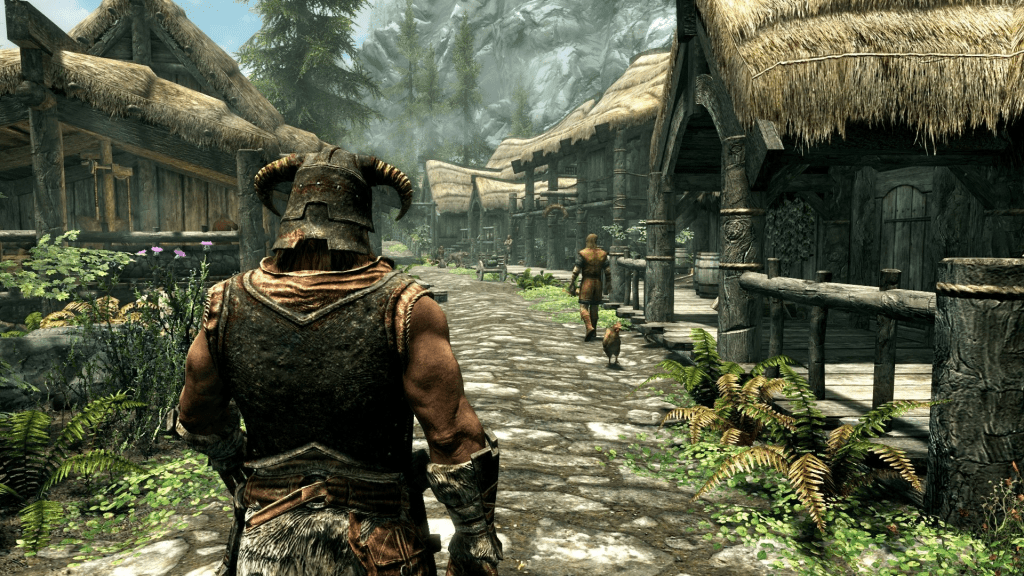

The past few years prove that there is a market for premium systemic singleplayer games. Few have listened to us (developers) when we tried to pitch such games for the past decade. Or ever.

This isn’t because there is some kind of conspiracy against systemic games. Not at all. Systemic designs are very hard to sell. Not just to publishers or to customers; systemic designs are hard to sell even to your own team. We get caught by our own excitement, or we try to sell technology or tools as if they are designs when they are really not. The fleeting nature of systemic design feels like losing control, or like a potentially bloated mess of optional sandbox content that we have to make for the simulation to be complete but that will add little for the average player.

In this post, I try to address pitching systemic games, based on my own mistakes.

Pitch Composition

There’s a wealth of literature on how to sell something. Including how to make a good sales pitch. For this post, we’ll stick to a very general high level idea of what pitching needs to achieve, and leave all of that expertise to the real experts. One great book you can take a look at is the book Pitch Anything, by Oren Klaff.

For this post, let’s assume a pitch needs to do three things:

- Convince the party you are pitching to that a thing is worth making. A value proposition.

- Also convince them that you are the ones who should make it. Establish your credibility.

- Cater both messages specifically to the people you are pitching to. The packaging.

Value Proposition

The origins of AAA (or “triple-A”) is from credit ratings. It stands for a rating of low risk, high reward. Or, in the terms of investment banks, “exceptional creditworthiness with minimal risk of default.” It was used in early game development, including pitching, to signify projects that were safe bets with high financial potential. Today, AAA is used to describe anything from team size to budget size.

Like many of the terms we use in game development, it’s become almost meaningless, or at least the interpretations have become too varied for consistent use.

But these origins are relevant. When you pitch something, the value proposition still needs as small a risk as possible with as big of a potential reward as possible.

The Ask

Pitching is to ask for something. It may be funding to get your game across the finish line, developer buy-in to make the next feature, or something else. Be specific with what you are asking for and you will have a less frustrating conversation.

- Financial security: If your project fails miserably, maybe doesn’t even get released, they will usually soak up the loss while you simply move on. This part is rarely said out loud, but it’s a key ask nonetheless.

- Funding advances: The most obvious ask towards publishers and investors: getting a chunk of change that pays for development. Just make sure to make it realistic and not low- or high-balling your numbers. Say how much you need and why.

