The What and The How

Hey there, I’m Keelan.

For the better part of my career in the games industry I’ve worked as what’s known as a Game Economy Designer. Game Economy Design predominantly concerns itself with the relationship that the resources within your game have with the mechanics of your game. If this sounds like a very nebulous definition, it’s because game economy design (and really, economics) is perhaps better thought of as a lens through which to understand your game than anything else.

Still, I want to do more than wax philosophical about the nature of high-minded economic principles like utility and feedback loops. Yes, there will be some of that in this blog post, if only because I think it’s important to understand the abstract concepts before getting our hands dirty, but rest assured that I’ll be demonstrating some of the tools and methods I use to perform Game Economy Design. These tools and methods help us to measure and balance the distribution of resources within our game by taking a number of key economic concepts into account:

- Transference of Resources – The function of one or more units becoming another. Quantifying Damage per Second and other factors helps us understand Time-to-Kill which alongside XP-per-Kill and XP-per-Level tells us Time-to-Level.

- Utility – Involves attempting to find a universal measurement of value within our game that we can attribute to all resources. Perhaps, like me, you’re a fan of League of Legends (a fascinating game for studying feedback loops, an awful game for hair retention). If so, you may have come across the term “gold efficiency” when observing high level players comparing one item to another. In essence, these players are normalizing the stat-per-gold across each item in the game to determine which items give them the most stats for the gold invested; which items provide the best utility.

- Relative Strength of Feedback Loops – Involves understanding how and why transference may change over time. For instance, different aspects of our design may decrease Time-to-Kill during our mid-game. Perhaps Enemy health and player stats increase linearly within our game, but we introduce combat synergies over time that increase the influence of player stats on damage output. How might this impact Time-to-Level? What about the transference of other resources within our game, such as the gold income per hour?

If it’s true what Frank Lantz, Director of NYU Game Center wrote, that “Games are basically operas made out of bridges”, then Game Economy Design concerns itself with the tempo of the music and the points of slack and tension among the bridges.

So, what do Game Economy Designers measure and how do they measure it? Let’s discuss.

The What

System Flows and Points of Interaction

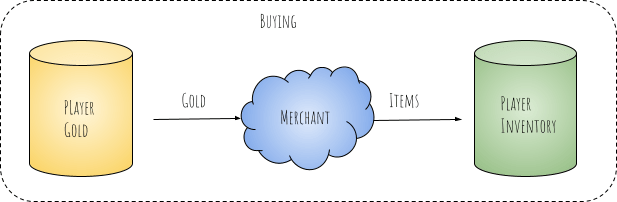

Systems flows describe the directionality of resource exchange such as from gold to weapons when you buy an item in a merchant system, whereas points of interactions describe the act of buying and selling.

System flows and points of interaction can range from simple to complex depending on the scale of the system (consider that a collection of systems is also a system) and on the kind of player experience we want to create.

On the one hand, we may want to tie player progress to a number of interdependent systems with varying complexity such as items, upgrades, player stats, level ups and skill trees. On the other hand, we may prefer taking a more straightforward approach to system interactivity in a purchase flow – a player doesn’t want to jump through hoops to enjoy something they’ve spent money on (or do they? See: Battle Passes).

Common components of system flows in games include the following*:

- Conditional Constraints – requirements that gate access to systems or content until specific conditions are met such as player levels, crafting requirements, or story milestones.

- Variance (RNG) – ways in which we generate different outcomes from the same input– think randomly rolled loot tables in treasure chests, random encounters, or randomly assigned modifiers on a crafted item.

- Efficiency Modifiers – Things that impact the strength of the system flow, on which the system is dependent. The impact of player level, inventory, and skill tree allocation on damage output, for instance.

*but are limited by my desire to voluntarily express them in a spreadsheet.

Progression Curves

Progression curves are the mathematical models governing how our gameplay experience changes over time. How many experience points should a player need for each level up? How much damage should a player do over time? How should enemy HP grow over time?

This is where some level of algebra is helpful as we’ll be defining these curves as pen-meets-paper (or data-meets-spreadsheet). Some of my favorites include:

- Linear Progression – Perhaps the most trustworthy of all progression curves. The same input always yields the same output. This is useful for systems that you want to build your experience around– perhaps you want players to start your game struggling to defeat a single enemy and but eventually be mowing down hordes of enemies- assign a linear progression curve to enemy HP and then get wild with the progression curves on your various damage-generating systems.

- Exponential and Logarithmic Progression – USE THESE WITH CAUTION. Exponential Progression Curves have a tendency to invalidate designs and wreck ecosystems over time. Exponential Curves do this by rapidly increasing the output for each unit of input and Logarithmic Curves do this by rapidly reducing the output for each unit of input. These become a lot easier to manage when we apply fractional modifiers to the curve or when our systems have definitive endpoints, such as a maximum Player Level.

- Sigmoid Curve – Also known as the “S-curve”. I’ve got to be honest, I haven’t found a great application for a Sigmoid Curve in a single system, but I think it’s a great curve for demonstrating a player journey. For instance, a player’s power progression journey in an ARPG might look like several Sigmoid Curves in a trench coat.

