This post is a continuation on a previous combat design post.

Shooting, stabbing, strangling nazis; or just quick-meleeing with knives to humiliate PvP opponents that didn’t see us coming. Melee combat is a big deal in video games and has been since forever.

This post will try to break down how you turn a traditionally feature-rich game design like melee combat into an object-rich one instead.

But before we do that, let’s look at standard representations of melee combat in video games.

Types of Melee Gameplay

I will start by going through a number of gameplay types that you see repeatedly for melee combat, and I will give them strange names that you may or may not agree with. This is for the sake of argument. You don’t need to agree on how I classify any of this. It’s also not a reflection of which games are good or bad—only how they solve common problems and which verbs they focus on for the player.

Note that, for preferential reasons, I’m mostly talking about 3D animation. There are many 2D games, from Hollow Knight to Nidhogg and beyond that do incredibly interesting things with melee combat, but I’m not talking about them here.

Feature-Rich Melee

You have the heavy attack and the quick attack. You can parry. You can also riposte if you time the parry right. You have throwing knives, shuriken, caltrops, wire traps, and javelins; each with a special role in the combat simulation. A feature-rich combat system is something like Ryse: Son of Rome, the 2018 God of War and its sequel, or Ghost of Tsushima. Production values are often through the roof, the story is in focus, and most of the game’s challenges rely on cycles of retries until you succeed the way the script demands.

These types of games are very expensive to produce and even more expensive to fill with content. They are also the complete opposite of what will be discussed in this post, since they are entirely content-driven and do not rely on any simulation or systems. Since they can’t be described using rules, they must often rely on visual or aural cues and will often focus on repetition and timing because of this. Look for the hint, and time your button press based on it.

Player Activities

- Unlocking new tools.

- Learning which tool works when.

- Looking or listening for gameplay signals.

- Retrying until successful.

- Finishing the story.

- Waiting for animations to complete.

Content-Based Melee

The next common type of combat is mostly about timing, but it’s also about learning the nuances of the game’s content. Games like Street Fighter do things this way, but so do the Soulsborne titles. Each character or weapon has a defined set of animations and behaviors, and you need to learn things like which strike comes after each other strike, how far each strike’s reach is, which frames reduce damage during a dodge, and so on. There’s no way for you to know these things when going into the game: they must be learned.

Good games of this type are tuned to perfection, providing a high degree of satisfaction when you start mastering the techniques involved. But they are also strictly tied to their content patterns, whether this is an AI whose wide axe swing is always telegraphed by an overhead swing, or the longsword the player finds which’s quick attack is a swing and heavy attack is a thrust.

If we assume that Raph Koster’s theory of fun holds true, which is that fun comes from learning, this style of melee combat is extremely successful at providing it. In fact, I’d argue it’s one of the best styles for this type of fun and likely has a great deal to do with their success.

Player Activities

- Learning the controls.

- Learning the content (timing, reach, etc.).

- Anticipating your opponent.

- Finding new learning opportunities.

- Exploring what has been learned.

- Mastering what has been learned.

- Overcoming patterned challenges.

- Retrying failed challenges.

Freeflow Melee

Allegedly, the first tentative steps towards what would become the oft-plagiarized “freeflow” style of combat was in the Catwoman video game released in 2004. But it really hit off with Batman: Arkham Asylum (AA) in 2009.

You have three actions in AA: attack, stun, and counter. Though this plays as a mix of feature-rich and content-based, it’s not about critical timing or even following prompts, but about getting into a certain “flow.” The protagonist is directed in roughly the right direction to take out the strategically right enemy in the moment. If you fail to execute it right, you are taken out of this flow state.

One common criticism against this style of combat is that it’s just button-mashing or at least feels like it. It can also be criticised for being too easy. This is of course completely valid opinions, but challenge is not the goal. It can certainly be part of it, and later iterations on a similar formula—like Spider-Man and Shadow of Mordor—add enough features to dip more into Feature-Rich Melee than Freeflow. But for the original freeflow games, the goal is to make you feel like Batman. You see a group of thugs and you think, “I can knock those out.”

Freeflow is a great type of combat system to let you build character confidence.

Player Activities

- Lining up attacks.

- Maintaining flow.

- Neutralising critical threats (with correct timing).

- Building character confidence (narrative connection).

- Planning, while waiting for animations to complete.

GUI-Based Melee

The next type of combat is probably more contentious to define. At its most extreme end, you have the knife fight in Resident Evil 4 that is a cutscene with quicktime events added. At the other end, you have games with specific context-sensitive interactions that represent more complex actions that the player has no interaction with. For example, a special combo that can be triggered under certain circumstances.

Player Activities

- Anticipating the UI.

- Reacting within the correct window of opportunity, or failing.

- Retrying failed sequences.

- Learning the cues through repetition.

- Waiting for animations to complete.

Semi-Freeform Melee

I will refer to this as “semi-freeform,” because though you have more direct control than in purely content-based melee combat games, you must still spend some time learning the game’s animation content.

The two most prominent examples of games that solve melee this way are Chivalry and Mount & Blade. The first uses animation content to direct an attack based on how you are aiming, but lets you retain control throughout the attack; the second has you provide directional input before the attack and places your weapon in a warmup position before you release to deliver the blow. In both games, you are free to aim to guide the weapon.

What these games do really well is model the differences between various weapons. In Chivalry, you can use a chained weapon to get behind someone’s shield. You can use a lance to deal tremendous damage if you time it right as you ride your horse, in Mount & Blade.

Player Activities

- Aiming where to hit.

- Moving to position yourself better.

- Guiding the direction of attack.

- Judging distance to make the most of each attack.

Body-Control Melee

Some games have tried to give us control over the physical extremities or positioning of our protagonists. It’s an uncommon way to do combat and probably for good reasons. Most of the time when you played Die by the Sword using its mouse-based “VSIM” controls, you ended up repeating a horisontal swing over and over while moving towards your enemy. More like a lawnmower than a fighter.

But there’s certainly something compelling about the idea of controlling your avatar’s virtual arms. The Fight Night boxing games have a very distinct control setup using flicks of the analogue sticks.

The probably coolest thing about this type of interface is that it slightly resembles the process of learning to fight in the real world, even if it’s just a digital representation. Picking up the sword not knowing what to do, and gradually mastering the horisontal flailing, just like a real warrior.