- Commitment: Asking for your team to commit to your project or to key changes. This can sometimes be the hardest pitching you’ll do. Even more so if your team has low morale.

- Marketing help: Getting help marketing your game. Be specific with this ask, since some partners may only do the minimum if you don’t have a concrete marketing spend that is contractually obligated. Be clear with your ask. It’s not uncommon to match marketing spend with development spend.

- Technical support: Server architecture, cloud infrastructure, console porting, and other elements of development that are beyond your capabilities as a developer and therefore included in your ask.

The Gains

When you pitch, you must offer something to the people you are pitching to. Money, ownership, future commitments. It’s not enough to offer them a potentially great game, you need to show how it’s more than the sum of its parts.

- Cash: Unless you are unable to afford asked rates or you are making a very big ask from a busy partner, you will rarely have to pitch as much if you have cash to spend. But it’s definitely a gain to be considered. If you pay for something upfront, you will rarely have to part with things you’d rather keep.

- Revenue: There are more ways to share revenue than there are stars in the sky. It may be time-limited or permanent, the percentage may shrink or grow over time, and the share may or may not be taken from one party to compensate another (advance on royalties). If you want to offer revenue share, you should provide a revenue projection based on real data. One that shows how large the earning potential is in multiple scenarios, for example based on number of copies sold. Just be realistic.

- Equity: Instead of potential future profits you can offer ownership. It can be ownership in your company, or a newly founded company that handles this specific project under mutual conditions with investors. Equity allows someone to have a bigger stake in what you are doing and will of course mean that they get a chunk of future profits also. Just be careful to part with too much equity.

- Property: You can offer up the intellectual property (IP) you are creating. Your game, its characters and likenesses, assets, etc. Usually including everything related to it, such as potential sequels, merchandise, tie-ins, and more. I’ve been told you shouldn’t accept deals like this today, but it may be on the table and you may not have much authority to say no.

- Exclusivity: Something that will often be heavily implied anyway, but not always formalised, is exclusivity: that you won’t be launching on more platforms or making more than one game at the same time. This is less relevant today, where platform holders seem less inclined to pay for exclusivity, but depending on who you are talking to, it’s still something worth considering. It can be forever, it can be time-limited, or have other restrictions. But offering exclusivity can be valuable.

The Risks

Game development comes with many risks that you must address with your pitch. You don’t have to call them out and tell people what your solution will be, but you should consider them and hold yourself accountable for them.

- Delays: explain how you plan to deliver your project on schedule. Almost every game project suffers from some kind of delays (for no good reasons). Sometimes those could’ve been foreseen, planned for, or even mitigated. This is really where your credibility comes in. Convince people why you won’t suffer those delays.

- Complexity: this is where many systemic designs fail stakeholder scrutiny. They will look or sound complex or complicated, and may imply scale that is not actually required.

- Inexperience: if there are things in the project that you haven’t done before, or technologies you need to evaluate and research properly, you have to be very transparent about it. If your whole team hasn’t delivered a game before, this is a major risk that you must be able to address.

- Time constraints: release windows, budget timeframes; there can be multiple reasons why your time is constrained. Perhaps you can’t start fulltime until you get the third programmer onboard, and that won’t happen until six months from now. Bring out a concrete timeline that you can safely commit to.

- Non-Compliance: the game may become something else than what you agreed on, for creative or financial reasons. Smaller, larger, or styled differently than intended. This is where most creative differences will come from, since many signed deals will be commitments and you’ve just chosen to break them. This is the main reason you’re likely to have milestones and other deliverables along the way, so that any accident about to happen can be course corrected.

- DOA: the game may be dead on arrival, missing its target audience or simply failing to gain traction against other launches in the same window. In the best of worlds, this doesn’t just kill your studio, but provides at least six months to a year of time where you can do your best to salvage or improve the situation.

The Value of Systems

The systemic value proposition is extremely tricky. For many external stakeholders it’s not the same as the creative argument or the design paradigms.

Many stakeholders want replayable content that’s cheap to make, and will read “systemic” as making content production easier or cheaper. Perhaps using procedural generation techniques to generate multiple levels from a small set of content, thereby not needing as many level designers or prop artists.

This is not the same as systemic design at all. Systemic design is about letting go of authorial control and allowing players to have the fun. This almost invariably makes a systemic design sound more expensive to make, since it implies a high degree of freedom and a sandbox nature.

