This is an unplanned Part 3 in my series on gamification and goes into loot. Itemised rewards. Maybe the most compelling of all reward systems that games have yet to use, so it’s possible that it was simply too obvious to be included the first time around.

Designing a reward system is a ton of fun, but not easy. Particularly since players will often chew through what they’re offered much faster than our predictions say.

Here I’m hoping to provide you with the pieces you can use to make your own.

Loot

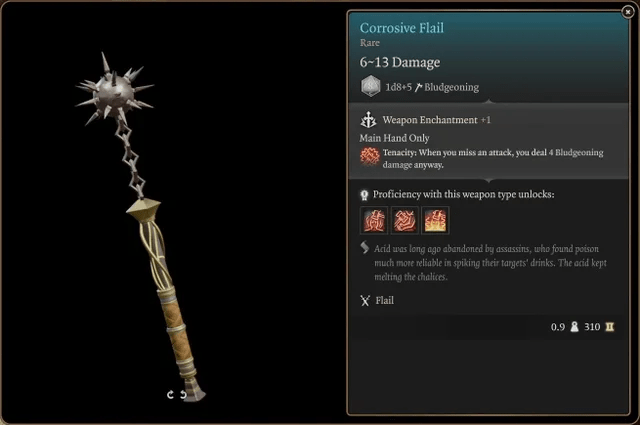

Whether you look at Wizardry, or any other early game with items in them, inspiration was often taken directly from the first few editions of Dungeons & Dragons. These set a standard of common items with simple numeric differences, like the amount of damage dealt, paired with magical items that provide bonuses on top of these differences or introduce unique features.

Many of the staples of OD&D are still common. Including the +X modifiers to weapons and armor, the Bag of Holding, and so on. Items players have looted from the pockets and treasure troves of dead monsters since 1974.

This is ostensibly where the word “loot” comes from, as well. You killed the kobold and then looted its corpse. It’s not a great word from an ethical perspective, but neither is murder, so we’ll let that slide for now. Some words in gaming lingo are simply here to stay.

Operant Conditioning

We can’t talk about loot without mentioning B.F. Skinner’s experiments and what many refer to as the “Skinner box.” This box is actually a complex contraption with multiple options. It can have levers, buttons, blinking lights, electrified surfaces; all of them intended to test various ways to see how animals like rats and pigeons react to various types of stimuli.

One interesting thing with this box is that it has demonstrated the addictive qualities of random rewards. The so-called variable ratio reinforcement schedule is a type of operant conditioning where random rewards creates an incentive to keep playing, because just one more pull may give you a reward.

This is far from the only thing Skinner demonstrated using his box, but it’s the one thing that video game designers tend to focus on, and also in many ways the most problematic one.

Gambling

We also can’t talk about loot without mentioning its relationship to the design of gambling games. Slot machines, one-armed bandits; you know of them even if you don’t know them. Gambling games are built to make money for the casino that hosts them. The “house.”

Out of all the money put into something like a slot machine, around 5% is kept by the house. This means the Return To Player (RTP) is 95% of the money spent. Winning has the interesting effect on human psychology that we think we’re “lucky,” or maybe even on a “winning streak.” But you’re only getting 95% back over time—so that psychology will push you into losing 5% over and over until you run out of money. You can definitely make money gambling, but it requires you to go against the impulse to keep going when you’re doing well. It goes against your operant conditioning.

For video games, this same dynamic is not always tied to monetary value, since many countries have special regulations around gambling, but is instead tied to your time. You will play the game hoping for some specific reward popping out of the variable ratio schedule, but you will ultimately only get 95% of your time’s worth. Never quite what you hoped for. Why? Because “just one more game” or “just one more dungeon” is what the design is there to make you feel.

What to Award

Most of us probably think of items, like guns or armor or potions, when we think of loot. But when you work with a reward system it helps to think less of the visual representation and consider what you are providing the player with instead.

Progress

Gamification thrives on progression systems. Nothing new there. This means the cheapest reward we can give our players is some more points towards one of their several progress bars. It can also be unlocks of additional world areas, more rewarding variable schedules, or something else.

You typically want to have at least three levels of progress going: one tied to your second-to-second micro progression, another to your minute-to-minute macro progression, and a third to the hour-to-hour meta progression.

That way, the player always has something that’s close to unlocking. Not only to keep them playing but also to make them come back after ending the play session.

Biscuits

Some games have collectables or other types of “biscuits” that you can pick up that don’t really provide any value except for completionists. It can be fun to discover them but they won’t give you anything substantial beyond the brief satisfaction of finding them. Many games will pad their reward systems with biscuits as foiling for more substantial rewards.

