Around the age of 11-12, a game entered my frame of reference that quickly became synonymous to unplayable levels of complexity. That game was Advanced Squad Leader (ASL). The thick rules binder and giant Beyond Valor box that serves as the game’s starting point had just entered the collection of a good friend.

We played Warhammer Fantasy Battles at the time, and we played Middle-earth Role-Playing (MERP). Definitely complex games in their own right—more so for tweens—but ASL seemed several layers more complicated than anything we had ever seen before.

Sadly, we stayed away from ASL. It became a symbol more than a game. A symbol of incomprehensible levels of complexity that we could sometimes glance towards, but never actually tried to play.

More than two decades later, I’m having lunch with a colleague when ASL comes up in casual conversation once more. My jokes about it—still with the same focus on complexity as my 11-12-year-old mind—are immediately dismissed. After explaining some of the game’s strengths, it turns out this friend has an extra binder of rules lying around and offers me to buy it for cheap. Why not? It’s healthy to challenge your preconceptions once in a while.

Beginning to read it, I quickly realised I needed some modules to be able to play it. After buying those modules, and a couple of simplified starter kits, I finally got to play ASL, after picturing it as the staggering peak of complexity for so many years, and I loved it.

As a story engine, it’s amazing. Particularly its turn structure, where the defending player will be the one taking most shots while the attacking player holds their breath and moves ahead one terrifying hex at a time. It mimics the style of cover-based combat that you imagine from something like Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, and generates a turn structure that is much more interactive even than many modern wargames.

It is definitely complex, mechanically inconsistent, and has many of the issues ascribed to it, but more because of a decades-long expansion parade and a change in gamer preferences than because it’s a “bad” game in any sense. Our preferences as consumers have changed, same as we may find an episode of MacGyver slow and dull compared to when we watched it in the ’80s.

This introduction to wargaming made me curious to see what other gems could be hidden in the storied past of game design. I wanted to find out if my spontaneous longtime reduction of ASL into its complexity had made me miss other amazing game experiences I could’ve had with a more open mind. Maybe putting forward ASL as a kind of craft canon that game design students should play just like a movie student sits through Nosferatu still to this day.

I set off to find out.

Game Design

A caveat. The following sections deal with the game industry and how you can look at game design in a number of different arbitrarily delineated eras. Though I’ve done quite a lot of research, this is not an academic treatment of the subject. I am likely to get things wrong. Particularly since I’m generalising whole decades into just a few key takeaways.

There are ways that the eras differ significantly and that should inspire you to try a few games from each era even if just for the perspective it provides. But this is cherry-picked based on my personal interests and values.

Think of this as a conversation piece more than an accurate historical treatise.

Ancient Times

It’s incredibly hard for us to know exactly what kind of cultural context games had when we get really far back into history, and it’s even harder to dive into the methods and motivations of ancient game designers.

Games like the Royal Game of Ur, Go, and Chess, have varied cultural contexts, some even forming living history. Decks of cards and rolling dice are also prevalent and random chance is often given mystical properties.

But there’s not much we can say about the design of games in our past, except that it seems we’ve always strived to entertain ourselves with pastimes that trigger the imagination and that we’ve always enjoyed gambling.

Many of the interfaces established in ancient times are of course used still to this day. Like dice and cards.

Games You Can Try

- Royal Game of Ur. A mesopotamian game that’s around 5,000 years old.

- Go. A Chinese game that’s regarded as the oldest game still being actively played. Invented around 2,500 years ago.

- Snakes and Ladders. An Indian game that’s around 2,000 years old.

- Chess. The classic game that’s allegedly only played by smart people. (I wouldn’t know.) Probably 1,000-1,500 years old if you include its predecessors.

Kriegsspiel Era (1800s)

