikael Nermark (R.I.P.), said in an interview in 2012 that, “We don’t talk about games, we don’t talk about genres, we just talk about building the best experience, whatever that means for that particular project.”

I have personal opinions on whether this was true at the time, which I will save for another day, but the sentiment of Nermark’s statement is compelling. An experience can be something where you are an active participant. Something where your personal input matters, where elements like immersion and role-play can happen. It can come from games like DayZ, where the experience grows out of dynamic player-player interactions.

Rather than burning through content, you’re taking the same content and doing more things with it. Sometimes because of your own vivid imagination as a player, and sometimes because you wanted to try to play the game a different way. It’s what you do when you set the sliders differently in a new session of Civilization, or replay Dishonored with high chaos. The same content, but a new experience.

Determinism vs Uncertainty

Many words in game development have different meanings to different developers. They may even have individual meaning. One such word is “randomness.” We often use randomness to be a negative thing, because something happened that we didn’t want to happen. But it can be equally important for what makes a game interesting.

Determinism

The most deterministic a game will ever get (in this context) is when it shows you an unskippable cutscene. Every player will see the same cutscene, paced the same, focused the same. The moment you allow even a modicum of interaction, the player can go against your intentions. Controlling the camera, for example, may make the player miss a crucial on-screen event because they were looking the wrong way.

This is probably why games with strong authorship often rely on cutscenes to convey their narrative elements, and maybe also why Hideo Kojima allegedly said, “The human body is supposed to be 70 percent water. I consider myself 70 percent film.”

Other ways to achieve determinism is limitations of different kinds. Having to open a specific door to progress, walk through a certain hallway in a specific direction, and so on. Level design can assure that players see certain sights and scenes in a predetermined order.

Uncertainty

“Games are uncertain and must be so to remain interesting,” concludes Greg Costikyan in his book Uncertainty in Games. “[B]ut sources of uncertainty are manifold.” In this book, many different sources of uncertainty are explored, from simple randomization to player interaction. Will I roll the 6 I need? Is my poker opponent bluffing when they go all-in?

Whenever you can’t fully know the outcome of an event, there is uncertainty at play, and it’s one of the key ingredients for emergence. Uncertainty can come from the physics system that yields crazy results in Goat Simulator; or the dynamics of orc politics in Shadow of Mordor.

This end of the scale is for you if you embrace this uncertainty. It’s not the one thing that makes a game interesting (which is part of Costikyan’s conclusions), but considering which forms of uncertainty you want to include is a fruitful design space.

Top-down vs Bottom-up

When you have ideas for your game and start implementing it, a common way to begin is to translate the high level concept directly into objects. You will have characters, so of course there’s going to be a Character base class. Some engines will provide these expected classes out of the box. Let’s look at this top-down approach, and also its opposite, the bottom-up approach.

Top-down

A high level concept or “core fantasy” is the narrative or conceptual layer that can be used to inform your whole design. But it can also be used to inform your fans—not just you as the developer. Days Gone game director Jeff Ross said in an interview; “My design philosophy is you’ve got to stick with your core fantasy. So whatever core fantasy your IP is trying to create, if players are buying into it, they want it delivered upon.”

This focus at the high level means that you will construct a game top-down. This core fantasy will be used to make decisions and anything that may go against it will be either downplayed or removed. If a player can go off the beaten path implied by the core fantasy, they won’t be able to stray far. Deacon St. John—the protagonist of Days Gone—can’t be made to stop sulking or searching for his lost wife, for example. Those are fundamental parts of the high level concept and character writing.

Bottom-up

In his book, Creation: Life and How to Make It, Steve Grand discusses how to construct emergent behavior, stating “[t]he mistake is to start with the outward behaviour you want to see, and work back towards some equation that produces it, rather than start with the fundamental physical processes that are at work, and from them build outwards to generate the behaviour.”

The solutions used in Steve Grand’s life sim game, Creatures, is to emulate how real life works using sensory input, neurones, and actions, as well as the inputs of the player to punish or reward the creatures as they go about trying to understand their world. There’s no principal high level concept to start from, beyond an idea of emulating life. No model for the detailed behaviour. Instead, the behaviour is a consequence of the parts.

Jeff Orkin’s classic Goal-Oriented Action Planning becomes a similar type of model, where actions and state describe possibilities, and the plan that comes out of the planner is the actual behaviour. The opposite of something like a behavior tree that strictly defines the whens and hows.