If you detect excitement around systemic ideas, be really careful to note what is generating the excitement, or this could be the fundamental misunderstanding you’re experiencing.

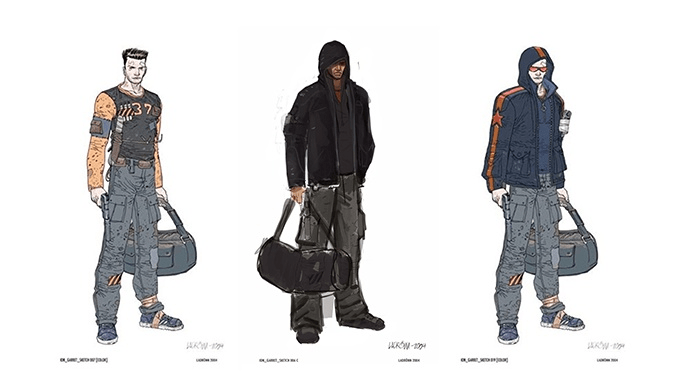

Credibility

Anyone can have ideas but everyone can’t turn ideas into games. You must be able to prove why you should be the person making your thing. What to lead your credibility pitch with is tricky. For systemic games, it helps to demonstrate technical expertise immediately. To line up all the key roles that will address the risks you’ve already mentioned and explain how you’ve filled them.

Studios You Worked At

Studios may get a lot of attention after releasing games that sold many copies, attracted many concurrent players, or gained high scores in reviews and good media attention. Though this front row attention may be fleeting in the media, it will matter a lot for your credibility to be part of these journeys. People may even talk about the best place to be at a given time.

If you’ve mostly worked as a salaried employee, your studio pedigree will be the most important thing you can offer to state your credibility. It also tends to be the first thing many will ask to know.

If you worked at particularly big modern studios, you mention which roles you held and not just the name of the studio. This is because if your title was Junior Assistant to the Senior Assistant’s Assistant, your impact was probably quite small, and talking about this studio doesn’t actually provide much credibility.

Years of Relevant Experience

Simple maths. If you have fewer years of experience, you have probably learned less. But the keyword here is “relevant.” If you are pitching a big sprawling open world role-playing game after working on first-person shooters for 15 years, people may believe that you know how to make games, but may be weary that you haven’t made this type of game before. This will then become a risk that you must address.

Something that’s almost a joke at this point is to sum up the experience of your team and use that in your pitch. E.g., “250 years of combined gamedev experience.” You can of course do this anyway, but it doesn’t really mean anything.

Games You Shipped

The easiest and most quantifiable way to demonstrate that this isn’t your first rodeo (if it isn’t) is to list the box art for the games you shipped. If this is a very long list, you can stick to the ones that were important or are more likely to be known by the people you are pitching to.

Similarly to studio experience, you may want to specify what you did on each game too, but only if it becomes too anonymous otherwise. You shouldn’t turn the credibility element of your pitch into a reason to talk about yourself at length.

