The goal is to allow the player and their avatar to occupy the same emotional space.

Harrison Pink, Snap to Character: Building Strong Player Attachment Through Narrative

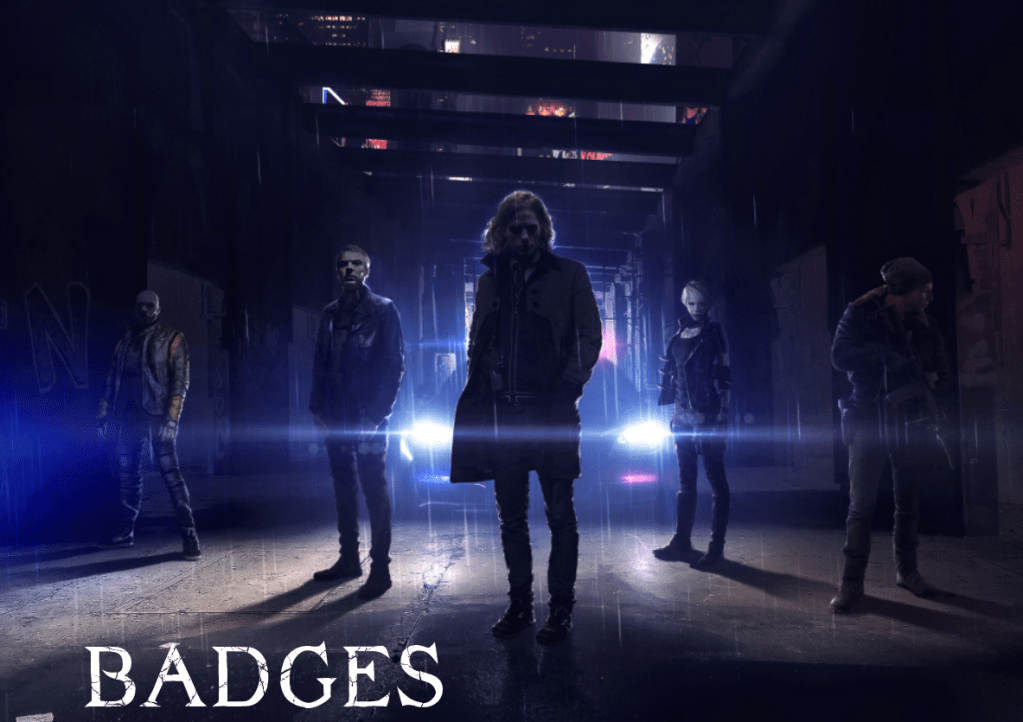

At Graewolv, while exploring the concept of the demon-powered first-person shooter, one question that kept nagging at my brain was who I was actually playing and why it led me to shooting people and interacting with demons in the first place. It bothered me that this didn’t have a straightup answer, or at least an answer that could make it comfortable to “occupy the same emotional space” as the character I played.

Shooting people can be fine in a military shooter. “You’re a soldier following orders” usually works, even if it carries significant historical baggage. But when put in another pair of boots it feels weird. Shooting people becomes murder.

Joel in The Last of Us murders some of the few remaining medical experts in the world in cold blood. He is written well enough — and we get enough time to sympathise with him — that we can still see Joel as the good guy. In any attempt at an objective analysis, he’s a selfish psychopath, but we can understand his motivation and pick his side over that of the nameless doctors in the game. In fact, I’m somewhat bothered by how easily some players can say “I would’ve done the same.” But in the end, we feel like we know Joel, which makes us side with Joel.

I wanted this to be resolved for VEIL too. You commit despicable acts of violence and this needs to be motivated so that the player doesn’t get uncomfortable occupying this emotional space and so that the violence doesn’t become too gratuituous.

These lines of thought made me look at role-playing as a design tool for exploring game concepts further. In this post, I’ll cover how I worked with it. Hopefully it can be interesting to other game designers out there. It’s a tool I still use whenever there’s a chance to do so.

If you’ve done similar experiments, I’d love to hear about it. Write a comment or e-mail me at annander@gmail.com.

Note that some of the stuff I’m about to share in this post is the property of Graewolv and is shared with their kind permission. Special shoutout to the incredible David Brochard, who drew all the concept art.

Wishlist VEIL on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2436490/VEIL/

Join the VEIL Discord server here: https://discord.com/invite/7JxqcDZ9Pq

Background

I started playing roleplaying games around the age of 10. It’s been my favorite hobby ever since, with a few breaks at times when life got in the way.