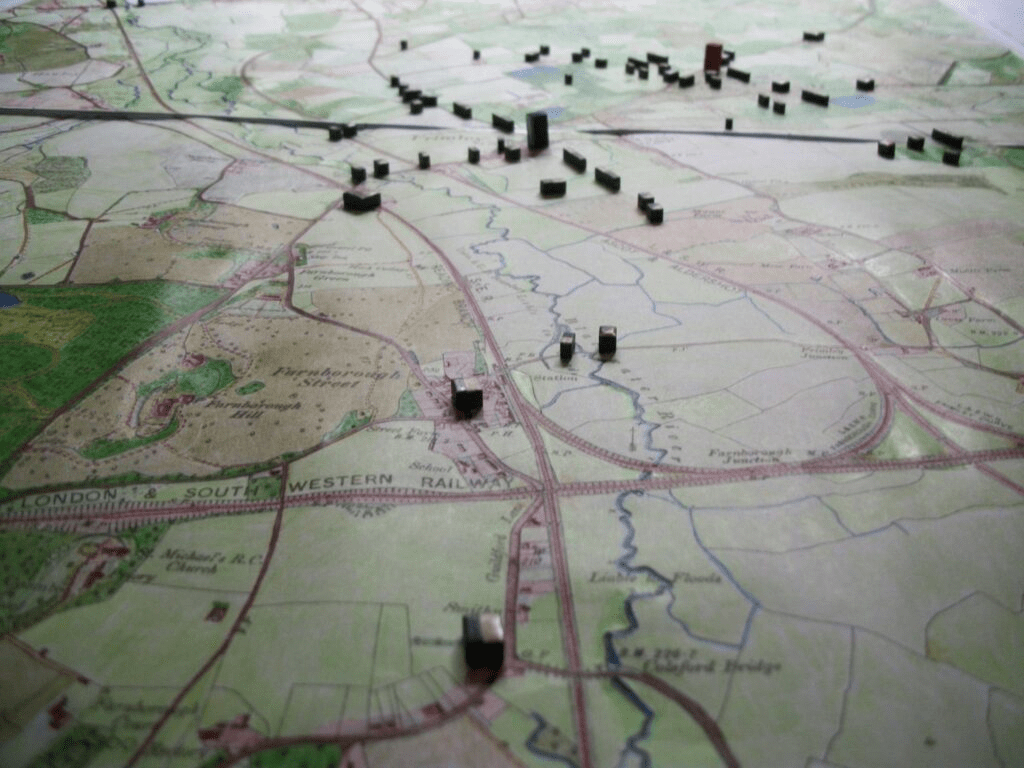

What is known as Kriegsspiel today starts with the detailed rules of Georg von Reisswitz, a Prussian army officer who is often regarded as the father of wargaming in its many modern forms. His actual father created the original game, but never finished it, and Reisswitz Jr. made it his own. He went on to arranging regular sessions with officers and setting up a workshop where he could produce more copies of the meticulously hand-crafted game.

Kriegsspiel was used among Prussian and foreign military officers as a means to educate them in strategic thinking. This distinction with Kriegsspiel as something practical and tangible and not just a toy is relevant and made clear by the suggestion that players do not read the rules, as this risks pushing them into a more gamey mindset. Rather, the rules are the domain of referees (called “umpires”), and players make decisions as if they are in command of forces on a field of battle. Their orders are received by the umpires, who report back what the outcomes of those orders are after going through them on a map or coming up with reasonable resolutions on their own.

This type of wargame is played by modern militaries still to this day, albeit often in digital form, and some of the decades we’ll go through have seen tight collaboration between gaming and the militaries of the world.

Games You Can Try

- Kriegsspiel. People still play this game, and you can most likely find a group or convention where you can try it out. Just don’t read the rules!

Pre-Wargaming Era (50s)

Games other than gambling games are principally for children in the early parts of the 1900s. This makes them an effective learning tool, which is what gives us Lizzie Magie’s The Landlord’s Game (1904) and its lessons on capitalism, that are then somewhat ironically turned into Monopoly (1935). This era also gives us Diplomacy (1958), one of the greatest games ever designed, and its focus on player trust as an expendable resource. A conscious design that eliminates dice rolls in favor of player unpredictability. This is games as something that can make a point.

In the same vein, we also get a long line of propaganda games. Games targeting children with the messaging of the various undemocratic regimes of their respective times.

Game design taking its first tentative steps into, but still mostly as toys. But when you think of a design paradigm to take with you, think of theme and how much it matters.

Games You Can Try

- Monopoly. The most sold board game of all time and one you have probably played already.

- Risk. Another iconic game that many non-gamers will play at some point under the pretence of family entertainment. Its approach to dice rolls have inspired many other games.

- Diplomacy. Remains in print to this day, with a new edition recently released by Hasbro.