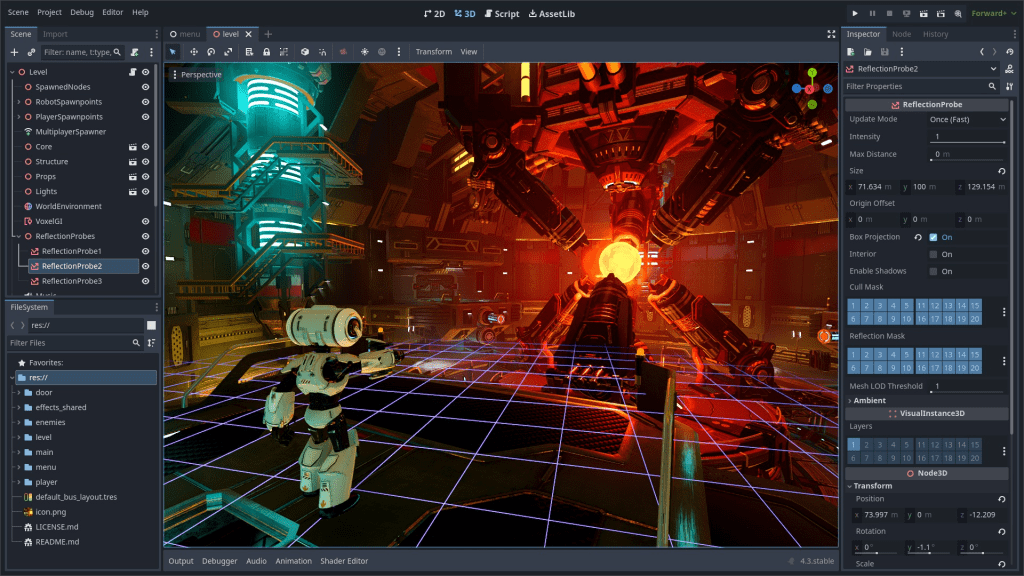

Choices of Technology

For an external stakeholder, technology that exists and has been proven through previous game releases is worth a lot more than experimental technology. For this reason, technology becomes part of your credibility.

If you come to a pitch and you say you are working on your own engine that will probably be finished a couple of months ahead of release, this will send off warning flags for everyone in the room. But if you say that your team is working with an established third-party engine and you have a working prototype already in place, this will give a much better first impression.

Team Shortlist

It helps to have a team already lined up and waiting for your go-signal. A team shortlist is a list of people who have agreed to let you put their name down for if you find the funds. It’s very rarely treated as a commitment, more a way to lend weight to a pitch. It’s better than saying you’ll start recruiting when you have your funding, but it’s not as good as having people already onboard.

Packaging

The packaging refers to how you communicate value and credibility. There’s no right or wrong way here, but it will matter a lot based on who you are talking to.

Preparation

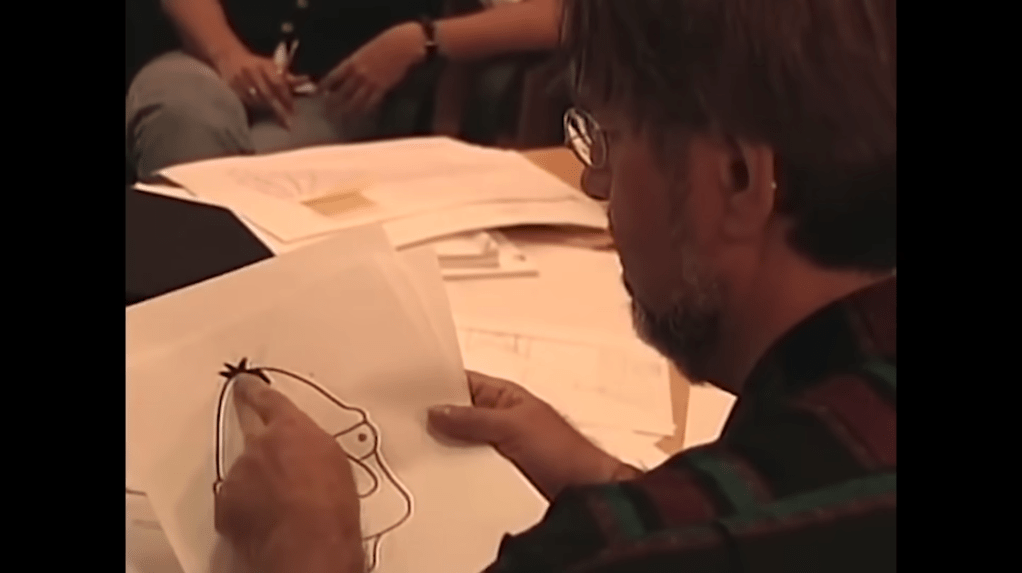

According to the It Was a Sh!tshow podcast, Futurama spent two to three years in preparation before it was pitched to studios. During that time, they explored characters, key art, technology, and many other things.

In game development, we rarely have this room for pitch or concept development. But you do need to prepare as much as you possibly can. You need to figure out the risks, foresee what potential stakeholders will be worried about, and proactively respond allay their concerns.

Story

Stories resonate with people. Introductions, reversals, and climaxes. Presenting your pitch as a story doesn’t mean you should lead with your game’s story, it means that your whole pitch should be a story with a proper beginning and end. Start with a bang, end with a call to action.

There are some pitfalls you should avoid, however. Don’t ask open-ended rhetorical questions, e.g. “Have you ever thought about why dogs have two ears?!” Because chances are that they only confuse people and don’t actually make them think the way you want. Take charge of the story and walk through your pitch’s narrative beat by beat. Leave nothing to chance.