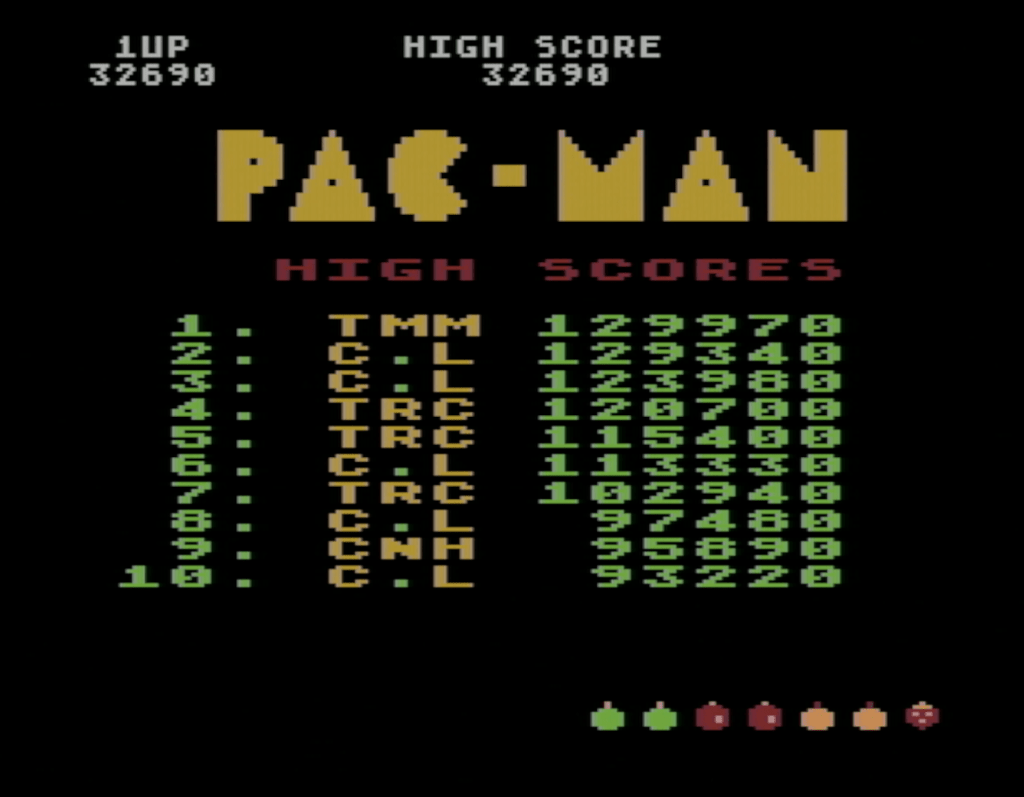

Score

One type of reward that can feed into external systems is point scores. It can be competitive, for example as a high score system, or it can be entirely for your own benefit. It doesn’t have any impact on the game itself, which makes score a fairly cheap type of reward. The trickiest thing is to balance the scoring itself so that it feels rewarding and isn’t just an abstract layer of numbers on top of everything else.

Currency

Currency that has no tie to real-world money is usually referred to as virtual currency or soft currency. This is your gold and silver coins that are part of the game’s closed economy and usually balanced so that it follows the general progression curve of the rest of the game. In other words, buying the most expensive items will happen in the later stages of the game.

Many modern service games also have a premium currency or hard currency, which is tied to real money. Not all games hand these out as rewards and games that do usually hand them out in tiny amounts that won’t let players purchase anything but are designed to incentivise players to buy more.

Modifiers

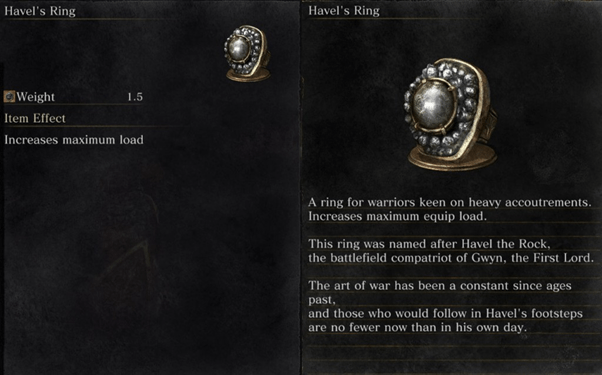

In a system with balanced mathematics, you usually have several different layers of numbers. First, you have your baseline number which you can use for balancing purposes. Then you have the attributes applied to something like a character class or enemy. Thirdly, and what is usually represented by items in a loot system, you have your modifiers.

A modifier is something that gives you an extra boost in a specific area. Say, lots of fire damage, or an increased chance of finding more virtual currency. These items can become very attractive for players wanting to maximise the efficiency of a specific build. Maybe their gold farming build in the case of the additional virtual currency example.