Player Activities

- Learning the interface.

- Practicing the interface.

- Applying your knowledge of the interface.

Peripheral Melee

With VR, we’ve had games like Blade & Sorcery that does freeform melee using VR controls. But even before then, we had the Wii console, and titles like the yanky Red Steel and The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess. But the Wii games that did melee combat mostly boiled down to wiggling or waggling the controller and didn’t amount to the incredible immersive duels that many probably hoped for when the Wii was released.

The issue that no peripheral-based melee game has quite managed to solve (yet) is how to handle the physical properties of your weapon in case of things like parries, and how to handle judging distances and enemy proximity. The disconnect between simulation and peripheral is still too great.

Some of these games are still a ton of fun, however. There’s a quiet promise in the idea of a peripheral-based melee combat game.

Player Activities

- Learning the physical controls.

- Learning the content.

- Learning the concessions between controls and content.

- Judging distance.

Freeform Melee

What can be considered “freeform” in this context is when you have direct action control. Your actions as a player are to slice and dice; not to trigger animations doing it for you. This gets very tricky with characters and animations, since there’s no room for them to play their animations without knowing something about the game’s context beforehand, but it can be extremely satisfying as gameplay.

When we see these types of melee combat in games, it’s usually in a more abstract form that doesn’t portray characters at all and doesn’t need animation. From Fruit Ninja to melee-themed rail shooters.

Player Activities

- Perform actions analoguous to in-game actions.

- Apply intent to the game simulation.

Finishing Moves

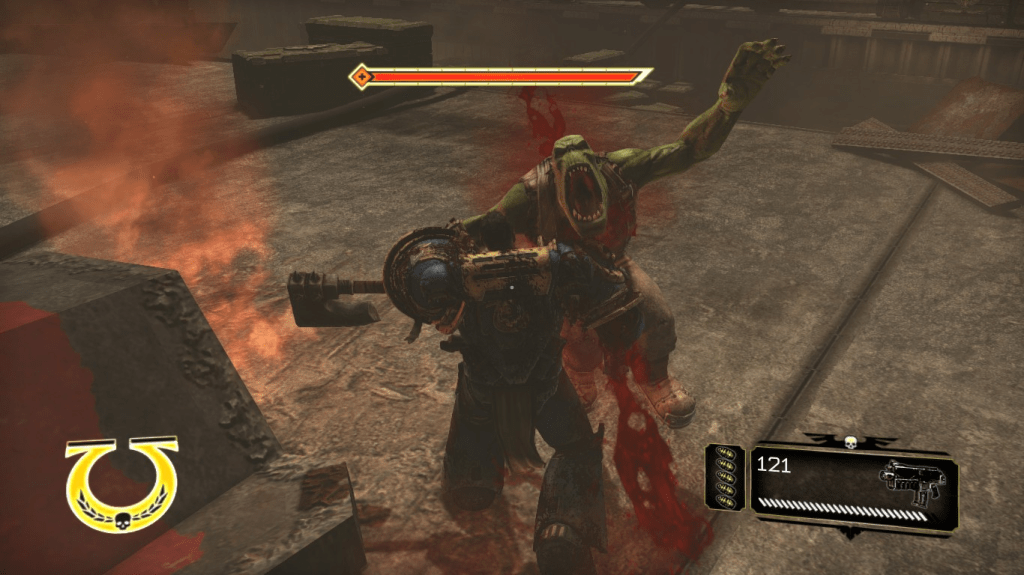

Maybe most iconically from Mortal Kombat, a finishing move is a way to mark beyond a shadow of a doubt that an enemy is defeated and to create a potentially gratifying moment of feedback to the player. Some games use this entirely for flavor, while others make finishing moves an integrated part of the game’s balancing. Consider Doom (2016) and its glory kills, that provide you with a health boost.

Player Activities

- Learning context-sensitive cues (usually as icons in UI or flashing textures in world space).

- Timing context-sensitive cues.

- Managing resource requirements (e.g., Doom‘s chainsaw gasoline, Space Marine‘s health).

- Waiting for animations to complete.

Quick Melee Attack

Primarily in first-person shooters, you have a tendency to move towards your opponents or them towards you. The distance closes as you fire your weapons, you get close enough to stare at each other viciously, and then the first of you who realises that there’s a quick melee-button will win the day.

A variation on the quick melee attack is what you find in games like Vermintide, where there’s a push attack that lets you gain some distance from enemies without dealing much damage.

One common way to animate these attacks is to start from the impact frame and then animate back to the idle pose. Either directly or with one or two tweening frames to smooth the strike transition. The reason for this is that it feels very close to the direct action shooting you are engaged in most of the time in a FPS.

Player Activities

- Learning to time the attack right.

- Learning the balance of how much damage the attack deals and when to use it.

- Triggering the attack at the right time.

- Waiting for animations to complete.

Immediate-Mode Melee

As the complete opposite of content-based melee, let’s call this style of melee “immediate-mode,” from the UI method of directly updating graphical elements when data changes. The principle here is the same: to immediately provide player feedback by executing the triggered melee attack. Games that need to feel responsive and fast often utilise this type of mode.

Picture how the Barbarian in Diablo III starts an attack by snapping straight to the peak of the animation’s telegraphing pose and then executing the strike extremely fast; often faster than you can see. It’s responding the moment of the click rather than by using the click as a trigger.

By not having to learn animation content, you free up your mental bandwidth to focus on the battlefield instead.

Player Activities

- Assessing threats.

- Killing enemies.

- Timing critical (often statistical) abilities represented as targeted or area attacks.

- Waiting for cooldowns to finish.

“Realistic” Melee

For some reason, realism tends to mean that things slow down and become animation-driven. It seemingly comes more from swordplay motion capture and attempts at detailed physics simulation than from any investigations into what makes a swordfight a swordfight.

It’s certainly the most confusing mix of combat as sport and as war. On the war hand, many such games allow you to come up with unorthodox plans. But on the sport hand, it’s still a points chase, with experience and kill counts and objectives to complete.

It’s hard to really know how to evaluate these types of games. The quotation marks are in the headline because they tend to be very selectively realistic. There’s no Arma 3-equivalent simulation for melee games. At least not yet.

Player Activities

- Learning the length and reach of animations.

- Learning the rules for different arms and armor.

- Waiting for animations to complete.