If you want to frame your pitch as a story, use video and visual aids as much as possible and let the story come from you rather than the pitch deck.

Metaphor

A strong metaphor can also carry a pitch. In an interview with Designer Notes, games venture capitalist Mitch Lasky talked about his EA pitch using a container to illustrate the benefits of standardisation.

Metaphors can of course be traps as well, if they in fact illustrate something you don’t intend, but you’ll figure that out as you work through it.

Use a strong metaphor if it fits your whole pitch and doesn’t leave strange questions.

Novelty

A sad fact is that no one wants novelty. Novelty almost always looks like a risk more than a gain. From Railroad Tycoon to The Sims, many of the most groundbreaking games through the years had few fans in management. Similarly, Markus Persson (“Notch”) said that no publisher would’ve cared about Minecraft if he had pitched it to them: it could only happen by selling it directly to players. You can absolutely lead with how your game is different and new, but be aware of this risk.

Only focus on novelty if you can incorporate a strong why into your pitch.

Content

I have a whole post that laments the use of the word “content.” But it’s enough to say that it’s a word often equated with quantity and used by both developers and consumers. Developers will talk about how much content they offer, while consumers will usually ask for more of it no matter how much is on offer.

Most systemic games are not built to funnel “content” to users. Churning out downloadable content (DLC) fits really poorly, and most of the time replayability is a matter of smoke and mirrors. Choosing A instead of B, or approaching through the secret door instead of the main entrance. Functionally, the very same content, but a different experience.

Some systemic games manage to pull it off, like Prey and its excellent Mooncrash DLC, but at other times it ends up feeling artificial and a bit forced. Thief wouldn’t benefit from offering you a special gold-lined blackjack, for example. It would only risk diminishing the core experience.

Therefore, if you want to offer a systemic game, don’t pitch your game on its quantity of content.

Good/Bad

People generally use harsher words than good or bad. What often gets lost is the reasons why we think something is good or bad. Particularly when good or bad is applied to specific parts of a game, such as its story or gameplay. If you didn’t like the gameplay, maybe this made you dislike the story. If you really loved the premise, then maybe you felt better about the gameplay than it actually deserved.

This means that good or bad is mostly a loud declaration of opinion that muddles any real qualities or faults of the thing being touted. If you disagree with the zeitgeist effectively countless “masterpieces,” the gamer population is quick to call you an idiot.

Publishers may not call you an idiot, but you should still avoid calling things good or bad. It may even be that the thing you’re trash-talking is something one of the people you’re pitching to happened to work on.

Therefore, avoid value terms and comparisons to other games.

Buggy Janky Messy

There are many words for this. Janky, buggy, glitchy, broken, even unplayable. Some game companies have gained a reputation for their games feeling “janky,” while others may have segments that are more or less so. “Eurojank” is sometimes used as its own term.

The issue with this language is that it’s also often applied to complex games. Having to use multiple mapped controls, or using menus in certain ways, will become conversationally equivalent to jank.

No matter what you do, do not use these words to describe your own game unless it’s deeply intentional. If you are making the next Goat Simulator or Gang Beasts, then by all means call it janky. You can also acknowledge if your audience calls your concept janky, and run with it, but don’t introduce the term on your own.

Don’t talk about your own game as janky, buggy, or messy.