My approach has always been somewhat experimental, trying to find new ways of playing or just variations on existing ways, and rarely playing the same thing through more than one campaign. Experiments like building a scenario where all of the information is within the group, putting all conflicts between players, playing with multiple game masters, no game master at all, or playing court intrigues based on the assassination of Gustav III.

This has led me to focus on a number of things that I think make role-playing games unique and that makes them excellent as game design tools beyond being games in their own right.

Roleplay can be empathetic, where you try to imagine how another person thinks or feels and you act it out. You can roleplay an asshole, like playing Cyberpunk 2077 as a Corpo, because there’s a detachment between you personally and the avatar you are playing. It’s engaging to make decisions based not on your own morality, but on your interpretation of this other person’s morality. Real or imagined. This is equally true whether you are a player or a games master. Every participant can engage in empathetic role-play. It also stays true with one character on several players, one character per player, or multiple characters per player — we can still engage in empathetic role-play.

It can be exploratory, where you act out different things and find out what happens. Basically the FAFO (F*ck Around and Find Out) of role-play. Insult your friends. Kill the princess and rescue the dragon. Sail off on a ship instead of going down into the dungeon. Since the only limitation you have in role-playing is your own imagination, this element is one of the most unique that the hobby has to offer. It can also be used for more than just entertainment, such as exploring what may happen in a second Trump presidency. Exploration is related to empathy, but doesn’t have to be. It can also be purely for fun or as a method for pseudoformalised conjecture.

It can be mechanical, where you play through situations using a platform of rules to see where the rules lead. Maybe you want to have rules for detailed mech customization, for realistic firefights or fencing, for exploring the unknown, or for leveling up and unlocking new tools to play with. This is very similar to hex-and-counter wargaming, which incidentally is also where the roots of role-playing games are firmly planted. It’s an effective way to see where the game may need more or fewer choices, or if you may have forgotten something that needs to be designed in more detail.

It can also be narrative, testing or fleshing out the story or world-building. Role-playing games are extremely dynamic and pretty much all of the previously mentioned reasons to role-play clash fundamentally with the idea of a prewritten plot, but as a tool, narrative role-play is great. You can try out different villains to see how they work and see what kinds of interactions players expect, and you can work with language in interesting ways. In one test session a few years ago, the first question that came up in play was, “how do people in this world communicate?” Something the world-builder at the time (me…) had completely overlooked that became obvious through play when the characters needed to talk to each other.

Note that these four forms of role-play are not an attempt to classify or define anything, and they definitely don’t cover the full breadth of the role-playing game hobby. They are often mixed together in different ways and sometimes hard to separate from each other.

These four ways of approaching role-playing are consciously structured to answer relevant questions, and you should hopefully see the interesting space that starts to emerge between them.

Role-Play as a Tool

What the four forms help you do is push the game experience around the table towards empty spaces in your design. It helps you ask interesting questions and provide compelling answers. All of those answers won’t be what you actually use, but as a design process, role-play can be one of the fastest ways to explore your designs. All you really need is imagination.

You will be playing the characters and having the experiences you want your game to offer, without having to finish your game.

We can use empathetic role-play to sample our characters, factions, and conflicts. To figure out ways to make the world we are building or the villains we are introducing more compelling. It can also show us where our world-building may be missing something. If the hero may need a foil, for example, or if the conflicts sound a bit undercooked when put in motion, or become repetitive faster than we had anticipated.

Exploratory role-play allows us to push the boundaries and see what happens. It’s a great opportunity to let developers improvise solutions to the problems or missing designs that may come up, and essentially design the game through participation. When someone decides to kill the main quest giver, for example, that may be something the game needs to solve for. Or when a certain spell or weapon is used in an unconventional way. What’s important here is that you never say no. See where the exploration leads and make decisions after you have talked it through. Take notes, but avoid turning the play session into a meeting. The beauty of the process is that you can just throw stuff out that doesn’t work.

Mechanical role-play is a bit more tricky to make use of as a design tool, since it easily becomes a deep rabbit hole of mechanics design that are then only written for the tool and will never translate into its digital incarnation. Some of this can be worth a lot, since it can explain your intentions at a high level. But avoiding time waste is often a careful balancing act. If you focus on outcomes more than specifics, for example how many options you may choose from in customization, how much gold you make, or how much damage is dealt and taken, it’s still a valuable tool since it can hide large complex systems behind the improvised decisions of your players. You want the mechanics to be similar enough to your intended game to feel like it hits the same structural beats as your digital game would without only becoming a clunky version of it.