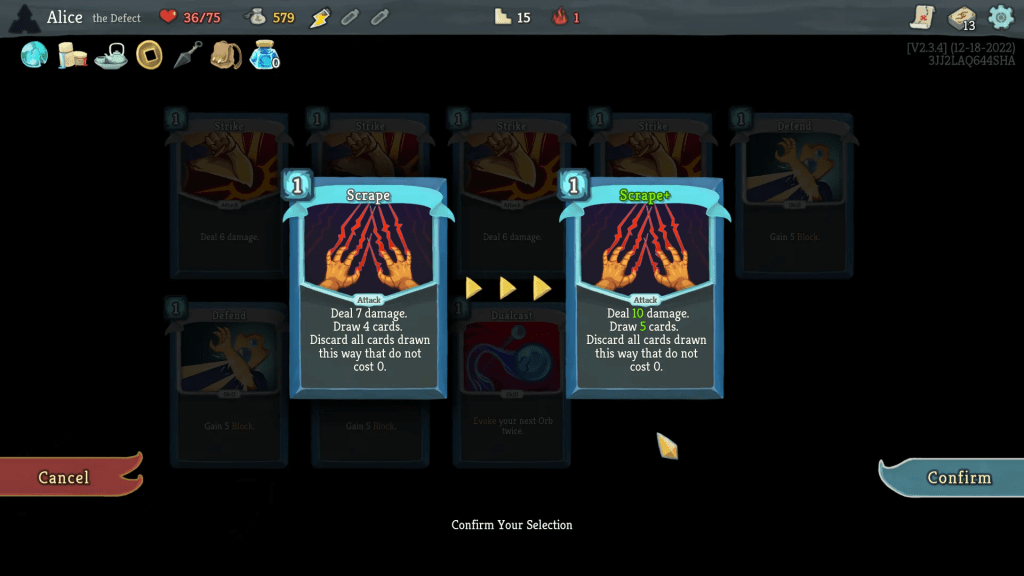

Features

Beyond having only the numeric differences of a modifier, rewards can also provide unique features. Many games that have this type of reward will reserve it for their highest reward tiers. It’s also often combined with other rewards, but we’ll come back to the concept of combination later.

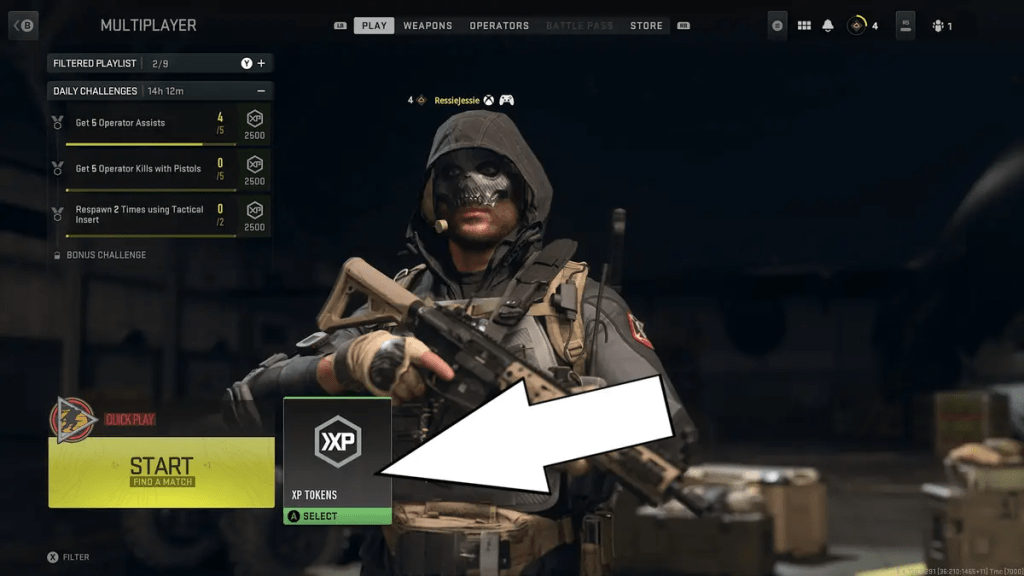

Boosters

A booster is something that provides a considerable advantage to something else, usually on a limited timer. The traditional form is the video game powerup—think of quad damage in Quake that makes you deal four times as much damage for 30 seconds—but modern service games often tie it more strictly to progression.

Double XP for 24 hours. Increased drop rates for one hour. An extra 25% experience from kills for two minutes. Since they are limited, they represent a type of reward that can be handed out in identical form more than once and is therefore good from a development standpoint. Make once—use forever.