Technology

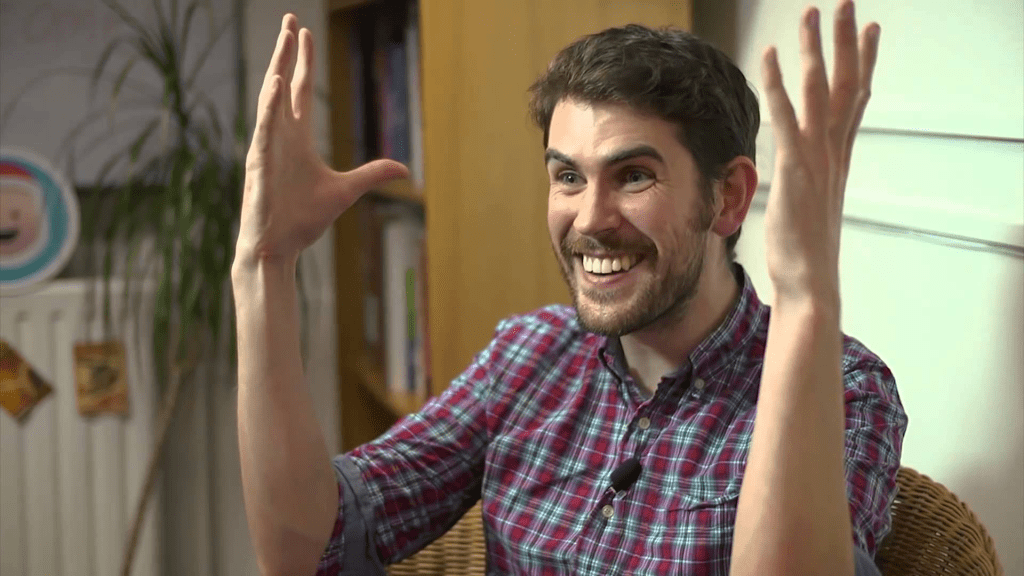

In the marketing buildup to the release of No Man’s Sky, if you followed games media to any extent, you would’ve seen Hello Games’ Sean Murray. He was the face and voice for the project and his infectious enthusiasm built a gigaton of hype. But he was also first and foremost a developer. Someone who was enthusiastic not just about what the game actually was but what it could be. A mentality that everyone in game development understands.

If you talk about technology and its potential, be careful to not promise more than you can deliver.

Don’t Use Examples

Maybe it’s because of the clickbait era and the tendency for a lot of people to only read the headlines and not the main points, using examples can actually be a problem. If you describe a general system you have and you then say that it’ll be used to generate something like a metal ball, it’ll then become the Metal Ball System and nothing else to some of the people listening to the pitch.

It’s better to provide a framework for your systems and let the audience’s imagination put things together, or you can easily fall into the trap that you need to start defending your example or expand on what makes the example interesting. You don’t want to be put in that spot. Even worse, if you use examples from other games, they may infer different things for the audience than what you had in mind.

Avoid using examples, or they may become people’s most concrete takeaways.

Building Excitement

Let’s get one thing perfectly clear: you can’t convert your own excitement into a signed contract. Excitement is important when you deliver your message, since we’re social beings, and it can definitely affect your believability and how compelling your message is. But in every other way, your excitement is strictly yours.

No one cares about your deep lore, the motivations of your characters, the 1,000 years of world history you wrote for your fantasyland, or anything else of that sort, until after they have crossed what I call the excitement threshold. At that point, everyone won’t care, but a subset may suddenly care to the point of obsession.

For every player that praises all the well-written logbooks and audio journals, there are nine others who completely ignore them. For every publisher rep you talk to who loves the cool technical solutions you’re talking about, there are nine others who have never seen Visual Studio and will simply not get what you are trying to make.

For every complex systemic thing you added to your prototype, there will be someone at the other end of the table who asks why the shadows look wrong or why your prototype doesn’t look as visually polished as the one from some other pitch they just saw.

All this and more is bound to happen, and you must learn to really read the room when it comes to which parts of the message to focus on.

Raiders of the Lost Ark

As an example of the excitement threshold, take a look at the original trailer for the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark. Note how this trailer focuses, not on the Indiana Jones we know today, but on the mystery of the Ark of the Covenant and its terrifying implications in the 1930s. Lost artifacts, Egyptian ruins, and nazis: as pulp as it gets.

Compare this to a modern trailer for the same movie. A trailer that focuses clearly on all the character flaws and iconic shenanigans that many of us remember fondly from the original movie.

This illustrates the difference excitement makes. In the original trailer, no one cares about the character of Indiana Jones. We don’t know him yet, or why we should care about him. But once the second trailer hits, and the movie is now renamed Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, it’s all about Dr Jones, his fear of snakes, and those cool scenes that we all remember.

This comparison is important, because most of us will be facing what Raiders of the Lost Ark faced: an audience that needs to have something else to latch on to than what you want them to be excited about. An audience that doesn’t know Dr Jones yet and will have to discover him on their own.

The same goes for our pitch — you need to treat your audience (the stakeholders) to something that excites them. If you can do that, you’ve won half the battle!