Finally, narrative role-play is quite useful as a tool, since it allows you to take a trip through your broad story beats and see how they connect. If something needs a higher pace, clearer clues, or other changes. In some ways, it’s like a script reading session with some additional improv. It can also make use of random generators like tables and cards to help you create a fitting story for your game or even to decide where you want the narrative to connect to procedural elements. It’s particularly useful for filling in gaps between the story beats you already have in mind. Together with empathetic role-play, you may even get to see how the factions and characters in the game interact over time, and you can surmise empathetically how the story should play out in ways that are hard to do with just a word processor.

ROLE-play

Let’s look at how to do this, in practice, by first looking at the roles involved. The avatars whose emotional space we are about to share. The role part.

If you’ve ever studied journalism, interrogation, questioning, or something along those lines, you should be familiar with the 5Ws (or 5W+H). They’re intended as a shorthand for getting to the meat of a story: Who, What, Where, Why, When, and How?

These one-word questions are extremely useful for any form of characterization, regardless of context, since they help you tell a whole story. You don’t need to answer all five at the character level. Some can be answered by the setting or through collaborative improvisation.

You can also consciously leave some of the answers blank in order to figure them out through play.

Who, of course, asks who was involved. Who did the thing, who was affected by it, and what a third party thinks about it. In journalism, three sources is a kind of golden rule: two people representing the opposite sides, and a third neutral party. Even better if you can have more than just one neutral party. This is a great way to think of scenarios for games too, since the player is often a third party engaging with an external conflict.

This was the trickiest one for VEIL, but the decision was to look at you as an occultist for hire. Someone who solves other people’s demonic woes in exchange for money and power. These “someone” were set as four specific factions in the game world, representing tradition, law, crime, and change. With those pieces in place, there was enough friction to create interesting missions.

What tells you about the thing that happened. Murder? Injury? Theft? Job opportunity? There’s another journalistic axiom that says, “does it bleed?” Because suffering and bleeding traditionally sells stories, so the more violence or trauma — or risk of violence or trauma — you can push into this, the better. Games rarely shy away from violence in the first place so simply making someone bleed won’t catch anyone’s attention. Instead, this goes into the high level activities that you’re going to engage in. Not the verbs of the moment, but the motivations behind them.

You exorcize demons and you take missions connected to that, but you also work for the power players of The City, running their (usually violent) errands. To explore this, a system for generating objectives was created. More on this later.

Where lays out the geography of the matter, so you know if you need to care or not. Closer to home tends to mean higher relevance, which is why local news papers fill a role in journalism: you care because you live there. But fantastic cities and other pure escapism works too, just not on the same instinctual level. Even with fantastical environments, it’s usually good to anchor the where in something recognisable.

The game takes place in The City. It has districts, it has class struggles, it has all the things you’d expect from a modern city but with a slightly gothic overtone. It’s Gotham City, in a way, but if Gotham City had demons from Hell instead of tragic villains with mental issues.

Why is trickier, since motives are not always clear and because opinions may differ. This kid did the crime because they play Dungeons & Dragons says one side, while the other says they were bullied in school. A consulted psychologist chimes in with something about sexual frustration. (Three sources, remember?) What we like the least is when there’s no explanation whatsoever, even if it can also make us run wild with speculation. Cliffhangers exist, after all. But we tend to more easily reach for the obvious explanation. Figuring out why is trickier in real life than for game design, because in game design we already tend to obsess over motivation. The trick is to connect this motivation to the motivation of the characters in the game world.

You’re a selfish sort of person that happens to do good by coincidence. An antihero. The reasoning behind this is that a player in an action video game of the VEIL kind, is inherently selfish. They want to get the next reward, collect the loot, finish the level, etc., and going back to Harrison Pink’s point on the avatar and player occupying the same emotional space this fits well with the goal. You pick your employers. You solve your problems. You get your rewards. The rest are a means to an end.

When isn’t fifth in relevance, it’s just how I’ve taught myself to remember these words (Who, What, Where, Why, When). It’s the time and the place, in history or the present. When can be very broad, such as “19th century Paris” or “Middle-earth in the Second Age.” It can be extremely specific; “At 03:45 last night.” If a major plot beat in your game is the assassination of a king, then when can also inform you whether something is happening before, during, or after this assassination. You can also leave when blank and figure it out through play, in case it’s one of the issues you want to resolve.

It’s not a flashback. It’s not the future. It’s the fictional world’s present, in a noirish gloomy perpetual fall season where it seems to never stop raining. (Because modern game engines obsess over real-time ray tracing, which makes reflections a thing.)