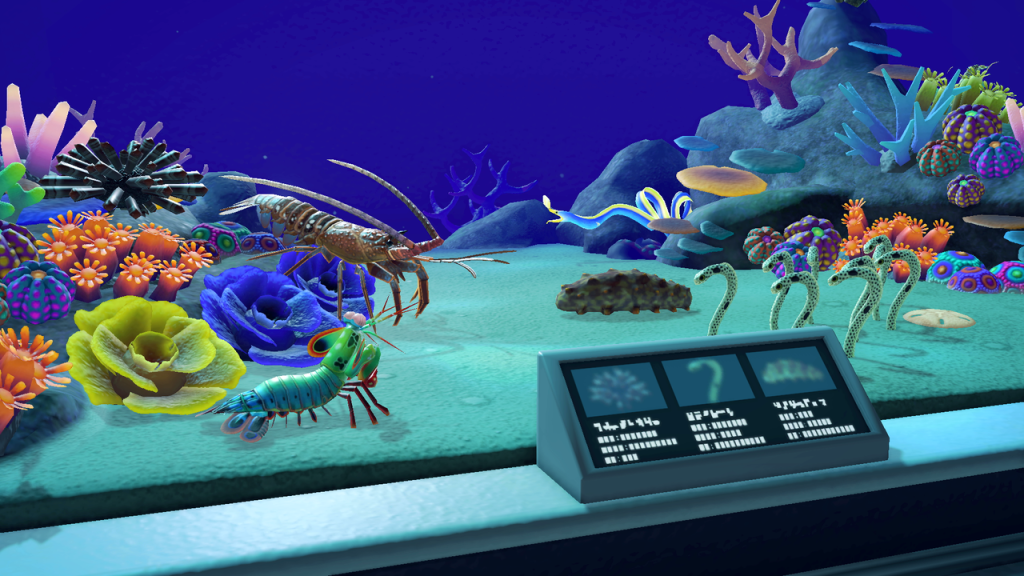

Collections

There are many types of collections, including the item sets of some MMORPGs that provide stronger bonuses or unique features if you manage to collect all of the items in a set. There are also collections where you have empty slots clearly displayed and your reward as a player is to fill those slots one by one.

Improvement

Sometimes, what you find isn’t a thing in itself but a means to make a thing you already have better. An improvement. This reward may allow you to choose what gets better, letting you specialise on something you enjoy doing, or lift something up that is lagging behind in your character build.

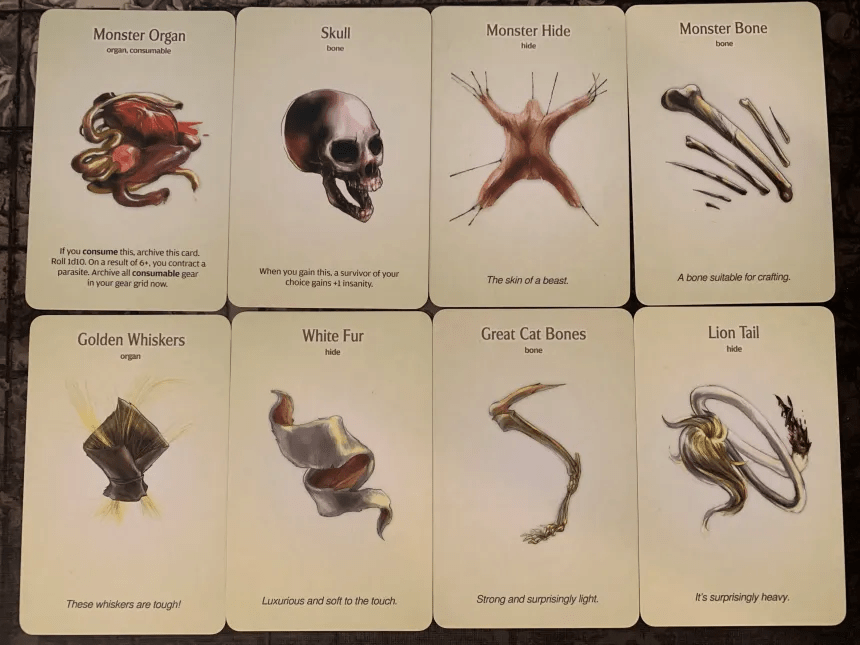

Reagents

In the Ultima games, you used reagents to learn new spells, so I’ll use the term here to represent any type of item collection that has no immediate use except as a smaller part of a larger puzzle. Once you manage to collect all of the reagents you need, you can make something from them.

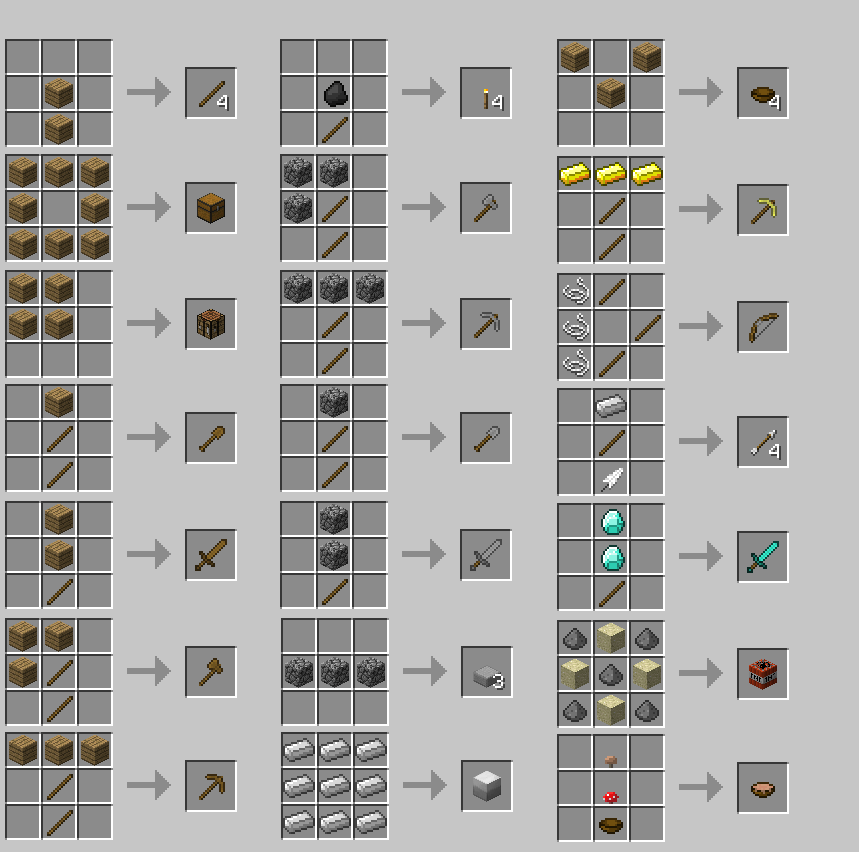

Early in Minecraft‘s history, you had to play the game and experiment to find the different shapes to craft different items. Today, you have a book of recipes included in the game. The first creates interesting exploration while the second provides goals to aim for while playing—both are ways to incentivise collection.

