Systems generating emergent outcomes or interesting synergies; it’s what most of my blogging is about and my one true passion in game development. Gamification, on the other hand, is usually taken to mean using game elements in a non-game context. Often to keep you engaged by using points awards, competitions, and reward mechanisms of various kinds.

Gamification is huge. We see it in educational platforms and apps like Duolingo and the Khan Academy. We have gamified apps interacting with our smartphone step counters, geolocation software, banking, and much more.

The techniques used for this in “non-game context” also dominate mainstream game design. To better understand (and have stronger opinions about) how gamification works in game design, let’s look at how it’s evolved into what we have today. The second part (next month) will then summarise it all with a brief overview of how you can implement it.

I’ll leave whether you should use gamification to your own judgment. (And to comments and/or e-mails to annander@gmail.com!)

Dungeons & Dragons

The first Dungeons & Dragons, sometimes referred to as Old or Original D&D (or simply OD&D), came out in 1974. Ever since, there’s been a wide range of other so-called tabletop role-playing games (or TTRPGs), but except for a brief dethroning by Pathfinder during the 4th edition of D&D, D&D has remained the biggest by far. In the U.S., D&D is synonymous to the entire hobby of tabletop role-playing. You’re not playing RPGs (or TTRPGs), you’re playing D&D. Note that no one called it TTRPG until much more recently, to distinguish it from its digital derivatives.

Experience points that gain you levels comes from here. Maybe the design landscape would’ve been very different if the modern (and in my opinion ridiculous) practice of patenting game design ideas had been applied by the makers of D&D. Then every service game with an experience mechanism would have to pay a fee to the estates of Arneson and Gygax, and maybe wouldn’t be slapped on every single game arbitrarily.

You gain experience from two things in OD&D: killing monsters and finding treasure. The amount of experience depends on your character’s abilities and the relative challenge you had to overcome. For monsters, it’s the level of the monster compared to your character level. For treasure, it’s based on the level of the dungeon you are currently exploring. If you kill a level three monster or find treasure on the third level of the dungeon, you will get the unmodified monster experience reward or treasure gold piece value as experience. Find 1,000 gold pieces, gain 1,000 experience. Kill a five hit-dice (level 5) White Dragon while at level five, and you gain 500. You can never gain more than this, but you will gain less if you are tougher than the opposition or if you were unlucky when you rolled up your character.

If you have a high score in your character’s Prime Ability (Strength for a Fighter, for example) you gain a 20% bonus to experience points awarded. A low score can give you up to a 20% penalty instead.

We can refer to this as a kind of challenge economy: depending on how dangerous the opposition you dare push yourself towards, whether venturing deeper into the unknown or facing tougher opposition, your rewards will also be higher. But there is no reward for pushing too far.

The second prominent economy from OD&D is a kind of resource economy. Spell slots, torches, spendable coins, food rations, and so on. Things that makes it feel like an expedition, with all of the logistics involved, but also balances how much you can do and generates stress when you’re starting to reach the bottom of your backpack.

One aspect that doesn’t always survive in the various translations is the value of time and time as a resource. Gary Gygax is often quoted for his “detailed time records must be kept” comment, and you can clearly see where this comes from in the original rules. In the rules for exploring dungeons and the wilderness in OD&D, you play out turns which are each 10 minutes long. You need to spend some turns resting, and you can only cover a certain amount of ground in a single turn. Torches only burn for a set number of turns before you need new torches. Each turn that passes also has a risk to cause an encounter with a wandering monster that you need to sneak past, trick, or fight.

Can you venture into the next room of the dungeon, or should you make the trek back to the surface first to spend some coin and stock up? Quite obviously, games like Darkest Dungeon goes deep into this dynamic.

Diablo

We’ll go past the D&D-based dungeon crawlers, since I’ve mentioned them many times before. Since I don’t know them well enough, I will also skip over Japanese ARPGs; but the influence of games like Secret of Mana is actually quite important. Just left for someone with better insights to explore.

Instead, we skip forward directly to Diablo. This game started out as a game styled around the original Rogue (what we’d insist on calling a “roguelike” today), where player turns tick an internal clock but the game stands still when you do nothing.

At some point during development, after having already decreased the time of each turn many times over, the Diablo team decided to decrease it even further, all the way down to fractions of a second. The clock also ticked constantly instead of waiting for the player to do something. They had effectively made Diablo a realtime game. The first western-style Action Role-Playing Game or ARPG (to the lament of computer mice worldwide).