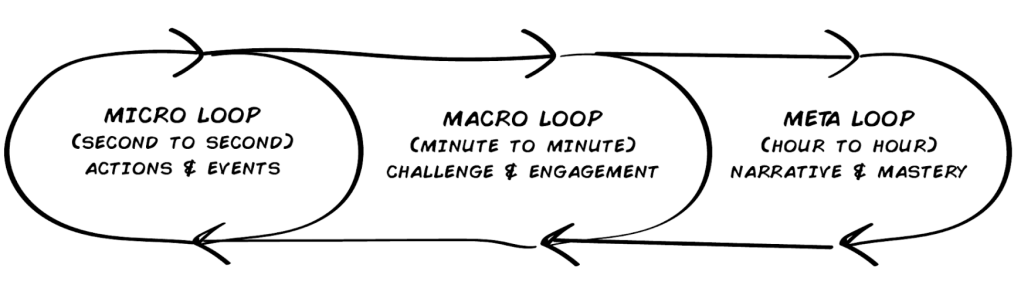

How will be the verbs. Your players’ inputs and intentions as supplied to the systems of the game, and what kinds of outputs they generate. What’s important if you want to make something interesting is to examine this at multiple levels. Your video game will more effectively demonstrate the second-to-second or micro loop of your game; shooting, jumping, taking cover, etc. But what the role-play tool can do is explore the minute-to-minute or macro loop, and potentially even the hour-to-hour or meta loop.

Shooting, summoning demons, completing objectives, failing objectives, working for the factions, introducing factions, revealing secrets, collecting ritual materials, getting tricked, etc.

role-PLAY

Now that we know the roles we will take on, we need to know how to play the actual game intended to explore them. At their core, role-playing games are formalized conversations. You talk, respond to what others are saying, and you may use some rules to generate outcomes that steer the conversation in unexpected directions.

The key differences between role-playing systems isn’t which polyhedral dice you roll or whether they take place in Narnia or Night City. It’s how truth is established and which parts of the conversation that we influence with mechanics.

Truth

Some variants of role-play use a referee, often called a game or dungeon master, that acts as a rules moderator and comes up with parts of or even the entire plot or story of the game you are playing. Others eschew this in favor of collaborative storytelling.

The key difference this makes is how truth is established.

- Authoritative truth. The game’s referee has the final say on what is true. Usually combined with one or more of the other forms of truth. In some games, the authoritative role can rotate between players or players can have authority over specific parts of the truth. Truth is established by the person(s) with authority.

- Pre-established truth. Lore. Whole geographies, histories, anthropologies, astrologies, and otheries. Can be your favorite IP, something you’ve written yourself, or what your favorite author came up with and published. Truth is established by what is written before play.

- Procedural truth. Often in the form of tables, charts, or dice rolls used to generate random outcomes, but it can also be the direct consequence of other forms of mechanics. Any entry or combination of entries could become true by rolling them at the point of generation, but you can’t know what the truth is until it’s put into motion. Truth is established by combining components in a given moment.

- Relational truth. Using relationships between people, places, or events, to establish what’s true. A hates B loves C trades with D; there’s the basis for our truth. The mechanics will typically push things, challenge things, and cause or handle conflicts of interest, but the relationships are still what are most important. If the king has an agenda, this agenda will affect what the king decides to do, for example. The agenda is true, but what the agenda makes the king do can only be decided in the moment. This is the primary vehicle for empathetic role-play. Truth is established in the moment, based on how things are related to each other.

- Situational truth. Where we don’t know what’s true in a certain situation until the situation plays out. A combat system won’t tell you who was injured until the dust (and dice) settle, just like we won’t know how casting a certain spell plays out until we’ve cast it and described its effects. We go through the motions, then we know what actually happened. Truth is established after the fact.

- Unreliable truth. Any variant of truth where the outcome can change after the fact. Maybe you roll to change it, or you collaborate, or you spend some kind of currency, or you rewind time because nah, that’s not what happened. Truth is established only after all unreliable steps have played out.

Mechanics

As mentioned previously, mechanical role-play is always at risk of wasting time if you write complex throwaway rules. Writing a deep combat system for a game that’ll ultimately be a first-person shooter is probably a waste, for example, because you are not actually solving any problems by doing so that you are not already tackling in your game engine.