Takedown Melee

A close relative of finishing moves is the takedown. Where a takedown in martial arts tends to mean a method to take your opponent to the ground, its use in game design is usually as a way to disable an opponent. It can be to choke them unconscious or to stab them to death with a sharp object.

Player Activities

- Learning which takedown options are available.

- Planning when to use a takedown.

- Waiting for animations to complete.

Melee as a Tool

Sometimes the melee combat is not the main attraction but merely one of several tools in a complex toolbox. This is the type of melee employed by games like Thief: The Dark Project and Dishonored. But it’s also similar to what you get in survival games. Say, Rust.

In such a game, the utility of the melee weapon is clearly defined and you can learn its rules and then make use of the tool when you find it necessary. In some games, it’s a backup. In other games, you’re a highly competent killer but you can decide not to be.

Player Activities

- Learning the tool’s rules.

- Learning how the tool complements the game’s other tools.

- Deciding when to use the tool.

- Waiting for animations to complete.

Ragdoll Melee

Video game physics can be employed in many different ways but is actually very rarely used to model melee combat. It can be used as an additive effect that detect if your blade hits a wall and that causes you to stagger or lose your balance if this happens, or it can be used to turn slain foes into ragdolls. But it’s surprisingly rarely used for the combat itself.

There are of course exceptions, with comically dynamic games like Gang Beasts and more aspirational titles like Exanima being two of them, but game physics are generally too unreliable to provide the kinds of balanced experiences we usually want from our games.

Player Activities

- Learning the game’s actions.

- Learning the rules of the game’s simulation.

- Waiting for the simulation to generate results.

Systemic Melee Combat

One thing covers melee combat in video games like a wet blanket: character animation. You are often trying to learn the specific timing of an animation, waiting for an animation to complete, or both. Not always, but often enough that the rest of this already long post will discuss animation.

If we want to make any kind of melee combat with characters fighting, we need to start from character representation and animation. How it works, how it’s used, and how we can break it down into modular systems.

Skeletal Animation

We’ll have to make concessions in the names of stability, playability, performance, and many other things affected by how animation systems work under the hood. Which concessions we make will have a profound impact on how our combat is played. It may even restrict or reaffirm the design choices we make.

Firstly, content is expensive to make. This is just as true for animations. Animator is a full-time job, or rather a whole department with many full-time jobs.

Secondly, there is a great risk that we get stuck with technology we can’t use for our intended purposes, particularly if we choose a game engine with solutions that don’t fit with our goals.

Skinned Mesh

First of all, you have your mesh. The 3D object that the game engine will be pushing out to the GPU. This is just like any other mesh, with vertices, edges, triangles, UV mapping, vertex colors, and so on. But it incorporates some extra data in the form of skin weights. More on those soon.

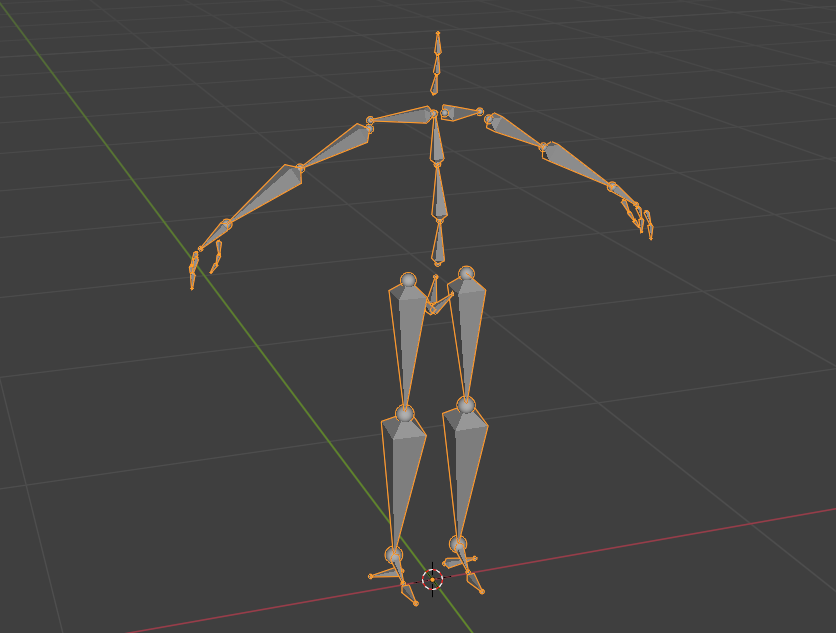

Skeleton

Just as with real people, an animation system has a skeleton under the skin. This skeleton is what will actually be animating. What’s neat about skeletons is also that meshes that share the same skeleton can all use the same animations.

Skin Weights

Skin weight settings can usually be painted onto a mesh and is expressed as a range between 0 and 1 that is used to determine how much a vertex is affected by the transformation of a specific bone. Zero means not at all, while one means it follows the bone exactly. Traditionally, zero is blue and one is red.

Keyframe

When the skin weights have been painted in, you can start manipulating the skeleton to be able to pose the mesh. You can then store this as keyframes and export it from your tool of choice either along with the mesh or as separate animation assets, depending on your game engine.

Blending

Once you have two or more keyframes, you can blend them together into animations over time. Under the hood, this can use any kind of interpolation. Linear, curves, easing, or some combination.

Types of Blending

Once you have the frames, you can do lots of fun stuff with them. Blending them can be done using manually assigned curves, programmatic easing functions, or any of a wide range of other methods.

Interpolation Combat: Bumping

This is actually the point where we can introduce our first type of melee combat! Bumping happens when an animated attack enters an enemy space, usually a grid space or hex. It can either result in the occupant being removed (“killed”) and the attacker taking over the space, that the attacker is removed, or that the attacker bounces back because of a successful defense.

In-Place Animation

When we build an animation loop and play it in our game engine with little regard to how the animation behaves inside the game, this can be called in-place animation or animating in place. The mesh and animation are simply loaded and rendered and left to do what they do best. Gameplay may control when a certain animation is triggered, and we may also want to use state machines or other graph tools to blend based on gameplay data. Maybe go from crouching to standing, or from walking to running.

Animated Combat: Fire-and-Forget Animation

This is the second type of combat that is extremely common. Just play the swing or thrust animation you’ve made and let it play out no matter what. Just parent a weapon to the character’s main hand and use the frame information to turn the weapon “on” for impact calculations. It can be just a single line intersection between the handle and point of the sword being swung.