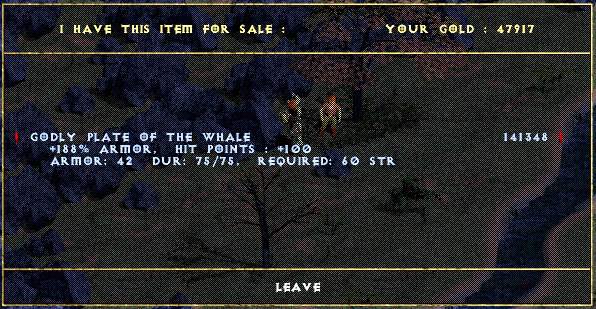

But what gamers will remember isn’t the new mode of play—they never do—it’s the game’s reward structure, further refined in the sequels. A chase for loot, the use of procedurally generated dungeons, and the use of keywords in combination for both enemies and items. Diablo will also be renown for the grind required to get the best stuff.

None of this is entirely new at the time, but Blizzard had a knack for taking the tried and tested and making it more appealing.

The idea of a loot economy is hardly new in Diablo. Players had been hoarding treasure for decades already. But the aspect that was pushed forward was the probabilistic side of it. The grind side, with enemies as loot piñatas dispensing just enough to keep you going and only sometimes giving you what you really want. This ties into the same psychology as a slot machine or other gambling device, which will eat your money 95% of the time. But that 5% is what you live for. At least in the original Diablo‘s time, you didn’t spend any real money in this slot machine; only time.

Procedural generation is another big deal, but something I’ll talk about more in-depth in a future article. Diablo made clever use of keyword generators, constructing items based on loot tables with adjectives and nouns, creating a dispensing of well-foiled loot that pushed people not only to play more and click faster, but also to find ways to “dupe” (duplicate) loot and cheat the system with trainers and hacks. Foiling in this instance doesn’t refer to characters, of course, but to the contrast between finding lots of crap items before finding that one really cool magical one that stands out next to the crap.

Future Diablo games will push this even further, not to mention the loot economies of MMORPGs. Virtual item economies are here to stay.

Stats

There’s a good chance that no one remembers this game. Maybe I cheated back when I played, or my memory is off, but my strongest memory is that you could upgrade all your values in an unhinged way as you levelled up. After a few levels, you could jump up on top of buildings!

This is another feature that has been around for some time by this point, particularly for Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs) where the concept of the three main roles was established: Tank, Healer, Damager. To optimise your role, you’d have to get and equip the right gear, unlock the right abilities, then combine with other characters in just the right way.

Of course, the idea of a progression economy comes from OD&D, with your numbers improving over time. But digital games in all their forms will explore it even further. With additional features, like perks, feats, and various forms of things worth unlocking at higher levels, this creates multiple layers of customisation and character optimisation. Kind of like deck building in Magic: The Gathering, where you are trying to optimise your deck by combining cards with powerful synergies.

Not to mention the item sets, gear customisation, gem slots, and myriad other statistical variations that come about through the further refinement of these concepts. Enter concepts like min/maxing and character builds, driven by a desire to make the best possible characters tailored either for making a game easier or for doing the best possible job in a multiplayer group.

Achievements

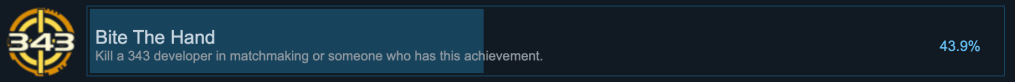

Something happened with the launch of the original Xbox Live service in 2002 that would change the psyche of gamers possibly forever. It introduced Achievements and the concept of Gamerscore. Since then, dedicated websites for the tracking of achievements have become many. Steam added achievements styled after it in 2007.

There are many different schools for achievements, and most games combine all of them.

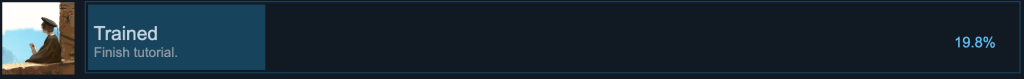

First of all, you have progression achievements, which unlock as you play the game. They can be hidden or public information, depending on whether they could include spoilers or not. Many times, they’re least-effort achievements, and you can sometimes unlock one merely by starting the game for the first time or completing a short but mandatory tutorial.