For most role-playing games as tools, you need to touch on some or all of the following elements in your mechanics:

- Situations means rules for the kinds of scenarios you expect (or want) to happen in play. This can be very broad and may include genre expectations for your game, such as survival, firefights, construction projects, and so on. What’s important is to leave the potential outcomes open. A situation is the cause, it’s not the effect. It can represent the food shortage, but it won’t present for where to find food.

- Abilities describe characters. What they can or can’t do, but also as description. This doesn’t have to be detailed, but it can be. One project may need detailed lists or decks of cards that describe different capabilities, while others can use abstractions. This is the toolbox you are providing your characters with.

- Conflict doesn’t have to be armed and dangerous. It can be anything where there is a clear stake involved. Conversation, bartering, seeking aid, etc. One side wants to gain something and the other side stands in their way or needs convincing, cajoling, seducing, or other methods for changing their outlook. Role-playing games benefit from clear statements or triggers to tell you when a conflict has occured. When the first shot is fired, when the intent is stated; something to tell everyone playing that this is in fact a conflict. The clearer you can make this trigger, the better. But you can also skip this entirely, the way some screenwrights will just say “fight happens,” and then it’s up to the choreographers on the film to make it compelling.

- Scene is the moment of play, and may change key dynamics. This is where you can apply permissions, restrictions, and conditions in systemic terms. If the situation is a firefight, this is where you can add pouring rain, a particularly tough enemy, or other changes. If the situation presents the shortage, this is where you can collect the resources to solve it and where some other party may stand in your way. The scene is where it all comes together.

There are some practical ways you can approach making your test rules faster:

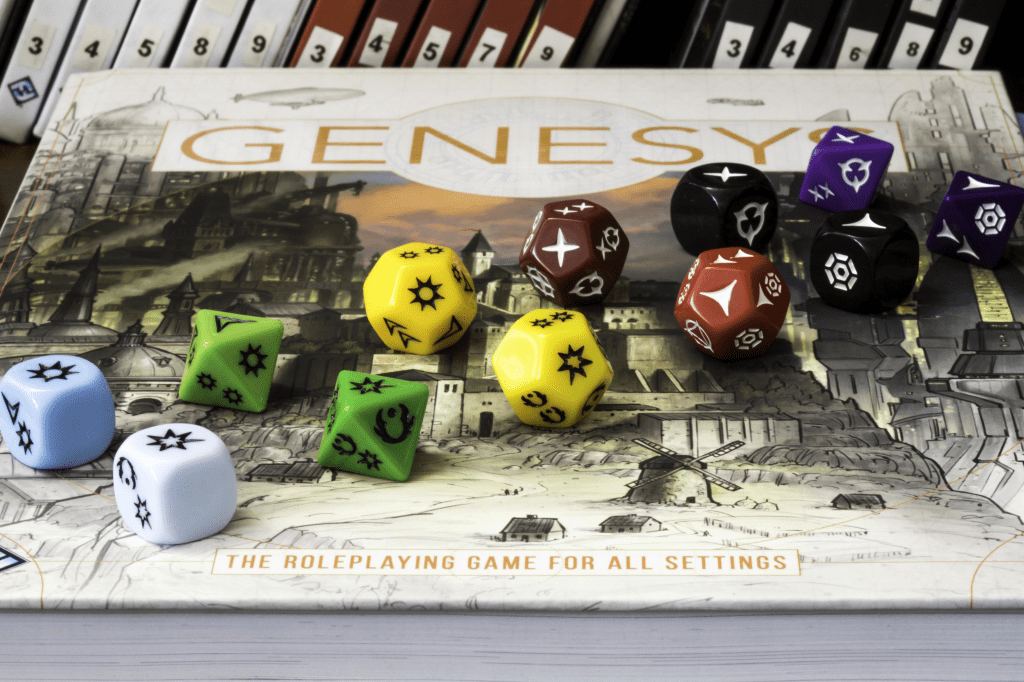

- Generic Mechanics. You can always start from a set of generic rules, such as Chaosium’s percentage-based Basic Role-Playing, Steve Jackson Games’ Generic Universal Role-Playing System (GURPS), Evil Hat’s Fate Core system, or Fantasy Flight Games’ Genesys. The simpler and more accessible the choice of rule system is, the better. Just like you don’t want to waste time building complex systems, you don’t want to waste time teaching them either.

- Proxy Mechanics. A lightweight version of using a generic system is to use proxy mechanics. This is when you take something like the combat system from Risk to represent battles, and perhaps use the cards from the board game Root to add some flavor. Using a proxy mechanic works best if it’s one that all participants already know.