Flavor

Some rewards are for fun, as world-building, or provide other types of flavor. The many books and scrolls that you can read in the Elder Scrolls games are an example of this, since only specific ones are needed to finish the game’s quests. Flavor can be combined with other reward types, of course. But it can also be a reward on its own.

Cosmetics

Some items make no concrete difference on the game, have no playable effect at all, or have the same playable effect as other items. In many free-to-play games this is a popular model because it isn’t pay-to-win; and games with considerable content churn often rely heavily on cosmetics since it’s “just” art and usually doesn’t require any dedicated code support.

Handing out this type of reward is sometimes controversial, since it can feel for some players that they get less value. It’s also not cheap necessarily, for you as a developer, since you will still have to make the content before you can offer it and offering lots of cosmetic rewards has a sizeable overhead. But it is safe in terms of affecting your game’s balancing.

Sources

The next step is where to get all of these rewards. How they are awarded. We need some ways for the player to figure out the sources.

Containers

You open the chest, then grab what’s inside. Some games may have specific interactions or even require resources, like keys, to allow the opening of some containers. Others pepper containers all over the place.

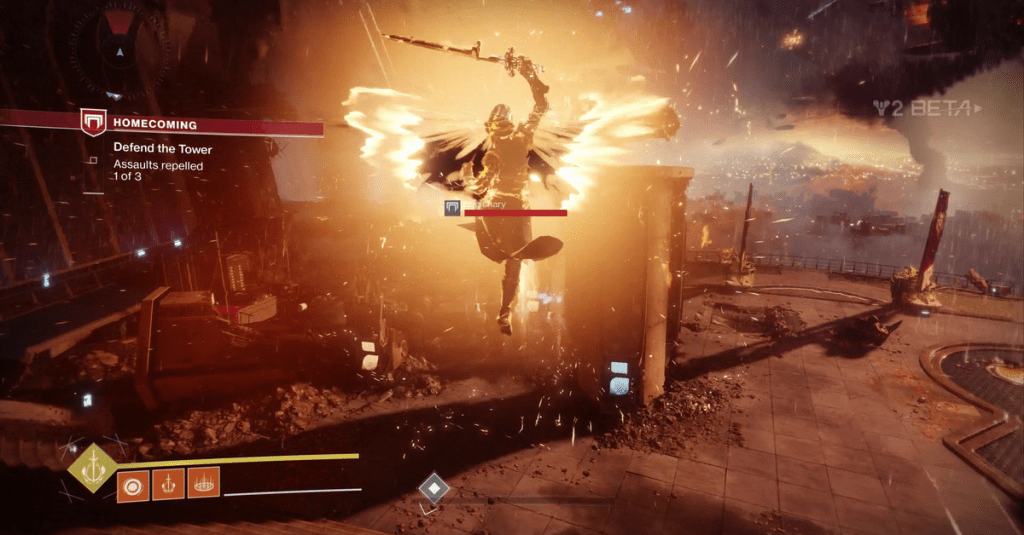

Piñatas

A piñata is a paper animal that you hit with a stick until it breaks and its candy stuffing falls out. In other words, it’s the exact same thing as enemies in games with loot. You hit them until their stuffing falls out. Think of it as a container with a health bar instead of an interaction prompt.