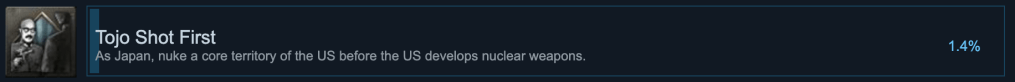

Another way to do achievements is to reward them for highly specific results that are hard to achieve; I call them replayability achievements. Paradox’ grand strategy games tend to do this really well, as an example. They play with the historical context they take place in, both indulging alternate history fans’ “what if”-cravings and providing the hardcore completionist with greatly increased replay value.

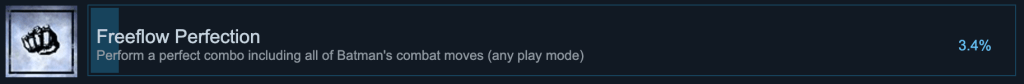

The next type of achievement is arguably where the concept got its name in the first place. Performance achievements; a reward for managing to do something that’s hard to do.

Another type of achievement is the opportunity achievement, which can only be unlocked under certain circumstances that the player may not have full control over. It can be to do a certain counterintuitive thing while playing a mission, for example, or maybe to kill someone from your own Friends list in a multiplayer match.

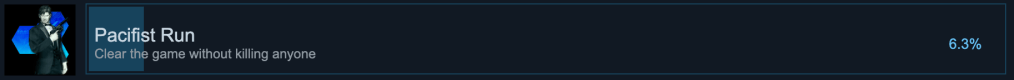

A variant of the opportunity achievement is the restriction achievement, which can be to either complete a specific mission without using some features, or even to finish a whole game without said feature. It’s a somewhat more tangible type of achievement, because it applies hard requirements to how you play the game and isn’t entirely abstract.

The final type of achievement I’ll simply call the chore achievement, and it’s the one that has you do something some arbitrary number of times. Usually a multiple of 10, for some reason. Kill X enemies, collect Y thingamajings, discover Z new locations; you know what this is about.

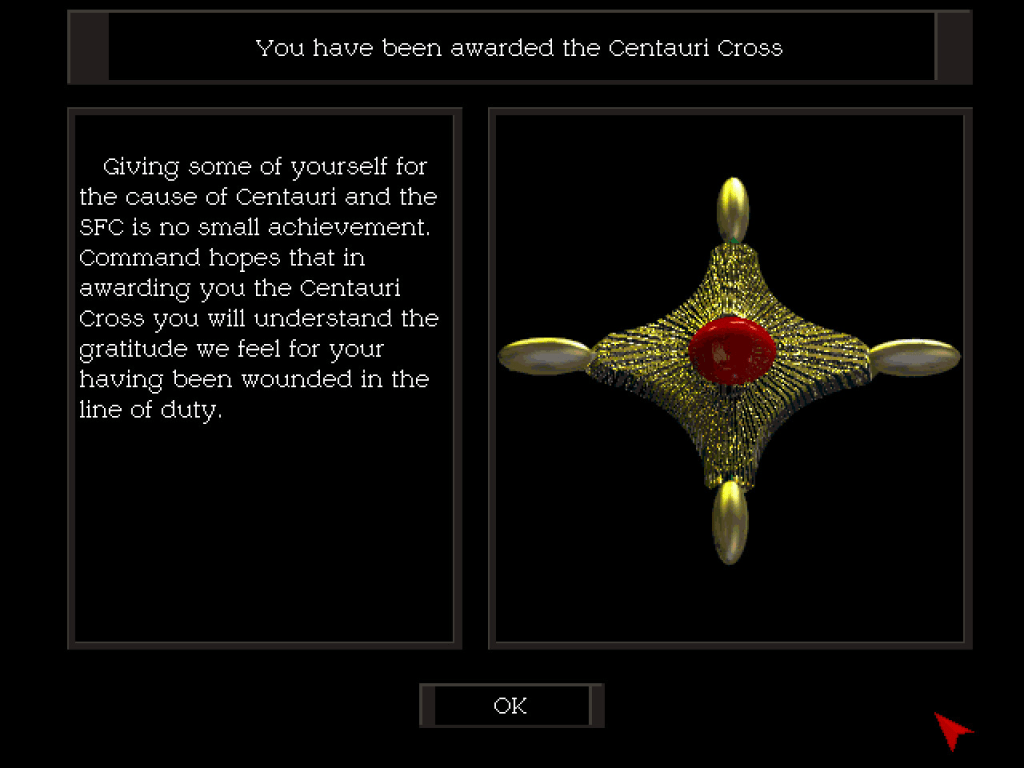

Of course, achievements as we have become used to them are external rewards without any form of diegetic connection. Our game world avatar—the character we play—has no connection to the achievement because the achievement doesn’t exist in any meaningful way in the game world. This doesn’t have to be the case, however. In Looking Glass’ often overlooked tactical shooter, TerraNova: Strike Force Centauri, you could be awarded medals for certain actions in the field. A diegetic form of achievements that had real connection to your interactions within the game.