- Focused Mechanics. You can also make extremely specific rules intended to model things that are unique about your game. Perhaps character customization is important to your game, and you decide to represent all the different parts with cards that let players have fun with the main ideas of this concept. Or you want to have a suppression system that allows you to force enemy AI to keep their heads down, so you model a simple rule system for only that rather than combat as a full simulation. Picking one or two things to turn into mechanics can be very effective, and lets you zoom in on exactly the things you want to explore while skipping everything else.

- Generators. Whether using decks of cards, random tables, or online generators, making use of random generators is a very powerful tool since you can construct them in such a way that they leave interesting blanks for you to fill during play.

Oathbreaker

The following example of a role-playing game as a design tool is from work I did for Graewolv on the upcoming first-person shooter VEIL. I served as Design Director for the project for about a year, in 2020-’21, and during that time it fell on me to explore the design in whatever ways I could while working on the early prototypes for the game.

It was an incredibly useful tool for me, that helped flesh out the different factions and missions in the game, and it was the key inspiration for this post even if it’s a tool I’ve used several times since.

Goals

Oathbreaker was written specifically to figure a few things out. As a foray into systemic design (of course), many of its more interactive elements worked better in digital form and were never included. But the playful ideas around changing reality and affecting things through the use of demonic powers were definitely included.

My design goals were:

- Figuring out who the player’s avatar is, what motivates them, and how they are connected to the world they live in. Empathetic role-play, considering what motivations the world provides based on the key “demon-powered” elements of the setting and making it plausible enough not to cause dissonance.

- What kinds of factions and different interests could exist in this world based on the player and how to generate conflict from the player’s goals. More narrative than empathetic, but one of the most effective parts of the tests when I look back at it today.

- Experimenting with missions, objectives, success, and failure. Mechanical role-play, as a way to figure out which kinds of missions felt more compelling than others, but also narrative role-play since it implied what kinds of story beats we’d be interested in pursuing if we took a more narrative direction with the game.

Some things were also actively avoided, since they didn’t really help the game’s design:

- Combat was largely ignored, because it would be designed in the first-person shooter in some detail and Oathbreaker couldn’t really solve any issues.

- Enemy design was also ignored, except as exploratory role-play to find inspiration on what kinds of opposition could be encountered in The City based on the factions involved.

Truth

Most of Oathbreaker is a conversation engine. We can set up some scenes and talk through how they play out. Because of this, it doesn’t use any authoritative truth but relies instead on procedural truth via random tables combined with situational truth and table consensus.

Cooperative Play

The digital game itself is cooperative, so it made sense to make Oathbreaker mostly cooperative too. We randomise things together, we create and discuss our characters together, and we generate and complete missions together. Each player does play a single selfish character, so sometimes they may not have enough reasons to cooperate, but then we can explain it using the goals and objectives. Discover more reasons for them to cooperate.

Sketch Maps

With an objectives-based game, it can help to think of a map as the sketch for a movie set. We don’t care so much about how it’s related to other sets, as long as it’s believable enough to work and has some measure of internal consistency. We should also have a good concept of how it looks like, as descriptive adjectives.

Role-playing games may refer to the areas on maps like this as “zones,” and the trick to making it interesting is to have enough of them.

In the below example, there’s just Mansion, Parking Lot, and Guard House. The mansion itself could just as easily have been subdivided into Kitchen, Atrium, Gym, Entrance Hall, and so on. How detailed we make it is up to us.