Early Wargaming Era (60s)

With play-by-mail and games organised through magazines, game design finds its way into the adult consciousness in a bigger way. While the big mainstream game productions are still mostly toys, a big deal in this era is also simulation. Many of the people who engage in gaming are academics, and games often reflect the same political turmoil and leanings as the universities of their time. Not to mention intellectual historical reenactment, like attempting to end World War II earlier, or seeing the effects of different strategies.

We can find protests against the war in Vietnam in game form, same as we can find games simulating infantry engagements in the same conflict. As I mentioned in my previous post on platforms, tables, charts, forms, and so many other bureaucratic artifacts of the time enter gaming and are here to stay.

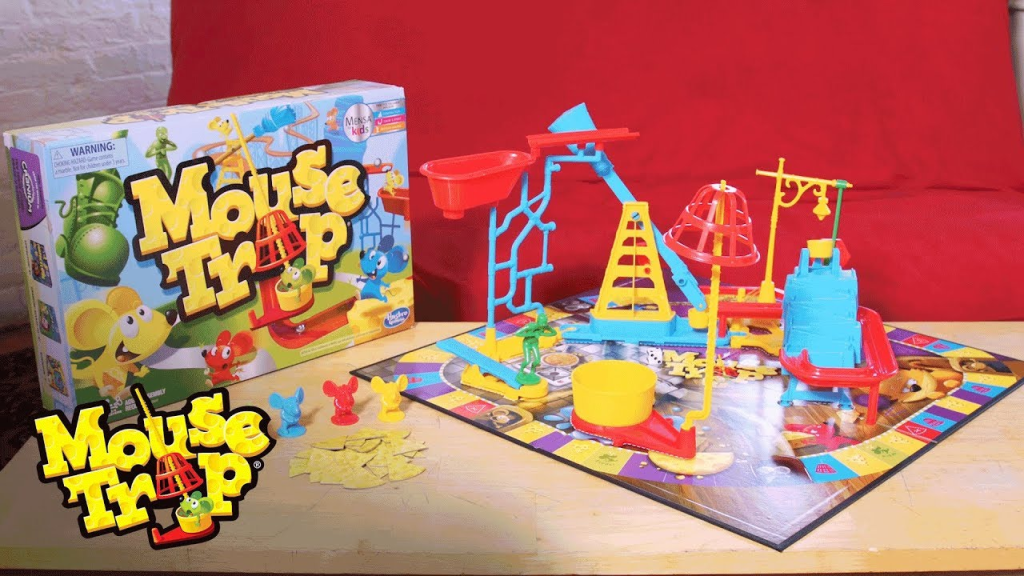

To take something with you from 1960s game design, think of invention (like with Mouse Trap and Operation), but also think of advertising.

Games You Can Try

- Mouse Trap. A game that still remains in print and has presumably entertained kids of many generations. Definitely more toy than game.

- Operation. Also a toy game and one that’s been with us since its invention in the 60s.

- Acquire. Another game that still remains in print and which’s representation of commerce and trade still makes for a compelling gameplay experience.

Wargaming Era (70s)

Some of the big games in wargaming are released in the 1960s, including Afrika Korps and Stalingrad. You must remember that the 60s and 70s are in fact closer to the end of the second world war than to today. But this obsession with depicting battles for or against nazis lasts to this day. Maybe because it’s simultaneously safely distant from the present day but at the same time similar enough to feel compelling for our modern sensibilities.

Out of wargaming culture comes Dungeons & Dragons, partly with wargamers taking inspiration from the Kriegsspiel of old and expanding the role of the referee into the Dungeon Master. Gary Gygax sells his iconic game from his garage, moving 1,000 copies in its first year, climbing to 3,000 copies the year after. It will go on to sell many many more copies in the years to come, reaching millions of books per edition in our time. Meanwhile, analog games are selling tens of thousands of units in the 1970s, with Panzer Blitz and Squad Leader each moving as many as 200,000 copies in the 70s alone. The Game Designer’s Guild is created in this era, supporting the sentiment that wargaming may actually become a way to earn a comfortable living. (A dream that would shattered in less than a decade.)

Game design in the 1970s is incredibly diverse. The idea of design for effect comes from this era. An idea that a mechanic itself doesn’t have to be realistic or simulational, but can still achieve the same effect when you look at a game turn as a unit of time rather than having every single interaction represent something in the simulation. This is the paradigm behind successes like Squad Leader, and remains deeply embedded in game design.