If this was done today, each medal could be an achievement also, to provide an extra meta reward for the player.

World of Warcraft

Other games developed the subscription-based and scheduling-heavy models that World of Warcraft (WoW) was based on, but this game is where it really takes off into the mainstream. The designs of WoW are predominantly there to keep you playing for hours upon hours. The most obvious reason is that they want you to keep paying your subscription. Subscriptions can be considered the first steps gaming took into monetisation.

This introduces an entirely new economy: time. Your time; the player’s time. Many of the dynamics in WoW are built to waste your time. Queues to get into a server, timed cooldowns for abilities, scheduling mechanics where you need to wait for certain in-world events, dailies, weeklies, monthlies. Not to mention the restriction that you couldn’t originally get an animal to ride (a “mount” in the game’s parlance) until you reached level 40. A considerable time investment.

All of this goes into a time economy. But there is a crucial social aspect to this as well, which is what pulled most people in. You’re playing with friends, or finding new friends, and the game became a reason to hang out and meet new people from across the globe. Social activity is one of those things that we rarely see as “wasted” time, since it rarely is. But in the meantime, you kept paying WoW‘s monthly subscription. Whether you did that to get a new mount, finish the game’s raids with your guild, play with friends, or meet new friends, is of course entirely up to you.

Something else that shows its head around WoW and other MMORPGs is the meta economy. Buying and selling characters. Paying someone else to “farm” gold or experience points so you can buy it for real money. A market that’s rarely condoned by the companies offering the service, since it risks changing the in-game dynamic. Also, Blizzard doesn’t get a cut.

Of course, wanting to get a cut is what will lead to Blizzard exploring the controversial real money auction house in Diablo III.

Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare

We’re used to gamification by the time Call of Duty (CoD) abandons the world wars for ghillie suits and irradiated Ferris wheels. But CoD changed everything once more. It brought D&D‘s systems back, kicking and screaming, into the parts of the mainstream that wasn’t already playing World of Warcraft.

The fast pace and highly accessible and rewarding nature of CoD 4′s perk system, for one thing, made it immediately understandable and rewarding. It was fun to get a few last shots in with your pistol after being killed. It was fun to get kill streak rewards and to keep building your available feature set while playing the game.

With a constantly increasing number of players playing online, but not necessarily playing with friends, CoD 4 comes out when “alone together” is becoming a thing and all its gamified systems fit so well with this that many of them have stayed with us since.

I would even go so far as to say that the launch and popularity of CoD 4 is something of a defining moment for video game “gamification” practices, particularly for competitive multiplayer games. It’s not alone in this development, but it’s pivotal.

Free to Play

There are some big proponents of free to play design whose talks you should listen to. The three most prominent ones are Teut Weidemann, Nicholas Lovell, and Amy Jo Kim. Outside of the game field, you should also read and listen to people within the behavioural sciences field. For example scientists like Dan Ariely, who wrote the brilliant book Predictably Irrational, and whose effect on our in-app shopping can’t be overstated.

But in the gamer sphere, you won’t hear those voices. You’ll hear more negative voices and encounter some deeply entrenched groups who fight against concepts like pay-to-win and content gating. People who will say that free-to-play games aren’t real games, or even that free-to-play game design is inherently evil. Let’s ignore this specific side of the conversation for now, and instead look at how gamification changes with free-to-play dynamics.

World of Warcraft and other subscription-based games already started on this journey years ago, but free to play design turns monetisation into a practical goal. It explores how to turn players into spenders by making the gamified system not just a gamified system but a machine that turns people into superfans willing to spend real money on what has at that point become a hobby and not “just” a game.

The most natural part of this transition is to put a monetary value on time. Something that the meta markets around WoW already did, like we mentioned before, when people could start charging you for in-game gold or experience grind. The concept of selling a ready-grinded Level 60 character in WoW may have been frowned upon by Blizzard; with free-to-play it becomes a product on ssale. (It’s a product on sale in WoW too now, directly from Blizzard.)