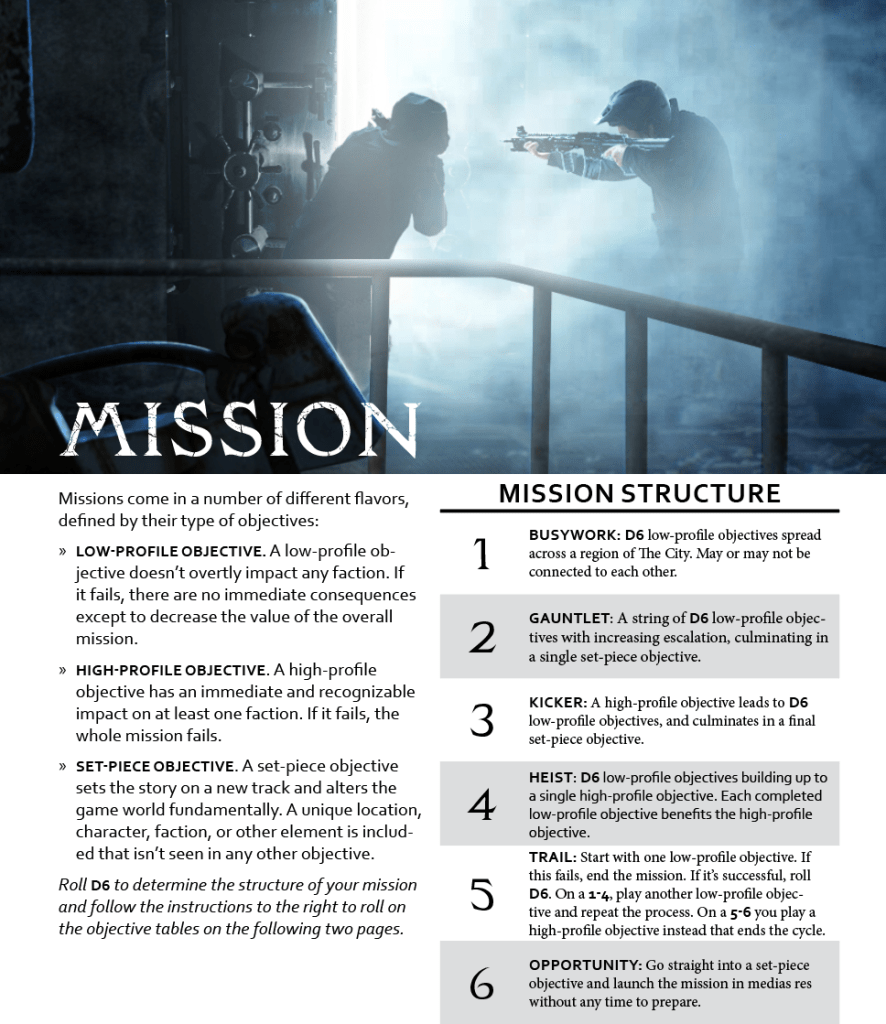

Mission Generator

The beating heart of Oathbreaker is a set of random tables that creates missions. It generates this in a number of steps.

First, a Goal is set, which gives you the reward you will be given if you complete the mission. You also figure out which Faction you are working for, and which faction you are working against.

Second, a very broad Location is determined. A Faction Claim, since it has to have ties to one of the power groups of the setting. It’s one of six districts of The City and provides some ideas on what you could find there.

Third, and illustrated in the screen grab below, you find out what the Mission Structure is, and then generate the objectives this requires.

Once all three steps have been completed, you have a mission to play.

Mechanics

For Oathbreaker, the focused mechanics approach fit quite well. It has mechanics for creating characters, playing objectives, changing reality, and making demonic pacts. No other mechanics are necessary.

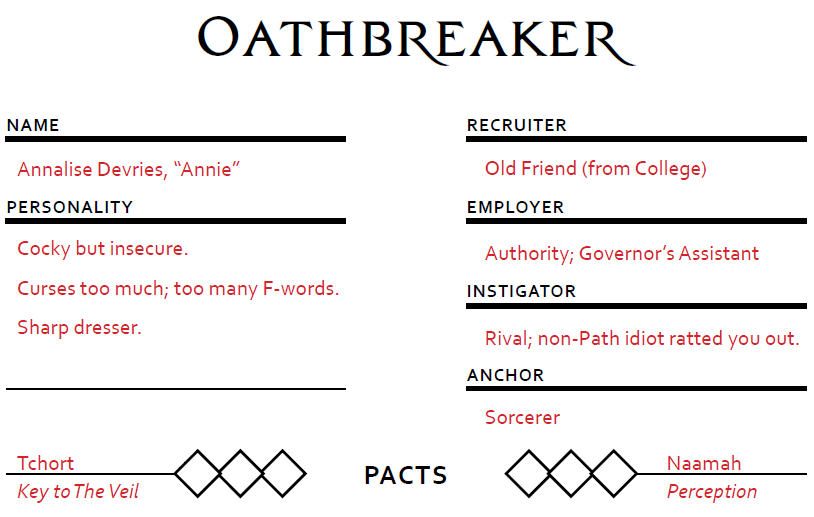

Character Creation

Each character is a selfish individual that managed to gain access to the Veiled Path but chose to break their oath and leave as an oathbreaker. When characters are created, each player rolls to find out first who recruited them, what they did for the Veiled Path, who made them leave, and who they tried to find after leaving.

Each of these tables only has six entries, so that it’s fairly likely that some characters will share one or more of these. The idea is then that they also know each other and that these connections can be good or bad. This is good grounding for empathetic role-play. Maybe the recruiter was my brother, but also your lover. Or we had the same employer inside the Veiled Path, but left for different reasons. This creates situations where we may not trust each other and where we will automatically start to dig deeper into the game’s world.