Something that’s also very popular in the 1970s is the idea of programmed instructions, where you will play one scenario at a time and gradually introduce the rules you need to play. Once you’ve finished all of the programmed instructions you can replay the scenarios or play more full-fledged scenarios knowing the whole ruleset. This feels like a foreshadowing of modern tutorials, but are frankly often better than modern tutorials.

One of the principles that seem lost to time from the 70s is that imagination is still central. Many of the situations caused by dice and rules interacting are left vague or extreme, because it gives you something to talk about. Something to make your own. Early tabletop role-playing games don’t have hundreds of pages of lore text and rule exceptions; they provide blanks for your own imagination to fill in. Wargaming is the same, and a lot of the associations you can get from having a squad leader’s modifier be +1 rather than -1 builds a strong narrative without any need for exposition.

Games You Can Try

- Dungeons & Dragons. Just make sure to try a version of the original from 1974 for purpose of the points being made.

- Squad Leader. The game that precedes the game that made me write this long-winded rant. Still a great game and Advanced Squad Leader still remains in print under the Multi-man Publishing umbrella.

- Dune. Demonstrates an early version of the much more thematic games to come and how gaming will make a solid pivot away from historical simulation and towards more fantastical and brand-aware pastures. Once again in print since 2016.

- Pong. Allan Alcorn’s iconic game, adapted by Atari as arcade cabinets and even home consoles, and can still be enjoyed today.

Explorative Era (80s)

I’m not old enough to have a deeper understanding of gaming or game development in the 80s and earlier. But one thing is quite clear from listening to interviews and reading about it: teams were usually tiny. Often, you’d have just one programmer who would put the functionality, art, sound, and everything else together. Sometimes on graph paper that had to be mapped to Assembly instructions; at other times with custom tools made for one particular game. Then some other person or group of people would play what they just put together and issue feedback that could be acted on directly. Not as some official QA process necessarily. It could just be someone at the office who swung by or had a floppy waiting on their desk in the early morning.

That you had to make many things from scratch, even rewriting hardware instructions for each target platform, meant that there was a lot of playing it safe. A company that made a successful flight simulator kept on making flight simulators, for example, because the lure of a predictable income is usually more interesting than gambles that may simply lose your investment. That’s right, a precursor to the “games are so expensive to make” nonsense. (A line that returns in every decade, it seems, and somehow always motivates worse conditions for gamers and game developers.)

But with such small teams, there was also a lot of room for experimentation, since it’s much cheaper to experiment when you’re paying a single salary versus the salaries of a whole team.

Game companies like Bullfrog, Microprose, SSI, etc., are successfully making and selling digital games. Atari, Nintendo, Sinclair, Sega, and others, are selling home entertainment systems—game consoles—while shifting millions of copies of popular games. The big names of the previous few decades, with SPI, Avalon Hill, TSR, and so on, are still selling board games as well. It’s something of a golden age of game design. A time where people who used to do analog games move into the potentially more lucrative digital space but can safely maintain a foothold in both.

The landscape will change during the 80s, with the rapid increases in power of computers. More memory, more colors, more CPU cycles. By the end of the 80s, more studios are writing object-oriented code, building code libraries that can be shared between projects, and growing their team sizes.

Whole genres, like adventure games, are popularised and see rapid growth in this era, with Roberta Williams becoming a household name for fans of her King’s Quest games, and Ron Gilbert with his The Secret of Monkey Island.

One part of game design in this era is evident in the tabletop role-playing game space, and it’s what can be referred to as the “commodification of imagination,” as expressed by the Hexjunkie blog:

“[Gary Gygax] realises that if D&D remains in it’s current collaborative form it’s almost impossible to make money from it. You can sell someone a rulebook and then they do everything else. Maybe you sell some miniatures but the game doesn’t require many of them if any at all.”

From “The Commofidication of Imagination,” on the sadly defunct Hexjunkie.com blog.

Pushing people towards official modules and having to make additional purchases is what this refers to. You can no longer just roll some dice and make up your own reality; you have to use the official reality as released by the developer, combined with the official miniatures.

This early stumbling block on the road to monetisation will follow us throughout gaming. With game designers often less interested in money and business people less interested in game design, the clash between freeform creativity and the sale of content is something we still haven’t figured out.

In game design for this era, there’s a lot of randomisation, used to create effects that tell interesting stories. Many games rely on player elimination or losing your turn, and they are not afraid to waste your time or put you into a spot with no way of winning if you make the wrong decisions. What we may talk about as hardcore games today seem like easy mode compared to the hardcore games of the 80s.