Of course, this is where animations will intersect and not really respect any boundaries of the meshes involved, since that information is simply unknown.

For what it’s worth, this is often good enough.

Root Motion Animation

The issue with in-place animation is that it assumes that other systems will take care of moving the character, and this movement won’t reflect the animation. An alternative is to let the animation also drive movement using root motion. This takes the animation information on the root bone (often a hip bone or a point between the character’s feet) and lets it drive the parent transform for the character being animated. If you have something like a zombie that’s staggering, causing asymmetrical movement between different steps, this is a great way to make a character move exactly as the animation is indicating without having to painstakingly tweak numbers in a state machine.

Animated Combat: Synchronized Animation

Since we now add movement to the mix, we often need to take better care of our attacks. If a root motion-animated character attacks, there may be a forward step or lunge as part of the animation, and we could risk overstepping the actual position of our enemy. If you have played Red Dead Redemption 2 and accidentally stepped past a hitch post, only to have to turn on the spot and flail around to get the right angle to interact with it, root motion is part of the cause.

To resolve this, we can either manipulate the positions involved by moving either the attacker or defender to where it needs to be to get hit (many games do this), or we can play an opposing matching animation on the defender and synchronize the results between attack and defense. This means that we need to make a lot of animations, but it’s also a predictable way to represent our fighting and a very common way to represent melee in content-driven games. Attacker swings from the right mid-step; defender parries to the left and takes a short step back. Looks great, and solves many of our problems for us.

Motion Matching

Imagine that you don’t have just a few root motion animations, but a whole library of them. Thousands, maybe tens of thousands. If you do, you can put them into a giant search tree and feed player controls directly into this search tree to generate a matching animation based on exactly the data being fed into the search over time. At a very high level, supplemented by neural networks and other code shenanigans, this is how motion matching works. A marvellous technology, but its applications for melee combat seem somewhat dubious.

Layering

If we could only use one animation at a time, that would be problematic. If the character is carrying some kind of mission item in their off-hand while fending off attackers, we’d suddenly have to make a whole new set of animations to be able to fight while holding that item. Enter animation layers. Game engines can usually blend animations together from multiple sources using some kind of masking or layer blend weights. That way, we could override the off-hand completely to hold that mission item, but keep the rest of the animation as-is.

This sometimes leads to artifacts that don’t look great, such as weird hip rotations because of an upper/lower body blend, but it saves us from duplicating work unnecessarily.

Kinematics

Since the skeletal animation we use is limited to the premade content we have made, no matter how much or little we actually have access to, we sometimes need to compensate programmatically. This is typically done using a combination of the original source animation and additive kinematic logic. It can be used on feet to make sure that they follow the ground, or it can be used on hands to make sure that they pull the leaver or pick up the thing correctly. You can look at it as taking the source animation and making post-process adjustments to it.

There is a whole range of techniques used to achieve this, with Inverse Kinematics (IK), Forward Kinematics (FK), and Forward And Backward Reaching Inverse Kinematics (FABRIK) being the most common.

Animation Events

Something most game engines allow us to add are script cues called animation events. These can be manually placed and given functional names to let us hook into them. Commonly to provide hooks for when a foot hits the ground, so we can add footstep sounds and road dust particles, or to say that the sword swing is reaching its apex at this point and we should turn the blade “on” for impact detection.

Animation-driven Gameplay

The simple fact is: if we want animated characters, we need to start from the animation and we need to work from the limitations of that content. Some games accept this as design fact and they let the animation drive gameplay. The result of this choice is that production becomes more predictable, because we can plan out all the animations we will need, but it’s also the reason why we have to wait for animations to complete in so many types of melee combat gameplay.

Gamepay-driven Animation

If you reverse the relationship, you can drive animation with player input instead. If you think back to the root motion-type of animation, which is the exact opposite of this, imagine what would happen if the root keyframes were dictated by player input. You’d be controlling the “hip” of the character, perhaps, and then the rest of the animationw would have to adapt. It would force the animation content to be blended based on how fast the player moves and which direction they are moving in.

This is sometimes seen in certain types of games, like Carrion for example, where you play a blob that is adapted to its surroundings. But it would be interesting to see more of it.

The Dark Side of Skeletal Animation

Animation systems are amazing. But here’s a tricky fact: they’re made for animating individual objects. If an object suddenly holds or attempts to synchronise with another object, we are opening up for a million gameplay problems. If you’re crazy enough to have one of your characters sit in a chair or opening a door, it’s practically armageddon.

This is because animation systems are isolated. Anything you may want a character to hold or interact with, you pin it or parent it to a part of that skeleton. But the skeleton doesn’t care. It’ll just play back its keyframes as if nothing happened. No matter how much layering or transform parenting you do, you will always have to contend with this. Not to mention that the animation has no awareness at all about the game environment it is part of.

This clash is what sometimes gives us everything from “clipping” to the many common collision problems that we’ve simply learned to live with. It’s something you will have to be aware of if you make melee combat games.

Character Representation

With all of that animation nonsense in mind, we can figure out how to represent our character. We know that it’ll have a skeletal mesh with skin and skeleton. We know that it’ll have keyframes of animation that we can blend between.

Humanoid

A bipedal humanoid is the default for most game engines. Many animation systems use this assumption for some of the built-in functionality, such as being able to retarget one keyframe onto another skeleton. What this means in practice is that any character you want to represent that isn’t bipedal will most likely have to have its very own systems for everything.

You may also want to make humanoid variations, for example with long hair that is skinned and represented in the skeleton, or characters that miss one arm or leg. Anything that breaks the standard needs to be built or accounted for programmatically.

So ask yourself some questions.

- How many legs?

- How many variations, and which variations?

- How many poses?

Attachments

With the character represented, you have to consider what attachments you want for it. The most common ones are probably weapons and armor.

Some skeletons, you’ll add special bones for these attachments and make sure that they are animated correctly. A “right_hand_prop” bone, for example, that you can always attach weapons to. Others, you’ll animate the weapon as an integral part of the character.

The easiest is to make as few changes to the skeleton as possible and instead make exceptions on the engine-side, which is where many of the problems noted before come from. Figure out how much overlap and clipping you can accept, and then figure out which attachments you want to make.