It’s also great grounds for quickly generating a number of faces that can represent characters we’d encounter in our world. If we missed something at this stage, it will usually be obvious.

Soul

Soul is measured in dice placed on your character sheet or on the notes representing specific threats at a location. There was never a hard rule for how many of these dice you would start with, or if you should start with any at all. If someone opposed you when you tried to use magick, you’d roll dice from your Soul.

Sometimes, only creatures or characters with ties to demons have Soul. At other times, everyone has Soul. It’s a simple dial to turn..

Path

There are two paths in magical tradition. The right- and left-hand paths. Simplified, the saying is that “the right hand giveth, and the left hand taketh away.” What you would see as black magic follows the left-hand path.

For this system, which was just a paragraph or two long, the taketh and giveth was used literally. With the right-hand path, you could give someone dice from your Soul; with the left-hand path you could take dice from someone else’s Soul.

This way, dice can also be rolled to oppose such an attempt, or to transform into resources, damage, or something else, either for yourself or someone else. It’s an extremely high level abstraction since it made it possible to not commit to anything in particular.

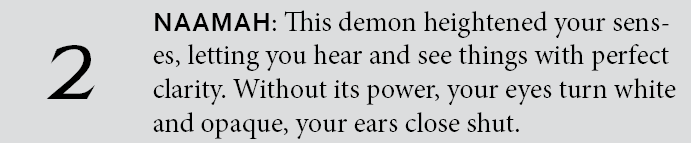

Pact

Pacts are measured in debts that must be paid off with Soul. If you look at the character sheet above, each of Annie’s two pacts (the one with Tchort and the one with Naamah) has three diamond boxes where none are checked. Each time the demon’s quite considerable power is activated, the player needs to either spend one Soul by discarding a die or check a single box that must then be paid off with Soul later. (The observant reader will also see that you can use the left-hand path to take Soul from someone else to pay this cost.)

There was never a hard rule for when a demon’s drawback would trigger, since that was part of what was being explored.

Using This Tool

As a final note, let’s go over how you can use this tool yourself. This is by no means a checklist of things you must do. In fact, you should only do exactly what’s needed for your specific project and nothing more.

Goals

If your game has empathetic, mechanical, situational, or narrative components, you may benefit from playing a role-playing game that explores it. But before you do, consider what you want to get out of it. Set up some concrete goals, like what was done for Oathbreaker.

Characters

Use the 5W+H questions, as many of them as needed, and look at them through the lens of the following.

- Theme. Start with a central theme stated as cleanly as possible. There are demons beyond the veil that are powerful enough to control reality.

- Agendas. Move on to the different agendas that the theme provides. Wanting to control the demons. Wanting to serve the demons. Wanting to hide the demons.

- Groups. Connect groups to the agendas, whether they are for, against, or neutral towards them. Law enforcement; those who want to hide the demons and maintain the status quo.

- Individuals. Populate the groups with individual characters. Emmet the Corrupt Cop, working for those who want to keep everyone in the dark.

Rules

You can skip this step entirely, or you can put extra effort into it at any level of detail that you want. One of my current spare time projects uses a fairly in-depth board game element to test full-scale combat, even though it won’t translate into its digital form. This has been written because I enjoyed it, an element that is certainly more important for hobby projects.

- Authority. Decide what kind of authority you want. The default tends to be a referee, but it’s not necessary, and for a more collaborative team of designers you shouldn’t have authority that is too centralised or bottlenecked to a single person.

- Mechanics. Use proxies, think about situations and abilities, and dig into what characters can and can’t do, as well as the role of luck in the mechanics. Randomisation can be important to a game in order to generate tension through uncertainty, but in role-play as a tool, it can actually distract you from the conversation. Only add randomisation, success, failure, and so on, if it’s important as a representation of what your game is about.

- Modularity. Since systemic design is my jam, and in many cases this benefits from a modular approach. If you can take any system and decide whether it’s active or not in a playthrough, this can help you zoom in or out as you need to. Oathbreaker does this in several ways, not least of all by making some of the concept’s core elements entirely narrative, such as the magick.

Play!

With just a page or two, maybe some dice, bring your team together and get to it. There’s no point to any of this if you don’t make use of it. Building a role-playing tool like this can definitely be an interesting intellectual exercise in itself, but the real magic won’t happen until you gather some other people around a table, friends or coworkers, and start exploring your game.