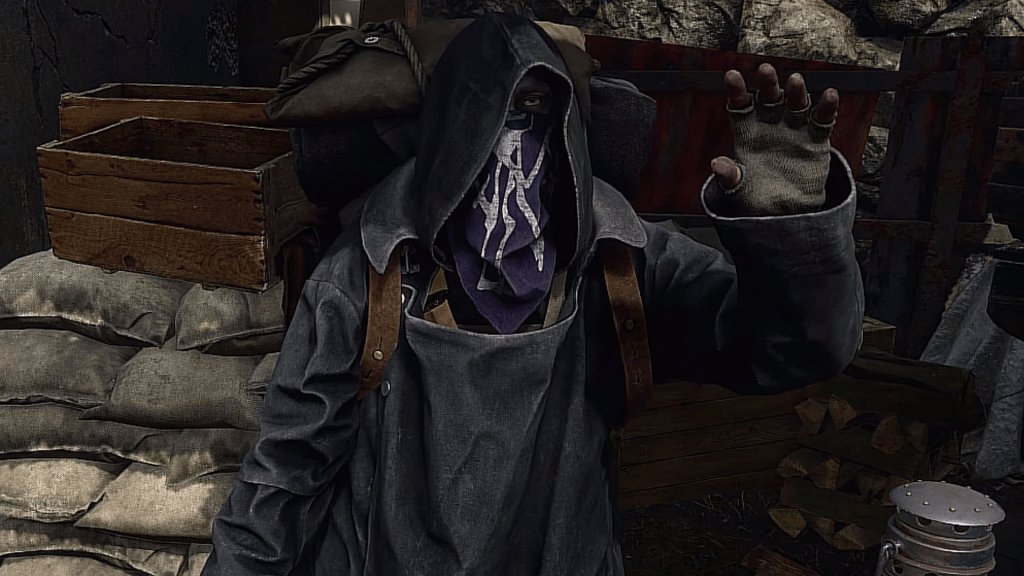

Vendors

Strictly speaking, a vendor is merely another type of container that also has a sink attached to it. They may charge you money for something, or require that you progress far enough in one of the game’s systems. Say, a reputation or quest requirement. The neat thing about them is that they can be upfront with what they are offering.

Quests

Thank you for liberating our village, adventurer. Here’s 25 Gold for your trouble. Also, feel free to peruse my shop. Health Potion? That’ll be 10,000 Gold. Completing quests is a very common way to get rewards, but games handle the rewards very differently. Some games give you their biggest rewards for completing “milestone” quests that wrap up whole stories. Maybe most prominently older Infinity Engine games, like the first two Baldur’s Gate games. Other games hardly give you anything.

It’s common in service games to lock specific types of rewards—like endgame currencies—to quests or missions of a specific type. You may have to do blacksmith quests to get iron, for example.

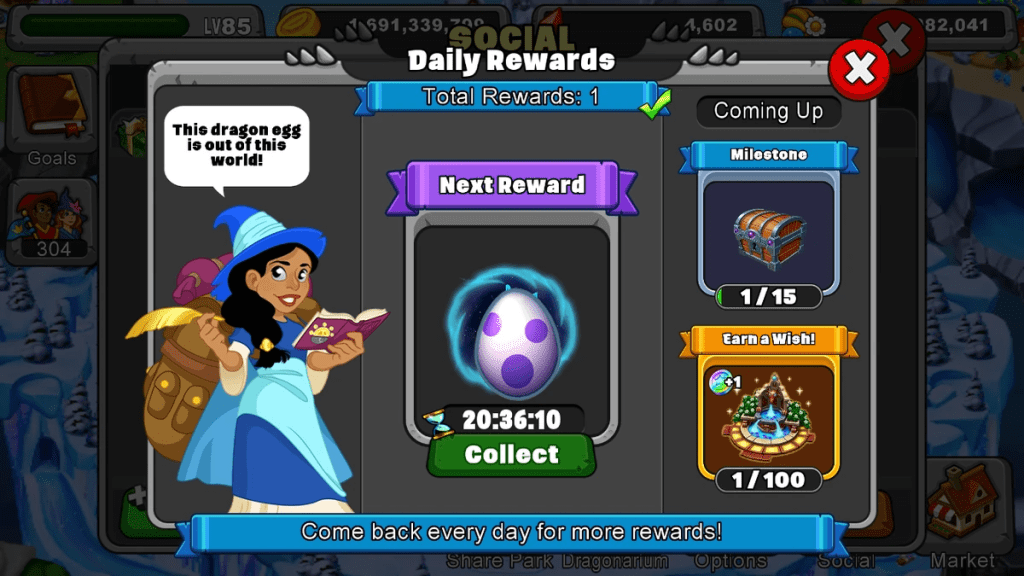

Scheduling

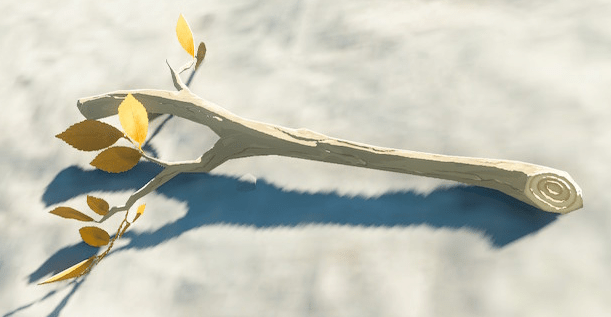

Welcome back! Here’s [500 Gold] and [Common Sharpened Stick] because we love you so much, dear [insert name here]. These types of sources are extremely common on mobile games and usually have a 30-day schedule, where each day beyond the 30th may continue handing out rewards but not of the same substance.

This format comes straight from 1-7-30 retention ideas. That you need to put extra effort into having players come back to your game after the first day, first week, and first month. This used to be an integral part of the strategy in early mobile game design but isn’t always part of it anymore since the life cycle can be much shorter now. But it’s there to create a kind of scheduling effect to get players to return to the game.