When a game is free to play, this lowers the barrier of entry considerably. But you will then have to consider concepts like conversion rates, meaning how many players go from free players to paying players. If this number is too small, your free game won’t be sustainable. Particularly since many such games require server infrastructure and continuous live support.

So even though the idea is that “non-paying players keep paying players playing (and paying),” there’s a caveat buried in creating a sustainable business with a low barrier of entry. If you don’t attract enough players, you won’t convert enough players into paying players, and you won’t build superfans.

To simplify thinking about free to play, just picture all the different kinds of in-game economy we’ve covered, and then put a cash price on it. Usually in the form of a virtual currency of some kind. Gold in World of Tanks, for example.

The cynical side of free to play design is that it often ends up gating the parts of games that traditional gamers engage with the most, for example using friction dynamics like requiring you to spend in-game resources to retry a failed level or to wait for 30 minutes before something completes. Unless you pay. It’s also not unusual to offer things for sale that provide balancing advantages to paying players, called “pay to win.”

Free to play, as a simplified definition, puts a real money price tag on the grind and various economies that gamers have engaged with for decades.

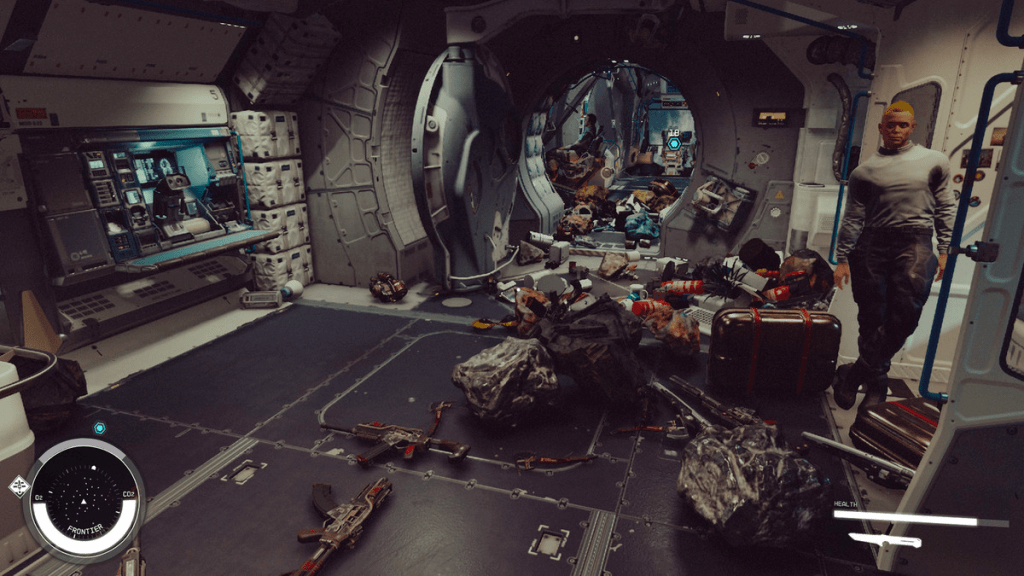

Games as a Service (GaaS)

Many free to play games are also service games, but not all service games are free to play. Games as a Service (GaaS) is a different sort of beast, where the game is pushed more as a continuous live service provided by the developers. The most obvious example is probably the Fortnite battle pass and the various season and battle passes it has spawned since. Even if the battle pass was originally a DOTA 2 innovation, where part of the cost was put into a prize pool.

The disadvantage of the Fortnite-style battle pass is that it requires a steady stream of content. Near-constant, in fact. Players will chew through this content much faster than it can be produced, forcing developers to crunch to keep up. The service being provided by GaaS needs to be kept fresh.

Games like Minecraft and Star Stable instead opt for weekly releases of new things for their communities, arguably approaching the service aspect of GaaS in a different way.

But it all ties into the same “superfan” line of thinking as free to play games in general. You want to keep the players engaged, and you do so by pushing ever more content into your game.

The parts that are unique to GaaS are mostly exclusivity incentives, where you can only get specific rewards by participating right now, and then they’ll fall out of rotation from the current battle pass. This gives rise to a kind of timing economy tailored to trigger people’s FOMO. Weaponised community building.