Hit Detection

Lastly, at least for our purposes now, we need to figure out how we want to do hit detection. We’ll revisit this again later, from the weapon’s perspective, but for now you need to figure out which areas of a character can be hit and a way to communicate this.

Some ways you can represent weak points on a character’s mesh:

- Vertex colors. Maybe red represents bleeding, green represents bone damage, and blue represents armor.

- Texture mask. Same line of thinking as with vertex colors, but using an external asset.

- Collision volumes (“hit boxes”) attached to the bones.

- Joint proximity (a ‘joint’ being the intersection between two bones).

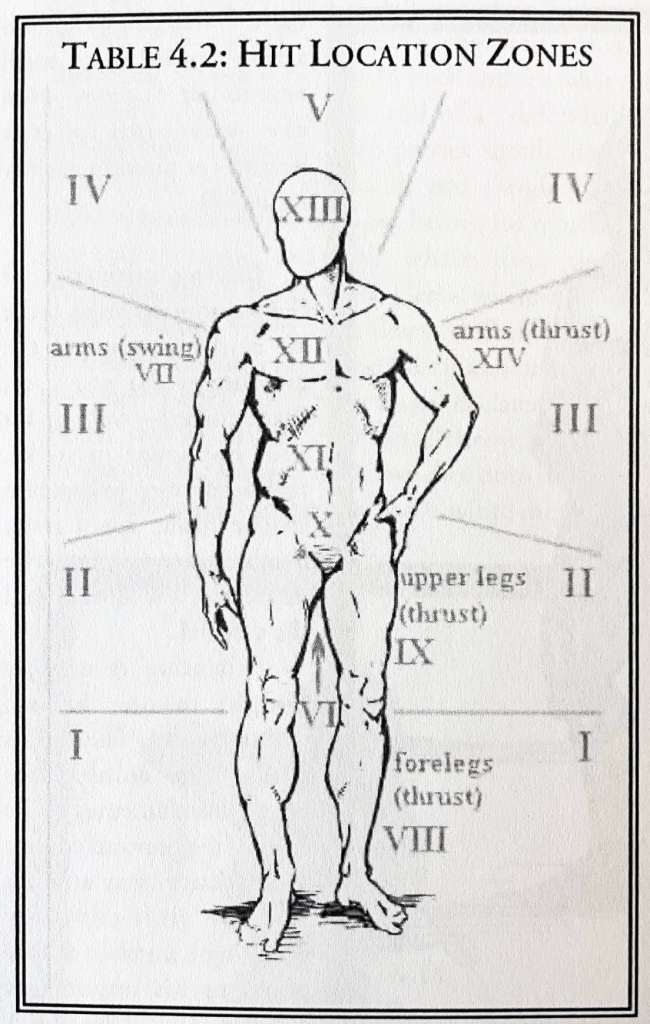

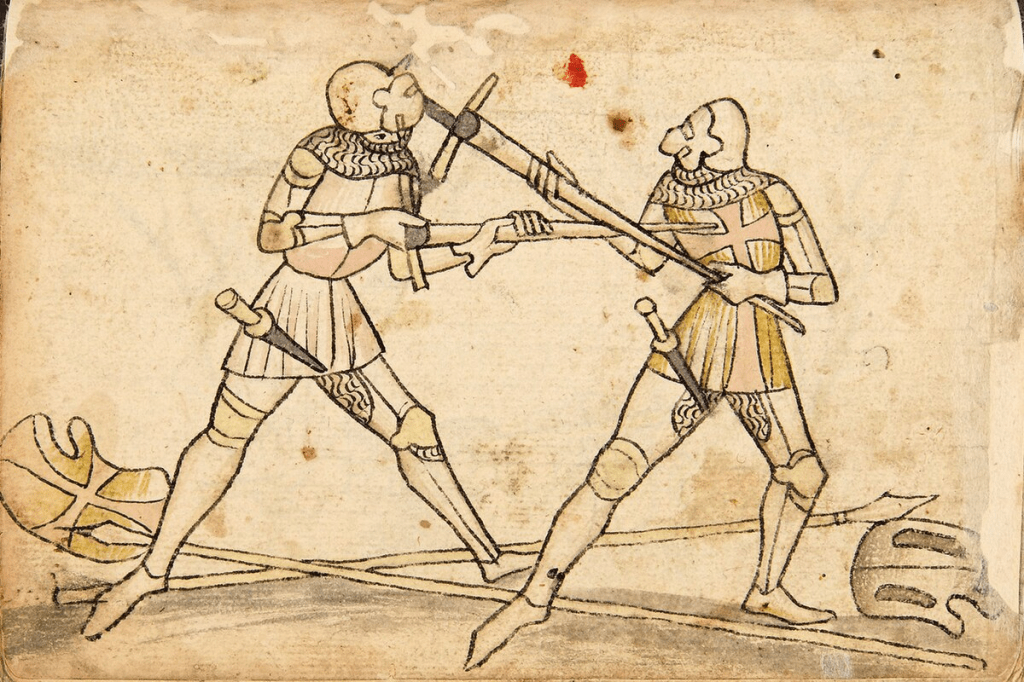

- Attack direction (inspired by something like the diagram below), where you can use an attack’s angle against a theoretical centerpoint mid-torso (near the navel) to determine hits.

- Mesh collision. Something you can also resort to, even if accuracy won’t be what you want it to be: just do a mesh intersection test between the character mesh and the weapon hitting it.

Weapon Representation

We know who we will be stabbing by now. Next is to figure out what we’re stabbing with. The implement of destruction. The weapon that you see is very rarely accurately represented.

Frame Time

One of the most common ways to represent a melee weapon is to use not the weapon itself but the frame time of the attack animation. When the animation is about to reach its apex, you turn the weapon “on” for damage purposes and if whichever other system you chose to use detects a hit, you deal damage with it.

If an attack animation is 120 frames long (four seconds at 30 FPS; animated frames, not game frame rate), maybe frames 78 to 94 are turned “on” this way, leaving the telegraphing and idle return as-is.

This can be used for more things than damage, as well. Maybe frames 94 to 110 allow you to string a second attack into a combo of attacks, and maybe you are yourself extra vulnerable to damage at frames 100 to 120 when you are returning to the idle state.

Frame time gives you a lot of room for balancing, and is a very common way to represent melee attacks.