Ladders

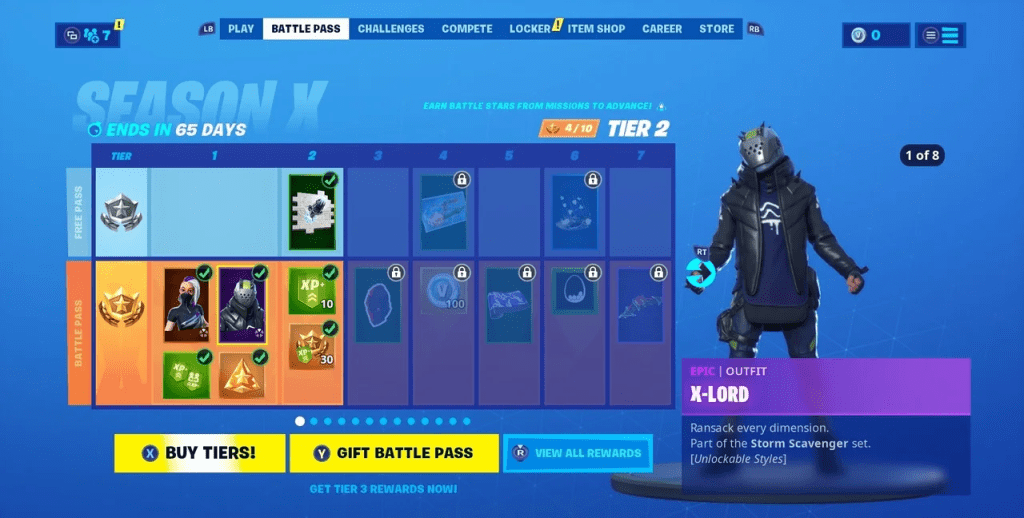

Another type of scheduling source is tied to in-game activities rather than time or to both at the same time, and can be likened to a ladder. This is functionally the same thing as unlocking things with level progression but has become tied more to external rewards and longer durations. Things like season passes and battle passes are examples of popular ladders.

A ladder can run for a limited time, be tied to your selection of character class, or something else. The important part of it is that it gives you something to strive for down the line. You can plan what activities to engage in to get there faster. There’s also often a monetary aspect where you can pay real money for faster progress or access to greater rewards.

Packs

Some games have had different kinds of packs for decades. Few Magic: The Gathering or Pokémon fans would get mad because you’re selling them packs of cards. Maybe most of all because the printing process is quite candid. You know that you will get 15 cards in a Magic booster and exactly how many of those cards will be rare, uncommon, or common.

In the digital space it gets trickier and easily gets much closer to gambling when players are able to spend real money on virtual items. This is a controversial space and for good reason. Because at the end of the day, that random stuff you’re paying money to get is already on the disk or in the download. It’s already embedded in your software. For a big box collector such as myself, this sale of stuff that’s already part of the game I paid for feels somewhat unnatural. Even unethical. But it’s definitely here to stay.

Gathering

One type of source that’s common in role-playing and survival games today is the concept of gathering. Picking flowers, collecting hides, bones, and all manner of natural resources that you can then transmute into something else using a recipe of some kind.

Gathering as an activity can be tedious, but is also one of those user patterns that feeds our primal hunter-gatherer instincts and can actually provide a brief sense of satisfaction even after hours upon hours of extended play.

Sinks

Any economy system in game design that only adds resources and never takes them away will generally run into one of three broad categories of problems:

- The player runs out of things to do,

- The value of the resources is diminished almost to uselessness, or

- Something they find is so good they don’t care about any other things after that.

The first often leads to the second. When you see that the players burn through everything at a rapid rate, you decrease the rewards, you increase the health numbers, and you introduce other types of friction to prevent the player from causing the first problem. This has a very high risk of making the game boring to play. A good reward system shouldn’t make it this obvious.

The third problem may happen in any game where what you get is tightly bound to how far you have progressed. Many other types of games suffer from this same effect. In almost every edition of Warhammer 40,000, for example, fans will complain that the most recent army book (called a Codex) is the coolest and weighs the balance towards the new kits players will now need to buy.

What you can do to decrease the chance of these problems is to add sinks of different kinds. Friction built into the design to drain your resources using different types of patterns or relationships to other resources.

Cost

You must spend some accumulated resource in order to make use of the reward. Can be to pay to identify the newly found magic item, or a cost in time to get to a specific location in an open world to have it properly unlocked.

Usage

Usage wears the thing down. This category includes ammo, durability, fuel, spell slots, and so on. But not consumables! Those are their own category of items. This is about having the active use of an item consuming the usage of that item over time, sometimes to the point that the item’s use is diminished, becomes useless, or even that the item is destroyed if you push it too far.

Cooldown

This amazing new thing you just received can only be used once every 30 seconds, hour, day, or week. Then it becomes inaccessible or its effect greatly diminished until that timer has run its course. This is largely an artifact of server latency and putting balancing ahead of immersion. More so than it’s good design. But it works, and it can definitely be the right solution for some types of games.

Diminished Returns

If every use of a reward is equal then use of the reward will usually stay linear. Diminished returns means that the first use will be powerful but that every subsequent use will provide slightly less. Imagine a gun that does full damage on the first shot, but then each shot after that does only 95% of the damage of the previous shot. Over time, shooting becomes almost completely useless. This pushes the player to shoot more in order to get the same effect, draining additional resources.