Utility Functions

Utility describes how much we value something, ideally in a way that we can compare against other things. While the economic concept of utility is fascinating to discuss in the abstract (consider the myriad of factors that determines how much value we place on a bottle of water – time, place, and presentation to name a few), mathematically representing utility in economics is quite the headache. Luckily for us, we’re measuring the economy of a game and not that of say… the consumer car market.

When it comes to measuring utility within our game, we might be happy enough to look at transference rate within a system. From a game balance perspective, we may look at the amount of stats provided relative to the gold cost of our weapons. However, in the interest of better understanding the player perspective we might alternatively be interested in knowing the number of enemies a player must defeat to afford the weapon.

Even better, we could try to understand the time-investment (“farm”) required for the player to defeat those enemies and acquire that weapon. Once we’ve arrived at a metric of time, we’re truly thinking about our game from a game economy perspective because ‘time’ is a universal resource that governs much of the player experience.

Another common ‘universal resource’ that governs the player experience is money. While it doesn’t necessarily explain why one store bundle performs better than another, it does at least partially explain why more players buy Battle Passes than store bundles. Battle Passes typically contain the equivalent of multiple store bundles in terms of content for a fraction of the price.

Feedback Loops

This is where things get fun. By manipulating the way our various progression curves interact with one another, we can change the nature of feedback loops in our game. We can speed up the income rate of one or more resources or slow them down. This allows us to manage the frequency and intensity of challenge, reward and relief within our game over time.

Feedback Loops are most easily identified in Player Data when we can observe cause and effect in a (hopefully) large sample size. However, the job of identifying them in Player Data is made substantially easier when we’ve first set about attempting to identify them in simulations and before that, in models. By dictating our expectations about the nature of the interconnections between our systems in models, and attempting to observe them in our simulations, we build the muscle memory necessary to observe them in player data.

The How

TL;DR: Spreadsheets containing system inputs, models that represent the behavior of those systems over time, and simulations that inform the behavior of the system.

Diagrams (or visual models)

Diagrams are important not only for refining our own understanding of a system, but also for communicating that understanding to others. The most common uses for diagrams in Game Economy Design are economic flow diagrams, where we map out system flow and points of interaction.

Here’s what that might look like in a simple merchant system:

But you could describe a more complex system as well:

Mathematical Models

Models are our way of representing how we intend for our gameplay experience to change over time. These are foundational to Game Economy Design. Not only are they used to concretely balance progression curves within systems, but they are also used to balance larger abstract design intents within the player experience.

For instance, we may use a model to define specifically how many experience points are required at each player level but we may also use a model to define our design intent for the transference of time-to-levels, or how much time our player should spend accruing those experience points in order to reach some level. The latter example is abstract because every player will play our game differently, but we can temper our game balance using simulations that dictate the conditions under which we achieve our design intent.

Simulations

Simulations are where we make assumptions about how our players will behave within our game and then use those assumptions along with our defined system parameters to determine whether or not the balance of our systems, when experienced by our assumed player behaviors, achieve the intent of our systems.

We may have a model that indicates a time-to-level based on enemy health data and player damage estimates. However, for the sake of testing our system, we might assume that we have a ‘more skilled player’ which achieves player damage 20% higher than our estimates and a ‘less skilled player’ which achieves player damage 20% lower than our estimates. We could then “simulate”* the difference in the time it takes for these two player types to complete our game or other relevant aspects of our design goals.

Additionally, as more players play our game, we’re able to get a better understanding of how different players will experience our game and use that knowledge to refine our assumptions. We may discover that players can be significantly more skilled than simply achieving 20% higher damage, or significantly less skilled than simply 20% less. These observations will yield more accurate simulations, which in turn will result in a more informed game balance. This is where player data comes in.

*Note: I’m using simulate in quotations here because this example is a fairly obscene over-simplification. If there’s enough interest, I’ll write up something more in-depth about this fairly under-utilized design practice.

Player Data

Player Data allows us to observe how our game is experienced in the wild, as opposed to how we believe the game will be experienced in our models and simulations or how we experience it as the developers. This is where we can finally see how close our design intent is to the real player experience.

Using this information, we can rebalance our systems to better achieve their intent – both individual systems and the game as a whole. Our more abstract models, those that combine multiple systems, are especially likely to benefit from Player Data as the interconnections between the systems will become more apparent.

For example, we may discover that our model for time-to-level presumed that a player would have acquired a weapon at level 2 only to realize that a poorly balanced gold economy prevented players from acquiring one until much later than we intended, significantly impacting early progression within our game.

Concluding Remarks

So there you have it, Game Economy Design in a nutshell. I genuinely hope that if you’re reading this, you’ve found it more than informative; I hope you’ve found it useful. If not, please reach out and voice your (hopefully well-worded) criticism. After all, much like Game Economy Design – really much like everything – this only gets better through critique and iteration. The diagrams, models, and simulations we make are always only our current best understanding of our designs, and we designers are typically in a constant struggle of improving our understanding of our designs as they change and evolve (roadmap and documentation be damned). These might represent the toolbox for game economy design, but the real “How” is communication and iteration.

Do the work, show it to your team, be open to criticism, then do it again and again until it’s polished – that’s the real how.

Until next time,

Keelan

One thought on “Game Economy Design”