Trace or Cast

A slightly more in-depth version of melee attack representation is to use intersection tests. Physics engines usually call these traces or casts. You can use a single line intersection test from the handle to the tip of the blade of your sword, or multiple rays out from your mace head. What they all have in common is that, when an intersection is detected, this causes a hit to be registered.

In most cases, since we tend to make really fast animations with few frames, intersection tests like these must be predicted forward in time or risk suffering from the same accuracy losses as fast-moving physics objects. For higher reliability, you can perform sweeps based on attack velocity and weapon shape rather than multiple traces.

Furthermore, what actually starts and stops the intersection test is still often frame time.

Collision Volume

We can replace the traces or sweeps with a simulated physics collider if we want. It can be a compound object, where all parts of the weapon are individually represented (crossguard, blade, pommel, etc) and individual collisions are handled differently, or it can be a single box or even mesh collider enveloping the blade.

This method is very common in rapid prototyping, since it’s typically fast to implement in popular third-party engines and makes intuitive sense. But it’s one of the most unreliable ways to represent a weapon because of the inherent unreliability of physics engines.

One potential advantage is that we can use the collider for our sweeps, since we then have a ready-made shape available. Another potential advantage is that we can gain other benefits from the physics system, such as enforcing zero-penetration or applying sliding collision against armor etc. We can also detect when to play sounds, different material properties of impacts, and so on. So it’s certainly not without its benefits.

Defense

We now have characters and weapons. The next thing to represent is defense, since no one willingly just stands there and gets stabbed. At least no one sane.

Some games don’t actually care about defense. Defense is just a flat number (like Dungeons & Dragons‘ Armor Class), and then we take turns (IGOUGO) attacking with all our fighters while you wait for your turn and keep your fingers crossed that you will have some units left to hit back with.

This is fine, if it’s what you want. But if we want to make realtime gameplay, we need to consider other aspects of defense.

Guards and Stances

Many games differentiate between “stances” based on player choice. You can switch to the X stance or the Y stance, sometimes as a counter against specific enemies or to get access to special attacks. It can also be the defensive stance and the offensive stance, for example.

It’s a good place to start since it can be part of telegraphing a character’s intent in a way that’s hard to do in a fast-paced action game. If an enemy switches to a certain stand, I can know what to expect.

Parry

Using my own weapon to defend against an opponent’s weapon is really the norm for most melee combat. It’s what fencing is all about. In games, it can be completely automatic, based on a held state (like holding the direction away from your opponent in many fighting games), or it can be an active interaction I must do with correct timing. It usually requires that switch from offense to defense actively in one way or another.

Block

Using a shield, chair, or whatever you may find and that you can put between yourself and your opponent can be referred to as blocking. Blocking attacks is not the same as parrying, since you’re not using your own weapon.

Interrupt

Hitting someone with a quick attack to stop them from finishing their heavy attack is a common feature in melee combat games. Particularly content-driven games, where you can learn which attacks are faster. Whether this means cutting them down or merely forcing them to pick a new strategy varies between games.

Riposte

In fencing, a riposte means (roughly) parrying and then hitting the opponent back using the successful parry as an opportunity. Many games, probably as popularised by Demon’s Souls and later Dark Souls, place the riposte at a specific skill-based moment between animations. If you execute a successful parry, you can then step forward with timing to execute a riposte.

Dodge

It makes sense that one of the best ways to not get hit is to avoid getting hit. Dodging means stepping out of the way of an attack before it connects. In boxing, moving your upper body away is called a fade. You can fade back from a punch and then use the distance to lean into a punch of your own.

In the Soulsborne vein, many games use a long animated dodge roll where the character throws themselves out of the way of an attack almost like a soccer goalie trying to catch the ball before it hits the net. This makes great sense in games where stamina economy is a thing, since it’s a clearly exhausting maneuver, but real world melee combat is a lot more subtle than this.

Footwork

We still haven’t attacked anyone. But we’ll get to that in due time. We now have stances, defenses, and representation of weapons and armor. Next we need to know how we move. Before we do, we need to know what the environment looks like, but I will touch more on that in a future post on combat drama since staging and therefore level design is more tightly connected to a game’s narrative context. Assuming it has one, of course.

Push and Pull

The most fundamental layer of any melee combat in games is push and pull. Push means moving towards an enemy, pushing them before you and taking the ground they previously held, while pull is backing away from an enemy and pulling them towards you. These different situations are often tied to content, and the boundaries of the arena where you are fighting will play a central role in how much of each you can do. Push too far, and you back your enemy into a wall. Pull too far, and you get backed into a wall yourself.

As you can tell, if we have a long dodge roll we need the space for, getting backed into a wall is not great. Likewise, if the enemy has a huge shield they can use to block our attacks, pushing them into a wall probably won’t do us much good as it doesn’t provide us with an angle of attack.

Note that by having different enemies require different measures of push and pull, you can easily create variation.

Circling

A common game design trope for melee combat is circling. You will lock on to a target and your sideways movement will then be relative to that opponent, effectively letting you move in a circle around them. This can be a way to communicate information by displaying the selected enemy’s health bar and armor values, or it can be a way to eliminate directional input from the combat. I.e., you don’t need to point in a direction if the game’s lock-on system is doing it for you.

Circling can also be more systemic, for example if you side-step in such a way that an enemy’s main hand can’t swing a weapon because of a wall that gets in the way (something you can do in Dishonored). It’s an interesting feature and one that is often used in film to provide room for one-liners and storytelling.

Positioning

Lastly, footwork allows you to improve your positioning. What this means depends on the game, but it can be anything from closing the distance to get close enough to use a powerful finishing move, or far enough away to use your much longer spear from a safe distance. It can also be to place yourself behind an enemy to backstab them, or above an enemy to do a drop takedown; and so on. There are many games that provide combat advantages based on positioning.

It’s not uncommon for a melee combat gameplay loop to look something like Circling->Push/Pull->Positioning->Attack; then back to Circling against the same now slightly wounded opponent or a new opponent.

Which tools you have for this and how long each exchange is depends on the game. Some games will have sprint mechanics, forward lunges or jump attacks, and other ways to change positining very quickly or to incporate positioning into the attacks themselves. For example when you attack with the energy sword in Halo: Reach, and the validity of the lunge attack is communicated by your reticule turning red.