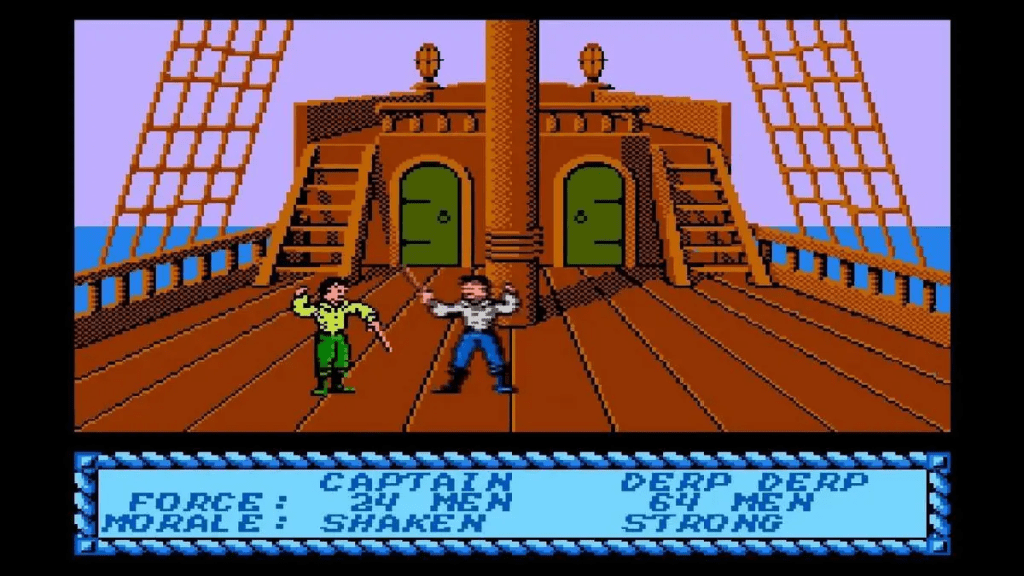

We see some games introducing minigames as components of larger metagames, as with Sid Meier’s Pirates, and we also see Shigeru Miyamoto bring Kishōtenketsu with him into game design and establishing ways to use its turning point structure in game design. Probably one reason we still have things come in threes.

Games You Can Try

- The Hobbit. A text adventure with a simulated world, that was innovative then and remains innovative to this day. Part of a text adventure parser trend lasting into the 80s from the 70s.

- Super Mario Bros. The original goomba-stomping sim. A game that can still teach elements of game design to modern designers, maybe most importantly in how it communicates its most important concepts. If you don’t jump on that first screen, it’s simply game over.

- Warhammer 40,000. Miniatures gaming was popular before Games Workshop turned it into the franchised billion-dollar industry of today, with the first edition of Warhammer Fantasy Battles in 1983, with Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader following in 1987. Both are still played worldwide.

- The Secret of Monkey Island. Released in 1990, but gets to represent the living legacy of the adventure game.

- Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game. Recently released in a 30th anniversary edition, it serves as an excellent example of a game that exists at the border between imagination and commodification. A game that simultaneously invites you to experience a Star Wars story through play, but also tells you to go out and buy official adventures.

- Street Fighter. Hadouken! No idea what it means, or even if it means anything, but that aurally pixelated vocalisation is ingrained into my skull forever.

- Sim City. This is an incredible game and in many ways brings toys back to gaming but in digital form.

Entertainment Era (90s)

Personally, I think this next era is to blame for the type of hustle mentality we still see among game developers. We should remember that when Romero, Carmack, and the rest of id Software (and others) worked insane hours of overtime, they did so for projects they owned—they didn’t do it solely for external shareholders. “Crunch” has since become the industry’s pet name for unpaid overtime. But if you’re an employee, you don’t get the benefits of that unpaid overtime like Romero and Carmack did.

This era is important for gaming and game design. Digital games start outselling analog games and many of the wargame companies that were hopeful that they’d get to make a decent living disappear in bankruptcies or mergers. Some of their most influential designers move on to digital games, but there’s also a great loss of game design talent that simply drops out of game development entirely.

With the rise of the home computer, many more people gain access to games. Games enter the big leagues. Railroad Tycoon sells 400,000 units. Wolfenstein 3D sells 250,000 units. Doom and Doom II together sell just under 3,000,000 units and usher in a new age of shareware and Internet sharing, but also of software piracy.