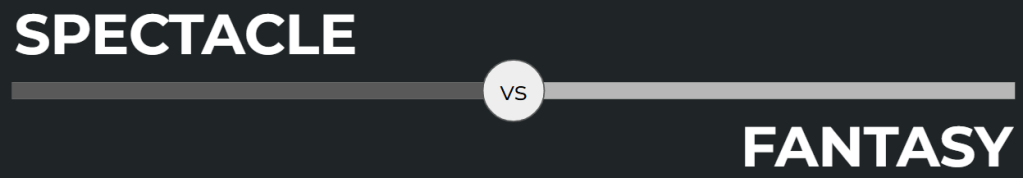

Spectacle vs Fantasy

In self-determination theory, you talk about extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. An extrinsic motivation comes from without in the form of rewards or other stimuli, while an intrinsic motivation is something that comes from within yourself. If we want, we can look at the next scale’s two extremes as a similar thing. Spectacle is an extrinsic thrill; fantasy is an intrinsic thrill.

Spectacle

A spectacle is an occurrence regarded in terms of its visual impact. Something striking, awe-inspiring, and compelling. When the nuclear bomb goes off in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, or when you realise the outcome of each of the different interactive set pieces in What Remains of Edith Finch. Fireworks displays are spectacles. Absurd bossfights are spectacles.

In video games, spectacles are expensive to make and tend to require either explanation or staging. Spectacle therefore dovetails nicely with direction and determinism, since it’s hard to guarantee that the player will experience the spectacle as intended if this is not assured somehow.

Fantasy

Immersion is incredibly powerful. To visit another world and become another character. Conjure up an image of a virtual persona that becomes so real that you may even shed its tears and feel its anger.

Games are “fantasy first” when they present a strong fictional grounding for their premise. When they ask the player to play out a role, such as a liber-tea delivering helldiver in Helldivers 2, or a thief in Thief: The Dark Project. The first is an example of the game presenting a fiction and asking you to immerse yourself in it; the second is better described in the words of Paul Neurath, one of the founders of Looking Glass.

“We want a more singular experience that’s focused on a role,” he said. “We know what thieves do. Players know what thieves do. It creates an immediate context, which is especially important if you’re doing an innovative game.” The player fantasy as a means to inform the player of what to expect.

Authorship vs Emergence

After these six segues, we’re ready to look at the master scale again. The scale that goes between Neil Druckmann and Warren Spector; between Authorship and Emergence.

Authorship

Anyone who has ever had an amazing thing appear to their mind’s eye and desperately wanted to convey it through art has desired to author something. To convey specific emotions to another person. We may choose writing, painting, or game development, as our avenue of communication, but the artistic urge is still the same: to make people feel something.

“My thing I always go back to,” said Cory Barlog. “[I]s that sense of finishing ‘Castlevania: Symphony of the Night,’ and that castle flipping over, and just going, ‘Oh my God, that was amazing! I have so much more to play!’ It was astounding. I think I’ve always been chasing that. I think my entire career, I have been like, ‘I want that kind of epiphany.'”

Flipping the castle for the player, giving the player a pivotal moment that gives something value. Supposedly it’s what drove the narrative twists in the 2018 rendition of God of War that Barlog was the director for.

This is authorship. Having a strong vision where the stars align to bring something to the player playing your game, and making sure that this strong vision comes through to everyone that plays the same game.

Emergence

In his memoir, Sid Meier tells the reader about his storied game development career. The concept of interactivity and the focus on the player’s experience of playing your game is consistent throughout. One comment he makes in describing game design is that “[l]ike chess, each piece’s function was easily understood, and only after you began looking at moves in combination did the really interesting paths emerge.”

This approach is the complete opposite of having a deterministic pre-defined turn of events in mind. You’re now building the pieces that will form the whole and then handing them over to the players. This leaves plenty of room for emergence to happen, and often it will be things you never even intended that provides the most value.

Sid Meier’s approach isn’t better than Cory Barlog’s, it’s just based on different priorities, and you need to know where you want to take your own projects. Emergence happens when you let go of authorial control.

The Scales

Put it all together and you get six scales where you can put your design intentions, and a seventh scale to serve as their umbrella. We can look at the left side as authored and the right side as emergent.

Systemic games invariably benefit from a right-leaning design space, but as you will probably realize, very few games even among immersive sims and other highly systemic games are leaning completely into one side or the other.

Thief: The Dark Project has plenty of direction in its narrative and plenty of content in its level design and storytelling. The same goes for The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, and most definitely for Baldur’s Gate III.

By adding more exceptions, more agency, more focus on experience, more uncertainty, and designing it all in a bottom-up manner, you will be pushing your game towards the emergent end of the spectrum. Just make sure to be honest both about what you want to achieve and what fits your game best.

What I hope you can take with you from this post isn’t that you should skew everything towards the right, even if I’d certainly play your game if you did. It’s that you need to be aware of your intentions and consciously choose where on these scales you place your own game design. Once you’ve done that, you need to stick to it.

5 thoughts on “The Systemic Master Scale”