Offense

Finally, we get to the stabbing and strangling. Just a friendly reminder that we’re still stuck with skeletal animations at this point. We’re talking about design now, but the artifacts of game engine choices from our ancient past still haunt us.

Punching

There are games that default to fisticuffs when the player has no gun ammo or lost all their other weapons. But there are also games, like The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay and Breakdown that focus a lot more attention on the punching. If you want some good inspiration, these games are excellent places to start.

Kicking

Kicks have a special place in gaming and I bet if you did a graph of current indie immersive sims underway, there’d be a higher number of them with kicking features than without. Maybe the best kicking game is Dark Messiah of Might and Magic. One of the innovative gems that acted as a precursor to the Dishonored series. In that game, the world was full of spikes and hazards that you could kick your opponents into.

But at the same time, few things are as hilarious as kicking with both legs at the same time in Duke Nukem 3D.

Swinging

Swinging includes the standard modus operandi for swords, axes, halberds, and many others. You sweep the weapon with the dangerous end intent on impacting your foe. It can be a quick attack hefting the weight of the weapon itself, or a long overhead swing like the sword equivalent of a haymaker. Many games allow you to put more or less power into your swing attack by holding a button.

Thrusting

Thrusting with the intent of pushing the pointy end of your weapon into your opponent’s body. This can be the point of your sword, the tip of a spear, or something else. Games tend to portray this as a more lethal but trickier attack to time right. Maybe partly because it’s a hard attack to do well with synchronized animation. It’s easier to just let it intersect and deal a bunch of damage.

Throwing

If you have weapons like throwing axes, javelins (throwing spears), shuriken, molotov cocktails, and so on, the act of throwing them will have to be simulated as well. Games generally don’t use physics here but interpolate between throw and hit instead, guaranteeing that a knife hits blade-first for example.

Grappling

Grabbing on to an opponent is another melee combat staple. In boxing, thaiboxing, and variations of those, you’ll see the “clinch,” where the fighters hold on to each other both as defense and offense, to deliver knee strikes or headbutts, or to block the same. With the takedowns we’ve mentioned, this can also be a way to drag an enemy close to stab them with a knife, or to hold on to their weapon and disarm them.

It’s rarely seen in video games beyond those modelling the aforementioned martial arts, since it’s a very tricky thing to do well. Synchronizing animations between characters at a distance from each other is hard enough; if you push them into immediate proximity you’re multiplying all the clipping and physics intersection issues by 100.

Hit Detection and Effect

We have pushed forward, the opponent has failed to dodge, and we’ve swung our sword against their neck. This is where we end it all! Detecting that the weapon has hit, and making something of it.

Hit Point Bashing

The probably most common way to represent melee attacks is to simply count some math at this point. We know from the frame time or intersection test that the weapon has hit, we hand over to the gameplay mathematics to deal with the rest.

Maybe the calculation is [((Strength + WeaponDamage) – Armor) * NormalizedVelocity]. Character has some strength value, the weapon deals a certain amount of damage, and we then multiply by the normalized velocity of the weapon. The total is deducted from the enemy’s hit points, health, or whatever we call it.

We can add as much as we want here. Maybe we have damage types, with different resistances and immunitie. An enemy that is immune to Piercing attacks doesn’t take any damage from the thrust we just did. An enemy wearing a specific armor maybe reduces our Chrushing damage by half.

The reason this type of system is so extremely common is that it’s simple. We can take all of the complex subtleties of our combat gameplay and externalize it from the engine. We can balance all the numbers in a neat spreadsheet with all of the formulas represensted, and we can then use whatever tools we prefer to simply put it in the game and know that it works.

Systemic

What we can do instead of simply deducting points using a formula is tap into the Stim/Response-relationship between our objects, or some other model we prefer. The weapon “injects” its stim, state, or however you prefer to represent it, and has then done its job. Whether this leads to a bounce against armor, a thud against hard wood, or a deep bleeding gash is up to the object that gets hit.

As with all systemic approaches, this requires that we have more than just the contact system in place. We need other systems to pick it up, do something with it, and also be clear enough to show the player what happened.

These complexities are why we don’t get as many of these solutions in our games. It’s harder to predict, and it’s harder to balance. But on the plus side, it’s also much more modular and using the same kinds of principles as I presented in the Building a Systemic Gun post, you can make a highly dynamic melee combat system come to life as well.

Damage

The widely played Dungeons & Dragons tabletop role-platying game got its start in wargaming during a time where simulation was a big deal. Many games model damage not just as a loss in points but as a set of consequences.

What follows here is some inspiration you can consider, no matter if you prefer a systemic approach or hit point bashing.

- Balance: damage dealt to balance won’t kill, but will make the enemy fall.

- Morale: damage to morale may make an enemy yield, surrender, or flee.

- Move speed: damage to move speed could be based on hitting the legs, and would make positioning easier against the enemy.

- Stun: temporarily stunning the enemy may mean blinding them, dazing them, forcing them to perform a delaying action (such as removing a caltrop stuck in their feet), etc.

- Feature damage: can allow you to attack the enemy’s features in one way or another. Cut off the dragon’s tail and it can’t lash you with it; disarm the enemy and it can’t hit you with the weapon, and so on.

- Bleeding: cause the enemy to bleed, suffering damage over time. According to longsword fencing instructors I talked to, this was what you often died from on the battlefield, and you weren’t always aware of it until it was too late. E.g., you were technically “dead” already, but you’d keep fighting for several more minutes until succumbing to the circulatory shock.

- Movement: feeds back into the push/pull and positioning dynamics, but many games will have weapon impacts that allow you to push enemies back or pull them towards you.

- Dismemberment: cutting off limbs is often a visceral animated response to when you kill an enemy, but some games use it as a feature damage of sorts. You cut off the right arm, they don’t have the sword anymore. It can be brutal and gruesome, or it can be the black knight from Monty Python’s Holy Grail.

- Death: of course, death is the typical outcome of damage. But it can also be more specific, like if you hit an enemy in the head, heart, or neck, and they instantly die without you having to whittle them down.

- Lasting effects: some damage could be stored and given lasting effects. If you keep cutting your enemies’ heads off, and they learn about it, maybe they’ll start wearing gorgets. They should!

Style

You may feel by now that we haven’t really talked design yet, just technology. But it must be reiterated that the technology will be what sets the boundaries for your designs and this is why it’s relevant.