Game design is still usually shared across developers with other skills. Programmers and artists, most prominently. Hollywood also gets its eye on gaming again, particularly with the CD-ROM and the concept of full-motion video letting them put famous actors on box covers. Oh, and they get to complain that games are so very expensive to make, again.

With teams of IT-savvy developers, libraries of shared code turn into the first game engines that are also licensed to other companies in first- and third-party deals. This gives us games as diverse as Heretic and Redneck Rampage. We also start seeing gradually more widespread use of dedicated game hardware like sound and graphics cards.

Many of the most iconic of all action games ever made are released in this era, with titles like Doom, Quake, Diablo, and Half-Life establishing design paradigms that many of us still ape to this day. Things like abstract level design, where the design, according to John Romero, “has a beginning and an end, but many ways through, and it’s not so much a linear experience as a continuous one, where players come to know the space as they might know a person and decide to explore and challenge it as it reveals itself to them.” Not realistic or attempting to mimic something from real life; just serving the game it’s designed for and focusing on the action.

Under the shadow of the action games, but still successful in their own right, we also see development of more systemic titles. Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss, Thief: The Dark Project, System Shock 2, and their kind. The games that still motivate me to do what I do and that I’ve written about before.

Games You Can Try

- Doom. An iconic and important title which’s value can hardly be overstated. Where many would hold Quake as more important, I think Doom is the better game.

- Magic: The Gathering. The game that created the collectible card game trend, and a game that’s a big deal still to this day and should be mandatory for game designers to have tried at some point.

- Myst. A pivotal adventure game that probably spawned the still popular hidden object genre.

- Witchaven. First of the Build-engine games, which would later be the engine of choice for Duke Nukem 3D and many other games.

- StarCraft. A game that will be an important step on the esports ladder and that remains both a singleplayer story that is remarkably well told and a fast-paced strategy sport that’s not for the faint of heart.

- Civilization. An important turn-based strategy game series which’s sequels continue into our present day and remains an engaging game that has made generations of gamers say “just one more turn.”

- Metal Gear Solid. A game that turned many things upside down and played both with the game as a form of media and with what it could achieve. Also a game that shows the incredible value of game design and out-of-the-box thinking as a craft.

- The Settlers of Catan. Starts many new trends in board gaming and puts board games on the radar for generations who had limited previous interest.

- Deer Hunter. A surprise hit and a game that introduced publishers to the casual games market and budget games distributed through channels like WalMart in the U.S.

Third-Party Era (2000s)

With greater success comes more investment money and the number of video game publishers trying for a piece of the pie skyrockets. Many try to capitalize on trends, with first-person shooters (FPS) and eventually massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) becoming the hot topics of their respective times. As a developer, with boxed copies and retail still dominating, you can’t get your game out into the wild without a publisher, further cementing the publisher as the key enabler in the industry.

This is an era where console sales usually trumps computer game sales many times over. One classic example is how Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare allegedly pushed some 13 million units on consoles, but a measly 400,000 on PC. Numbers that you will recognise as very big numbers by the standards of the past few decades, but that are now changing priorities in shareholder meetings.

Game design has now become its own thing, and in some areas designers are known to their communities by name. Cliff Bleszinski’s credit as the level designer for maps in Unreal Tournament makes him a household name in some circles, and independent developers like Petri Purho (Crayon Physics), Jonathan Blow (Braid), and Phil Fish (Fez) achieve both success and sometimes notoriety. It’s clearly possible to make it without the support of the previously mentioned publishers; something that brings more hopeful young developers to the industry.

Big digital games can now sell 5-15 million copies, while the wargames of the 70s and 80s and many of the genres of the 90s have been largely forgotten. Though Ron Gilbert stated in an interview that adventure games probably sold just as much or more in this era as they did in their heyday; it was just not enough sales to catch mainstream attention anymore. In other words, no, adventure games were never “dead.”

Third-party developers are common, often with advance against royalties contracts, that makes it so developers never make any money from selling games but from making them, and are often hiring and letting people go in a cyclic manner tied to the start and end of their projects. As Chris Taylor of since-merged Gas Powered Games put it, a “500% loan.” An unsustainable type of business that capitalizes deeply on the passion of the young hopeful developers entering the industry at this time and inheriting the hustle culture previously mentioned. (Present company included.)