Conversion

You need three flawless gems and some gold to create one square gem, and then three of those to create one flawless square gem, and so on. Conversion sinks will generally use more of X to make fewer of Y, which is what makes it such an effective sink.

This serves two purposes:

- It funnels your early game items into the late game, by simply trashing the early game drops and pushing them forward.

- It always costs more than it gives, meaning that it’s an effective resource sink.

Progress Churn

Finding an amazing early game weapon means little once you’ve progressed further into the game and made it useless next to its higher-level equivalents. This may not feel like a sink, in reality, but it’s definitely a sink. As with all progress, it doesn’t have to be about resource sinks however but can also be about teaching the player how to play the game.

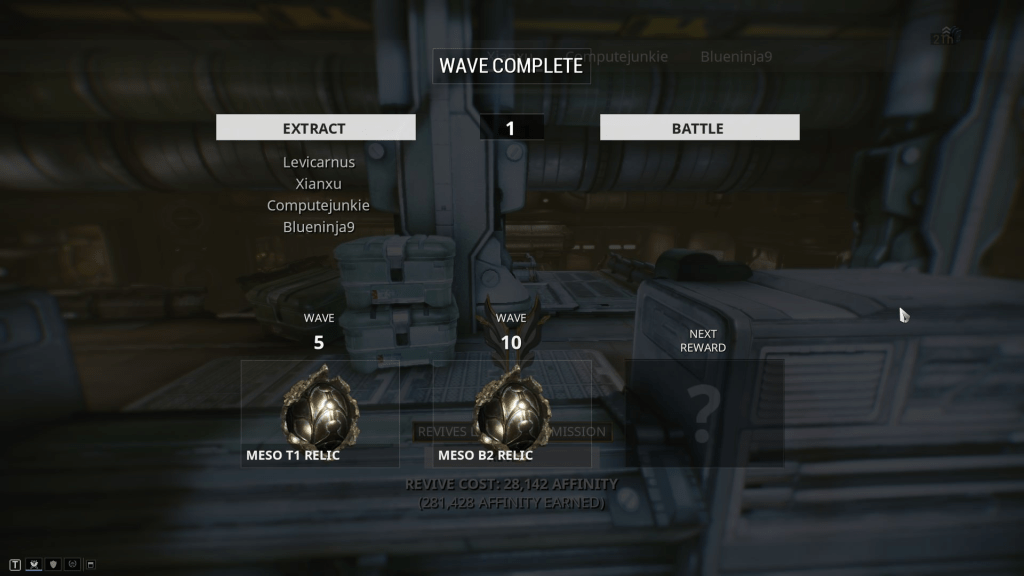

All or Nothing

In many games with multiple types of resources, such as free-to-play PvE giant Warframe, it can be valuable to play modes that lets you push further. Play just a little bit more to potentially get even bigger rewards. This sets the stage for a kind of game show situation, where you can choose to push on but will then risk losing everything. This is an amazing sink, since players will often overestimate their skills. But it also requires careful balancing, since it may also risk pushing them out entirely.

Rarity

Rarity is one of the most common ways to limit resource accumulation. It works in two ways. Firstly, it plugs directly into that Skinner-boxed variable-ratio reinforcement schedule we mentioned way back at the start. It may therefore make us want to play more. Second, trash items serves the purpose of making us want the cool items more. Finding all of those common things before we find our first rare one makes the dopamine high higher.

Seen as a sink, rarity means we don’t have to give you as much of the better stuff as we give you of the trash stuff. It means we can sit on the cool stuff for longer and therefore make sure that it doesn’t even enter the game loop in the first place.

Time

One common sink today is time. Making something time-limited and then removing it. This can be a season that runs for a couple of months, or it can be a booster that stays active for a minute. They’ve all been mentioned before, and they’re very common sinks because they can be arbitrarily added by us as developers to anything we feel like.

Consumables

You can also consume the rewards on use. They are your health or mana potions, magical scrolls, hand grenades, and other one-time effects. Once used, the consumable is gone. It means you need to hoard whole stacks of them to retain access to whatever it is they unlock.

Consumables may have one-time effects, like the Town Portal in the image. They can also be boosters, for example doubling your XP for 24 hours, and so on. They can really be almost anything as long as they are spent on use.

Conclusions

What’s good about listing things like this is that you can start thinking about ways to hybridise them and to mix and match things for your specific game. How about a system that awards boosters via containers and has currency that grows over time but must be paid to unlock seasonal rewards? The sky is the limit.

It’s not uncommon for some card games to treat their primary feature drops, the cards, as both set collections and reagents, for example. Collect up to four of the same card and then combine multiples of the same card into upgraded versions of itself. Rage of Bahamut is an example of this.

There are probably many things we haven’t discovered yet when it comes to rewards, and I would love to hear what you come up with in your own designs!

Never hesitate to throw me an e-mail at annander@gmail.com if you want to share such designs, or just tell me how wrong I am in general. The latter is something the Internet seems quite fond of.

3 thoughts on “Gamification, Part 3: Loot”