But what style of melee do we want to have? We can take inspiration from the types of melee in the first half of this post, but let’s also fit the gameplay into our design. Why do we use melee?

Control

Some games use melee as a way to exert control over the field of battle, or to gain access to the next area in a level. You must kill the guards before you can open the door, or you may kill the guard so that no one will be monitoring the security cameras.

Control works best when it’s an optional feature. A permission with clear restrictions that may affect the conditions of the currently played level or even a future level you haven’t played yet.

Duelling

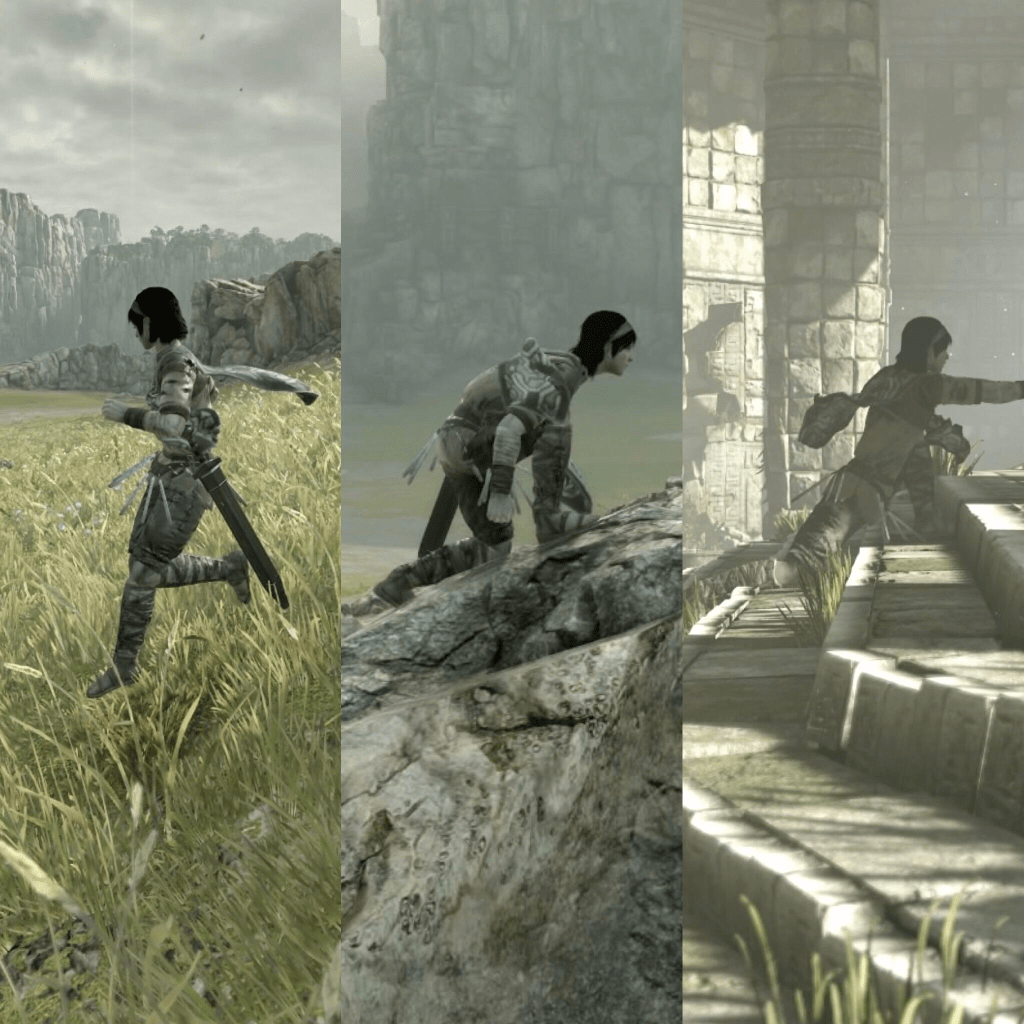

With animations the way they are, it’s often easier to animate combat between only two characters, or at least two characters at a time. This makes duelling a great fit, and everything from the brilliant jedi duels of Star Wars: Dark Forces II — Jedi Knight to the intense one-on-one fights of Severance: Blade of Darkness, this is a deep well of inspiration.

You can include pretty much every fighting game in the same context, and the player’s pursuit of understanding not just of the content in the game but of the spirit and skill of their physical real world opponent.

Mass Combat

If you care less about synchronizing your animations correctly, and you want volume of enemies, you can let the player be Sauron from the intro of the first Lord of the Rings film: one swing, and dozens of enemies are defeated!

Impact effect may become less important and instead you may model the morale and effect of whole warbands clashing against each other. Mount & Blade has these types of fights, where each fight is certainly tense and interesting, but the massed battle as a whole is the focus.

Choreography

The next thing you can consider is more choreographed play. A single hero fighting multiple foes and winning the day with neat cinematographic tricks, and often comedy as well. This lends itself well for content-driven games where you can have contextual animation triggers.

Imagine a well in the center of a market square, and when you kick someone they fall into it with a nice animation while playing the Wilhelm scream. That’s the kind of thing that’s choreographed, and though it can certainly be triggered by a system, it’s not systemic in any practical sense.

Flynning

The style of fencing developed for Errol Flynn’s old adventure movies, like Captain Blood that was mentioned in the post on combat philosophy, is still called Flynning. It’s melee combat that isn’t about the combat at all but a way to portray characters in an action-filled environment. Rather than trying to kill each other, the actors are actively hitting each others’ swords to the loud classic clangs of blade on blade that we still use for swordfights in cinema.

Games don’t do this as much, but the insult-based swordfighting of The Curse of Monkey Island is probably the best version of it that we have in games!

Conclusions

This post got a life of its own somehow and extended way beyond the comparatively simple and more pseudocode-heavy outline I originally had. But I think there are good reasons for this. Just like video game dialogue is essentially the same now as it was 30+ years ago, melee combat in games has become somewhat predictable.

As with so many other things in game design, we forget that we can do anything we want and end up copying the tried and true solutions from the past five years’ financial successes. This means that a new more systemic way to do melee combat would have to start from design.

My hope in finishing this post is that it may inspire someone to do something and then go ahead and release cool games that innovate game melee combat!

Or, as usual, you can disagree with me in the comments, or e-mail me at annander@gmail.com.

4 thoughts on “Combat Melee”