Game design in this era is quite experimental and cross-platform, with Halo: Combat Evolved and its spiritual predecessors (in Golden Eye and Perfect Dark) leading the way for a whole generation of gamers playing first-person shooters on consoles. With Nintendo’s Wii console, we get more spatial experimentation, and gaming spreads even more. Not to mention the two most sold gaming consoles of all time: the PlayStation 2 and Nintendo DS.

Games can be art, games can be anything, and game designers are the ones making it happen.

Games You Can Try

- Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare. This game set a new standard in more ways than one. Not least of all its 60 FPS target on consoles.

- Canabalt. Harkening back to a time when Flash games could be shared as a link to anyone you knew, and also foreshadowing many of the endless runners to come.

- World of Warcraft. This game’s popularity pushes into the mainstream, practically becoming its own subculture. It is also a precursor to the platform games of today and starts a decades-long struggle by competitors to make a “WoW-killer” that has never materialised.

- Half-Life 2. An important game in many ways, not least of all for its atmosphere and world building. A game that some still hold as the peak of the singleplayer first-person shooter genre.

- The Sims. After suffering internally, this social simulator is launched to become one of the most sold games of all time, and it still has an active community of players.

- Shadow of the Colossus. One of the more experimental games originally released on the PlayStation 2, during a time when a debate around whether games can be art was somehow a thing.

- Angry Birds. Allegedly the 50th or 51st game thar Rovio released on the AppStore, and a game that was part of the original run of highly successful mobile games.

Cinematic Era (2010s)

Games continue to grow, with a year-over-year expansion that’s unprecedented in entertainment. The democratisation of game engines like Game Maker, Unreal Engine, and Unity, as well as increased exposure and a much lower barrier to entry, particularly on mobile platforms, leads to a second and much larger wave of indie developers that has kept growing ever since. Game development is taught at schools across the globe and game designer seems to be the vaunted title on everyone’s mind.

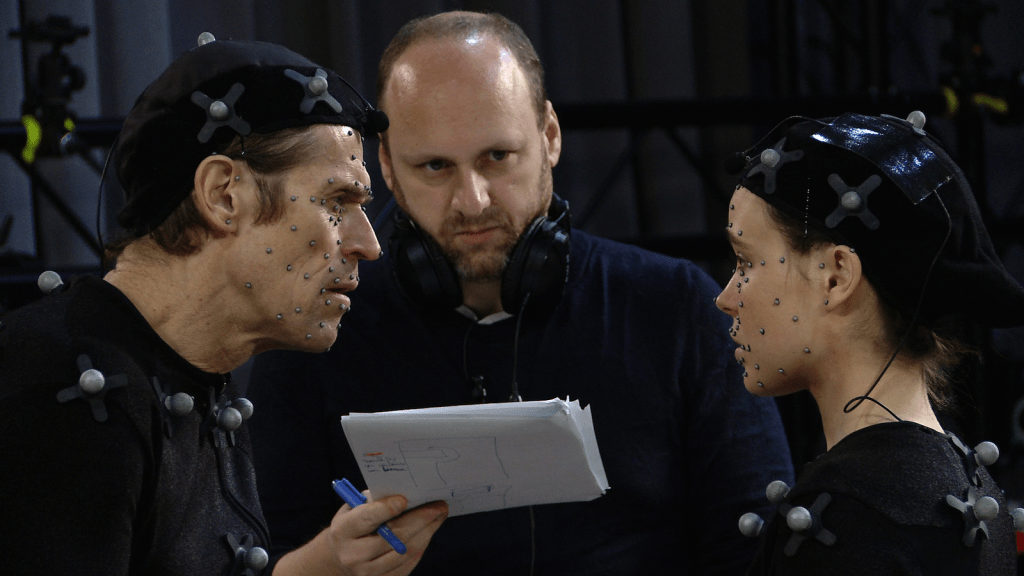

More than anything, the cinematic era is when games become obsessed with Hollywood. Auteur directors like Hideo Kojima, David Cage, Cory Barlog, and Neil Druckmann, actively turn their games into feature films. Studio teams balloon to thousands of people and are increasingly first-party. Successful titles sell tens of millions of copies, but the publisher power balance is somewhat disrupted, with independent companies like Mojang (Minecraft) sometimes making the bigger splash.