Crafting Systems

I’ve now named many different kinds of economies that games use to “gamify” their experiences. One of the key elements to any virtual economy is the principle of diminishing returns. To make sure that there are more avenues to get Money Out than there are ways to get Money In (as a player). One way many games approach this is using crafting or upgrading systems where you may need three of the first thing to create one of the next thing, and then you’d need three of that next thing to create one of the thing after that. And so on.

This motivates you to pick everything up that isn’t bolted down and keep combining things into other things. It may even motivate you to care about the “crap” loot the game dispenses on a routine basis.

This is part of where game economies can become quite cynical, since you must remember that all of these virtual economies are designed for exactly the effects they have. Granted that some systems aren’t balanced enough on launch or miss their mark unintentionally, but all of the restrictions and diminishing returns you have probably become used to by now were put there for a reason: to act as systemic sinks for your virtual cash.

Last Words on Gamification

Gamification ties into many different tools of many different trades. Gamers often take sides for or against some of these practices, usually illustrated through the lens of one particular game that they feel strongly about.

Many people I know refuse to acknowledge that World of Warcraft used and still uses many of the most vicious gamification practices, for example, simply because they wasted half their teenage years on that game and accepting that it was a service game throughout its life cycle puts many other things into question. Better to not rock the boat.

I don’t really have a strong opinion about any of these practices. People engage with these games for myriad reasons and there are great games in all categories. Times also change, whether you want them to or not, making it meaningless to rage against it. How today’s gamers perceive value has changed drastically from when I was buying big box PC games, after all.

But I do have one big gripe with many of the popular reinforcement loop dynamics we see today in both free-to-play and premium games: they remove player agency. They promote a play style hinged on following directions and checking off boxes.

Player agency is a tricky thing to talk about. If we imagine a free-to-play reinforcement loop with level up systems, virtual currencies, scheduling mechanics, and so on, you will usually have lots of things to do and you can usually pick which one to do at any given moment. They may not feel like they lack player agency as you play. But there is something at play here that turns the player into a consumer rather than a participant—and I want to dig into it before wrapping this up.

Curiosity

This is really the heart of why I think gamification harms player agency: gamification kills curiosity. If you don’t get any points, items, or achievements for the thing, the thing doesn’t matter. When the whole game is built around extrinsic rewards, you lose the player’s intrinsic motivation along the way. There’s simply no room for explorative curiosity in such loops. It becomes a “content treadmill” for both players and the developers. (More about the content treadmill in a future post.)

In mission-based games, this often takes the form of working off a checklist of activities in a menu rather than exploring the game world or any emergent features. It’s also common for service games to rely heavily on repetition, and the fifth or even fiftieth time you hear the same narrative beats repeated you are no longer listening.

Narratives vs Player Stories

This is the classic difference between what happened to my character and the consequences of what I did. Games like The Last of Us will always display the same story beats and never invite the player’s choices, while Baldur’s Gate III touts the many hours of alternative cutscenes that result from the combinatorial explosion of its branching choices.

Games motivated by a narrative will hinge entirely on the quality of the narrative, while games built on player choices and their consequences can become almost anything.

There’s no real room here for service games, however. Whenever you build a game that relies heavily on a virtual economy and repetition, the narrative becomes less important (except for players playing “alone together”), and the player story becomes more about the endgame and completing the battle pass than about what’s happening in the game’s simulation.

Anecdotal, but I have friends who played countless hours of World of Warcraft, and would always tout it as such a social experience. But one time, when I was visiting a friend as they were wrapping up a WoW session, all I could actually hear were conversations about in-game optimisations like DPS, cooldowns, and so on. The social interaction was mostly about the game’s meta, and not really “social” the way I’d use the word.

Doesn’t mean they weren’t having fun, of course. But it’s something else than an emergent player story.

To Gamify or not to Gamify

Some of my favorite games have elements of gamification in them. Every D&D-derived video game of course completes the circle of inspiration by using experience points and levels. Most of the eminent immersive sims also have such elements, even if they may attempt to tie them more directly to in-game systems.

I personally think the drive to make more content and fewer systems is an unfortunate but fairly clear effect of gamification. But unlocking things, gaining points, and accumulating virtual wealth, are still entertaining features worth your while, regardless of whether you intend to “monetise” it or not.

What’s Next

This is the first part in a series on gamification. Continue reading Part 2: Implementation if you want, or jump straight to Part 3: Loot.

4 thoughts on “Gamification, Part 1: Origin”