Game designer is now a job with many different specialisations. You can work as a monetisation designer, a system designer, a combat designer, mission designer, and much more. But those titles rarely mean the same thing at two companies at the same time. The booming Asian market for video games overtakes the market in the west, and as in previous eras, the only thing that stays the same is the rapid rate of change.

Games You Can Try

- The Last of Us. A game that shows the dominant traits of many highly praised games of this decade, and one that’s since been turned into a television series.

- Gone Home. Released the same year as The Last of Us, and set something of a trend within the ‘walking simulator’ subgenre of games.

- Candy Crush Saga. Another game that can serve as a prediction of what is to come. Some estimates claim that half of the world’s connected population has played Candy Crush at some point.

- Pokémon Go. The game that made many a pale sun-averse person go outside to train their pocket monsters, and transcended age as well as culture. A phenomenon as much as it is a game.

- League of Legends. A big hit and even bigger earner, with a dedicated esports scene and countless fans. Boasts an insane 117 million active monthly user average.

- Apocalypse World. A game that is often held as an example of a new direction for independent tabletop role-playing games. Both in its rules and play style, and in its writing.

Platform Era (2020s)

Traditional publishers are laying off staff in droves and the circus of mergers and acquisitions has spiralled out of control. Two things are true about the games industry in our current era: business and development have become two separate things; and game design as a craft is in a better place than ever before. The biggest projects are larger than ever and the smallest are more similar to the one-man development teams of the early decades.

Monetization, analytics, user experience, games as a service, gamification: game design is more important than ever and a highly diverse field that has matured in some ways but stagnated in others. Board games are immensely popular again. Digital games are larger than ever and played by a wider audience than ever.

What’s impressive with our time right now is that the smallest niche can become a successful business. There are studios making horror games, role-playing games, digital board games, and everything else you can imagine, and they can all make a decent living or more.

The biggest actors are making more money and selling more copies than ever before. But you don’t need to be big to be successful.

We would finally need a Game Designer’s Guild!

Games You Can Try

- Roblox. This isn’t a “game” as most of us old people would have it, but a great example of what the platform era has led to. Millions of user-generated experiences can be switched between at the flip of your finger, while keeping you inside the Roblox ecosystem. It was released in 2006, but its impact on the gaming ecosystem is coming into its own now.

- Genshin Impact. Demonstrates that games as platforms don’t have to look a certain way and are not required to have multiplayer components. Play it just to experience how different it is from most of the games we play today.

- The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom. The second of two modern Zelda games exploring systemic design in a big way. An amazing game that manages to both carry the legacy of its namesake and do something new at the same time.

- Baldur’s Gate III. This is my tongue in cheek addition to the conversation, because I want BG3 to predict what is to come: an era of systemic games sold as whole experiences. I don’t think this is what we will get, but a man can dream.

- Roll20. Not a game but a platform for playing tabletop role-playing games online. A platform that sees a high volume of users and has become a huge way to engage with what used to be caricatured as a basement-dwelling hobby.

Takeaways

Every era of game design has had a lot to offer. But because game designers don’t engage with the history of the craft to the same extent as the movie students who watch Nosferatu, this tends to be forgotten. Instead, game design is often cyclic. Innovations like programmed instructions, design for effect, or even the brilliant minigame structure of Sid Meier’s Pirates, are forgotten or reinvented.

When the first edition of Twilight Imperium came out, its designer felt that modular hexagonal boards was something new—something innovative. That no one had done it before and now suddenly both his game and the game Settlers of Catan were doing it at the same time.

But those modular boards had been a thing nearly 20 years earlier, in the game Magic Realm, from Avalon Hill. One of the lost design treasures that highlights the point I’m trying to make: that game design is cyclic, because new generations don’t play the games of the older generations or may even consider those games something lesser than the new. Just like I did when I dismissed Advanced Squad Leader for its complexity, without actually knowing.

If you want to well and truly immerse yourself in the craft of game design, you should play more games from more eras. You should understand what each era brings to the table (sometimes literally) and you should let your curiosity stave off the spontaneous reluctance whenever there’s mathematics, hexagons, or combat resolution tables involved.

Every era of game design offers insights about our craft. Every era carries secrets and design tricks with it that are worth taking inspiration from. Those may or may not be the same inspirations as I’ve personally found—but they’re there for you to discover.

When you do, come back here and tell me what you find!

4 thoughts on “Eras of Game Design”